![]()

1

POWER GAMES

During the Late Iron Age, a mere 2,000 years ago, food production, social organisation and human settlement patterns were not ‘primitive’ but were rather modern in outlook. Land was being intensively farmed, surplus coming under the control of an increasingly affluent and largely non-productive aristocracy. A sustainable surplus meant that it was possible for the elite and their followers to purchase foreign luxuries, fund works of art, garner political support and build military muscle, an important consideration when competing for natural resources. Human settlement was, in the British Iron Age, becoming more centralised; tribal territories were expanding; social spaces becoming more strongly defined.

All this was happening at a time when Western Europe was undergoing a period of significant change: Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and now France and Germany having fallen under the dominion of a militaristic monarchy. Millions had died or been enslaved in the process of conquest and assimilation. The battle for Britain was shortly to begin.

FIRST CONTACT

Britain was viewed as a natural target by the power-hungry Roman general Julius Caesar. By 55 BC, Caesar had subjugated much of Gaul and led troops on a punitive campaign across the Rhine into Germania Magna. In 55 and 54 BC he led invasions into Britain, not, it would appear in order to form the basis of permanent conquest, but in order to capture the Roman public imagination; he wanted to demonstrate his ability to go anywhere and do anything.

Truth be told, the expedition of 55 BC was not a great success, at least in military terms. Trapped on the beach, hemmed in on all sides by the enemy, Caesar could only watch helplessly as his cavalry reinforcements were scattered in a storm at sea, whilst his own transport vessels were dashed to pieces on the shore. A stalemate ensued, the Britons being unable either to eliminate the Romans or dislodge them from their coastal base. The Romans, on the other hand, found themselves unable to break out of the beach positions and attack British targets. Eventually both sides called for peace and the Roman army left in a fleet of hastily repaired ships. Characteristically, Caesar, in his own work the Gallic Wars, makes even this sound like a victory.

Within a year of departing, the Romans were back. This time Caesar hoped to obtain a more impressive result: ideally defeating the Britons in battle, capturing a British town (or two) and the acquisition of slaves and booty. Unfortunately for him, the British tribes presented a combined face, electing one of their own, a man called Cassivellaunos, as supreme leader. Although we know nothing about Cassivellaunos, his significance cannot be overstated: he is the first character to emerge from over half a million years of British prehistory; our first identifiable Briton. Caesar portrays him as the villain of the piece, previously intimidating his neighbours by fighting expansionist wars of territorial acquisition across southern England. In the Roman mind, Cassivellaunos was a destabilising influence: his very existence legitimising Roman military activity. Caesar, ever aware of an opportunity for political gain, could claim that armed intervention in Britain was necessary in order to force regime-change, weeding out dangerous warlike elements and bringing peace to the northern frontier of the Empire.

The other British aristocrat that Caesar acknowledges during his campaign of 54 BC was Mandubracius of the Trinobantes (or Trinovantes). The importance of this particular character is that he represents the first Briton to embrace ‘the protection of Caesar’, a wonderful euphemism. Mandubracius’ people seem to have previously fought against (and been defeated by) Cassivellaunos and therefore viewed Caesar as the lesser of two evils. That any deeply held blood feud or clan enmity would at some point destabilise Cassivellaunos’ resistance to Caesar must have always been a risk. Given his history, it was likely that certain groups would view the arrival of Caesar as the perfect opportunity to level old scores and destroy a more ancient foe. Whilst Caesar was weak, his troops unable to find food or safe haven, then Cassivellaunos might just succeed. If Caesar looked strong, however, then former inter-tribal enmities could reopen and the Briton’s position as warleader of a unified resistance would effectively be undermined. Cassivellaunos’ ultimate failure says more about the politics, squabbles and inter-ethnic tensions of tribal groups in southern Britain than anything else.

At the end of the brief campaign of 54 BC, Caesar left taking a number of British hostages with him. Hostages were traditionally taken by Rome as a way of ensuring the loyalty of conquered peoples. If the children of a defeated monarch were retained in Roman custody, then their parents would be less likely to revolt. Hostage taking also had a more significant aspect to it, however, for, having been taken from their homes, the children of native aristocrats would be brought up within the Roman world and gradually indoctrinated into the Roman mindset. If such Midwich Cuckoos were ever required to return to their people, they would take back a range of new gods, ideas, customs and language: Latin. Having been exposed to a Mediterranean lifestyle from a very early age, they could help fast-track Roman culture within and among the aristocratic classes of their own people.

As well as hostages, Caesar took with him promises of protection money (which he termed ‘tribute’) and assurances that Cassivellaunos’ tribe would ‘not wage war against Mandubracius nor the Trinobantes’. Mandubracius was left as a British ally of the Roman State and his tribe as a ‘Protectorate’. This Briton was someone who, from now on, would enjoy special trade status and enhanced power. He could, in theory, also rely on Caesar or his nominated officers to provide military assistance in times of trouble. The concept of allied or client kings and queens was one which Rome found particularly favourable, for they provided the State with a degree of security along potentially unstable frontiers. From an economic perspective, client kingdoms also provided Rome with the opportunity to make significant amounts of money through increased trade.

