![]()

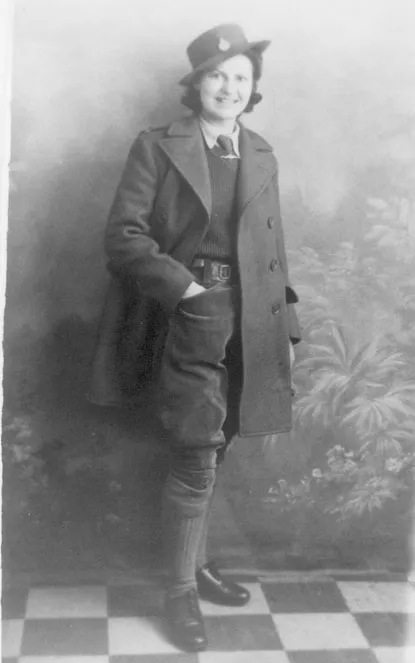

Baggy Brown Brown Breeches And A Cowboy Hat was the title of one Land Girl’s book containing her reminiscences. Despite this description the ‘Walking Out’ uniform could be very smart, even if some of it had to be ‘home tailored’, and the hat bent to suit the personality of the wearer!

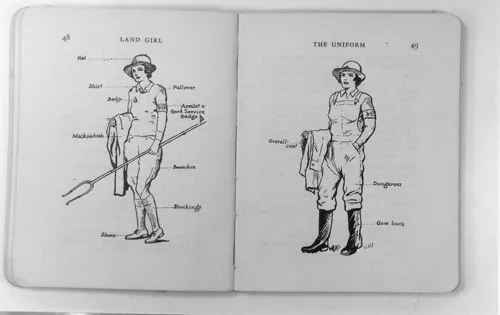

Laced brown brogue shoes were worn with brown corduroy (or occasionally gabardine) breeches, and fawn knee-length woollen socks. A smart green V-necked long-sleeved ribbed pullover was worn over a fawn short-sleeved Aertex shirt, with the WLA tie added for formal wear. The uniform was topped with the brown felt ‘pork-pie’-style hat, with the WLA badge on the band. This uniform was completed by a good quality melton three-quarter length brown overcoat that was both warm and rainproof (at least until it got wet right through!). For parades and rallies the WLA armband was also worn on the left arm. The colour reflected each five years of service, and apart from the WLA and a crown woven into the cloth, the girls sewed on half diamond cloth badges for each six months of service.

The working uniform of brown dungarees with matching jacket had to serve for most of the work. Wellington boots were issued when available, and some girls received leather ankle boots. Extremes of hot, cold and inclement weather led to many unofficial variations of the uniform. The range varied from the adaptation of dungarees into shorts (some were very short!) during the hot summers, to outer layers of old sacks tied round with binder twine during the worst of the winter rain.

The official uniform as issued to most Land Girls, 1939–50. This illustration is from Land Girl, by W.E. Shewell-Cooper, a manual for volunteers published in 1941, price 1s.

Miss Margery Kent poses for a photograph in her ‘best’ uniform shortly after it was issued. The photo was taken at Sutton in Surrey, 28 December 1942.

A party of Land Girls wear their best uniform on a visit to Maidstone Zoo in 1943. The day out was organized by the local officer for girls working in the area. Pat Ware (née Taylor), on the right wearing a hat, worked for Mr John Berridge, a Covent Garden Market stallholder who grew vegetables for sale in London on land requisitioned by the Kent War Agriculture Executive Committee.

Betty Merrett (née Long) wears gum boots with her uniform for tractor driving, 1944. The tractor is a Fordson Standard model ‘N’. The boots were often in short supply owing to the wartime restriction on rubber.

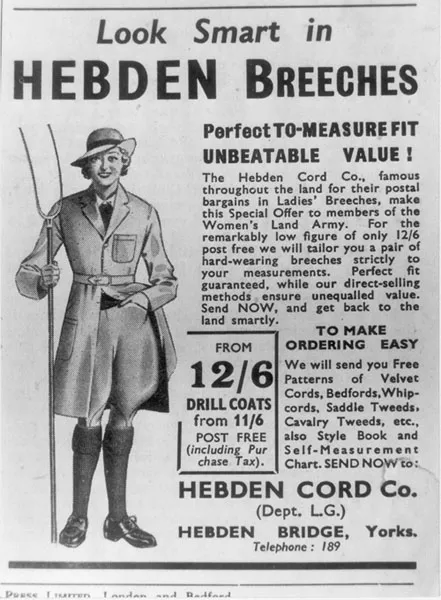

The Land Girl magazine, published monthly, carried this advertisement in many of its issues. This example dates from February 1941. Those who could afford them were able to order more flatteringly cut breeches than the official baggy versions.

A group of market gardening Land Girls at Manor Fruit Farm, near Normandy in Surrey, showing the issued working overalls. The girls called them dungarees. The addition of the leather belt was adopted by most but not all girls. Left to right: Doreen Puttock, Iris Mais, Marjorie ?, Ruth Lamdin, Kathleen Reigate, Renée Middleton (née Abbott).

‘Mollie and Beryl’ show the working uniform, with and without the overall jacket. Mollie Sivyer is on the left.

Eileen Mitchell (née Vile) is ready for work accompanied by her junior assistant Joan Geall (the farmer’s daughter) at Lower Hill Farm, Pulborough, Sussex, 14 April 1945. The little girl’s uniform had been made by her older sister from one of Eileen’s worn-out overalls. The hat was genuine and Eileen’s.

Hot weather produced quick alterations to the overalls. The ground must still have been muddy as shown by their wearing turned-down gum boots, but the chorus line looks very happy in spite of it. This was a hoeing gang from the hostel at Dyke Road, Brighton, enjoying a break while working on potatoes on War Agricultural Committee land on the South Downs at Saltdean, 1948. Jean Stemp (née Ellis), known as ‘Ginger’, is second from the right.

![]()

TWO

HOSTELS & BILLETS

Many of the Land Girls were placed in lodgings and billets near their place of work. These could be cottages in an adjacent village, with the families of fellow farm workers, or living in the farmhouse with the farmer and his wife. Many billets were pleasant, but some varied from poor to atrocious.

Few of the cottages boasted baths or readily available hot water for washing, and the bedding provided was none too clean. A few landladies took rations intended for the Land Girls to add to the meals of their own families, giving the girls small portions and the poorer quality food. Occasionally girls living-in with the farmer and his family were treated as though they were household servants as well as farm workers.

A good and efficient Land Army local representative with the welfare of her girls at heart could often sort out these difficulties by a word in the right place, or moving a girl to another billet. However, it was not unknown for the local representative to be on familiar terms with the farmer or cottager in her area, and so to take their part in disputes.

When the girls settled down and found their feet they could often find alternative billets for themselves. Nevertheless, the feelings of these young girls, often moving from home in towns and cities for the first time in their lives, and being pitched into this rural environment, can be imagined.

As the numbers of Land Girls increased and mobile gangs were formed for labour-intensive work, hostels were opened to accommodate girls in available vacant country houses and schools. The numbers accommodated at each hostel could be as low as six, or up to a hundred girls. Once the initial problems were overcome most provided an acceptable standard of food and accommodation, but the comfort...