![]()

A TO Z ENCYCLOPEDIA

ABLE-BODIED

(See: Classification; Deserving and Undeserving Poor; Dietary Class; House of Correction; Labour Test; Work)

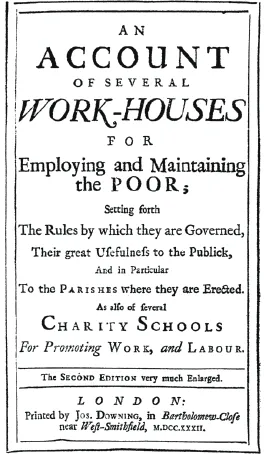

ACCOUNT OF SEVERAL WORKHOUSES

An Account of Several Workhouses for Employing and Maintaining the Poor was first published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in 1725. The book espoused the use of workhouses and charity schools and detailed the setting up and management of more than forty local workhouses then in operation, especially noting the financial benefits that could result from their use. The book was strongly influenced by the activities of the workhouse entrepreneur, Matthew Marryott. The success of the publication led to a second enlarged edition in 1732.

(See also: Marryott, Matthew; Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK))

ADMISSION TO A WORKHOUSE

(See: Entering a Workhouse)

ADDRESSES

The cover of the 1732 edition of An Account of Several Work-houses – the first workhouse directory.

In 1904, the Registrar General advised local registration officers in England and Wales that where a child was born in a workhouse, there need be no longer any indication of this on the birth certificate. Instead, the place of birth could be recorded as a euphemistic street address. For example, births at Liverpool Workhouse were thereafter recorded as having taken place at 144A Brownlow Hill even though no such street address actually existed. Similarly, Nottingham workhouse used an address of 700 Hucknall Road for this purpose, while Pontefract workhouse delighted in the pseudonym of 1 Paradise Gardens. Some unions, particularly in smaller towns, invented a new name for their workhouse. The Trowbridge and Melksham workhouse thus became Semington Lodge, Melksham. Where a workhouse was located on a road such as Workhouse Lane, a renaming of the thoroughfare was sometimes carried out.

The same practice was adopted from around 1918 for the death certificates of those who died in a workhouse. It was not until 1921 that Scotland followed a similar course and recorded what were referred to as ‘substitute’ addresses for births and deaths taking place in a poorhouse.

The directory of poor law institutions in England and Wales (Appendix E) includes details of many of the euphemistic addresses adopted by workhouses.

AFTERCARE

The aftercare of young people leaving the workhouse to enter service or an apprenticeship became an increasing concern during the mid-nineteenth century. Following the 1851 Poor Law (Apprentices etc.) Act, union relieving officers were required to visit those under still under sixteen at least twice a year and ensure that they were being properly fed and not mistreated.

Following her appointment as the first female Poor Law Inspector in 1873, Jane Senior (often referred to as Mrs Nassau Senior) took a particular interest in matters concerning children, especially the education of girls. She also championed use of the cottage homes system. At her premature retirement due to ill-health in 1874, she outlined proposals for the creation of a national scheme for the aftercare of0 pauper girls leaving the workhouse, especially those aged of sixteen or more. Her ideas, taken up by Henrietta Barnett, led to the formation of the Metropolitan Association for Befriending Young Servants (MABYS). By the 1890s, the Association had more than 1,000 volunteers who visited girls at their workplaces, and helped them find accommodation and new employment, until they reached the age of twenty. MABYS and similar charitable organisations were helped by legislation in 1879 which allowed poor law authorities to contribute to their funds.

From 1882, the Local Government Board included a report from MABYS in its own annual report. During 1893, the Association had under its supervision 2,412 girls from Poor Law Schools and 955 from other institutions. Of the total, 1,700 were reported as ‘satisfactory in their conduct and work’, 740 as ‘those against whom no serious faults have been alleged’, 189 as ‘accused of dishonesty, untruth, extreme violence of temper etc.’, and thirty-two as ‘having lost character or been in prison for theft etc.’2

After the First World War, MABYS was renamed the Mabys Association for the Care of Young Girls. It continued in existence until 1943 when its activities were taken over by the London County Council.

The Association for Befriending Boys was formed in 1898 and performed undertook similar activities to MABYS within the metropolitan area. Outside London, a similar role to MABYS was performed by the Girls’ Friendly Society (GFS), established by the Church of England in 1875 and still in existence. The Society provided reports to Boards of Guardians on girls up to the age of twenty-one and also operated Homes of Rest and Lodges for girls who were unemployed. Unlike its London counterpart, the GFS limited its work to ‘respectable’ girls.

ALCOHOL

One of the most common rules applying to workhouse inmates was a general prohibition on alcoholic beverages, at least in the form of spirits, unless prescribed for medical purposes. Restrictions on other forms of alcohol, especially beer, varied at different periods in history.

The Parish Workhouse

At the Croydon workhouse, opened in 1727, the rules forbade any ‘Distilled Liquors to come into the House’ – a restriction perhaps aimed at the new habit of gin-drinking which was sweeping England at around this time.3 At Hitchin workhouse, in 1724, it was reported that a lack of tobacco and gin was causing many inmates to ‘get out as soon as they can’.4 Brandy, too, appears to have been in a similar situation. Some of the parish poor at St Mary Whitechapel rejected the offer of the workhouse and ‘chose to struggle with their Necessities, and to continue in a starving Condition, with the Liberty of haunting the Brandy-Shops, and such like Houses, rather than submit to live regularly in Plenty.’5

A century later, the 1832 Royal Commission investigating the operation of the poor laws, was told by the overseers for the London parish of St Sepulchre that intemperance was a major cause of pauperism: ‘After relief has been received at our board, a great many of them proceed with the money to the palaces of gin shops, which abound in the neighbourhood.’6

Although the imbibing of spirits by workhouse inmates was usually prohibited, items such as wine, brandy and rum were often prescribed for medicinal purposes because of their supposed stimulant properties. The accounts for the Bristol workhouse in 1787 record the expenditure of £2 19s 7½d on ‘wine, brandy, and ale for the sick’. At the Lincoln workhouse, in the winter of 1799–1800, colds and other ailments were so prevalent that the Clerk was instructed by the Board to purchase two gallons of rum ‘for the use of the House’. Surprisingly, gin still occasionally features in workhouse expenditure – the 1833 accounts for the Abingdon parish workhouse include an entry for two pints of gin, although the precise use to which this was to be put is not revealed.7

Beer

One form of alcohol that was usually allowed to parish workhouse inmates was beer, something which at that time formed part of most people’s everyday diet. Apart the attractions of its flavour, beer could provide a safe alternative in localities where the water supply was of dubious quality. Beer came in two main forms, strong ale and half-strength ‘small’ beer, the latter being a standard accompaniment for meals, often for children as well as adults.

Workhouse inmates sometimes had a fixed daily beer allowance such as the two pint quota imposed at the Whitechapel workhouse in 1725.8 At other establishments it was available ‘without limitation’ as happened at the Barking workhouse and also at the Greycoat Hospital in Westminster, an institution purely for children.9

As well as being provided at meal-times, extra rations of beer were often given to those engaged in heavy labour such as agricultural work. At one time, female inmates working in the laundry at the Blything Incorporation’s House of Industry at Bulcamp in Suffolk were each allowed a daily ration of eight pints.10

Many workhouses brewed their on beer on-site and their brewhouses contained all the paraphernalia associated with beer-making. In 1859, when the contents of the old Oxford Incorporation workhouse were sold off, the auctioneer’s catalogue entry for the brewhouse listed the following items:

Mash tub, underback, four brewing tubs, five coolers, five buckets, skip, tun bowl, tap tub, bushel, spout, malt mill, copper strainer, two pumps, brewing copper, three square coolers, with supports, spout, &c. Large working tub, two others, beer stands, three lanterns, &c., three casks, and strainer.

Alcohol in Union Workhouses

In post-1834 union workhouse, the consumption of alcohol – including beer – was generally prohibited except for sacramental purposes such as the taking of Holy Communion, or for medicinal use when ordered by the workhouse medical officer. A further exception was added in 1848, when it was allowed to be provided as a treat on Christmas Day.

As well as these general exceptions, some union workhouses revived the old practice of providing beer to able-bodied inmates engaged in certain types of heavy labour. In 1886 the Wirral Union was allowed by the Local Government Board to provide extra food and ‘fermented liquor’ to paupers employed in harvest work on land belonging to the guardians. In 1903, when an auditor surcharged a workhouse master for allowing beer to able-bodied inmates without such approval, the strange response came that if such an allowance were not made, ‘some of the paupers would leave the workhouse.’11

The consumption of alcohol, like virtually every other activity that took pl...