IN CONTROL

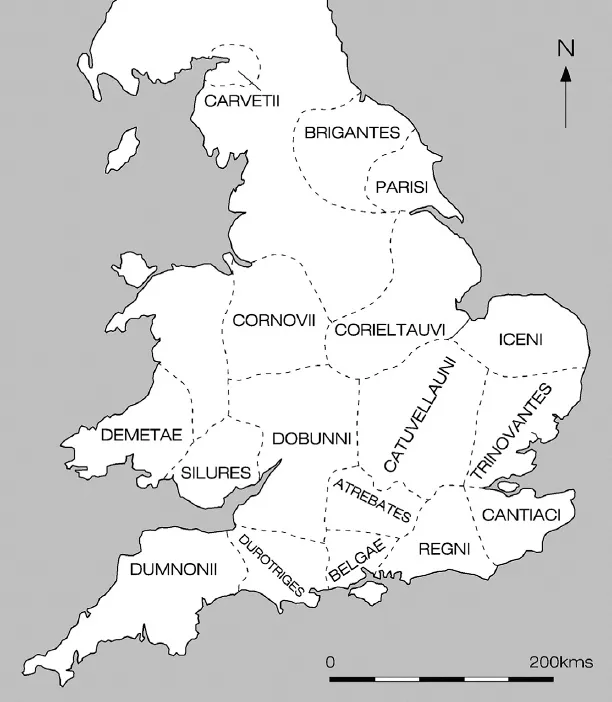

A sense of what life was like in Iron Age Britain, at least in political terms, is difficult to achieve. Plans and maps depicting ‘Life in the Iron Age’ can today create a wholly artificial sense of reality. Sites and artefacts appear in clusters, neatly grouped into discrete tribal zones (Image 7). Each tribe has a name and possesses, at least on paper, clearly defined borders. Each tribe evidently had its own leaders but we do not know whether such leadership was in any way stable nor whether it brought a sense of unity and identity to the population at large.

7. The traditional view of the major Iron Age tribal groupings within the area that was to become the province of Britannia. (Courtesy of Jane Russell)

Contemporary Roman and Greek authors are of little help, as most simply reinforce the perspectives and prejudices of their own times, depicting the Britons as barbaric and rather backward. ‘They are simple in their habits,’ Diodorus Siculus tells us from the late first century BC, ‘and far removed from the cunning and vice of modern man. Their way of life is frugal and far different from the luxury engendered by wealth.’ ‘The Britons,’ Tacitus, writing in the early second century AD, tells us, ‘were formerly governed by kings, but at present they are divided in factions and parties among their chiefs; and this want of union for concerting some general plan is the most favourable circumstance to us, in our designs against so powerful a people. It is seldom that two or three communities concur in repelling the common danger; and thus, while they engage singly, they are all subdued.’ (Tacitus Agricola 12)

Julius Caesar mentions a series of tribes and rattles off a few aristocratic names in the Gallic Wars. Ultimately, however, he leaves his audience in the dark as to the specifics of British society and politics beyond noting that ‘the interior of Britain is inhabited by people who claim on the strength of their own tradition to be indigenous; the maritime portion by immigrants from Belgic territory who came after plunder and to make war, nearly all of them being named after the tribes from which they originated’ (Gallic Wars 5, 12).

Our understanding of society in the British Iron Age is therefore both incomplete and severely limited. We do not know how people were organised or what they thought of themselves or their leaders. The names that we have for the different tribal groups, such as the Iceni, the Atrebates and the Catuvellauni, are those preserved by the Roman State in the late first and early second century AD. It is highly probable that, in establishing this organisational framework, Rome recognised only the larger political groupings, disregarding all others. The real political map of Iron Age Britain was no doubt simplified by Rome who preferred the idea of single tribes occupying single areas under the rule of individual leaders. More likely the names that we have today for the ‘tribes’ of Britain were no more than the identifiers of particular ruling dynasty or aristocratic lineage. A ‘tribe’ could simply have been those who owed allegiance to a particular leader and not necessarily always a discrete ethnic or cultural group.

It was the aristocracy, the non-productive elite, holding power through military supremacy, trade, divine right or blood heritage, who decided whether external influences, such as those presented by the Roman Empire, would succeed within particular areas. If the leaders wanted wine and olive oil then it was up to them to negotiate directly with Rome. Any subsequent widening of access to Roman goods, fashions or customs to the population would depend on how tightly leaders controlled their followers and how many gifts and favours they ultimately bestowed.

Parallels for the successful development of power through the brutal control of business and the exploitation of family networks can be found throughout human history, particularly in early twentieth-century America. Here, groups operating small-scale urban criminal activities in New York, eventually grew to control significant areas of the city. By the time of prohibition in the 1920s, when the sale and consumption of alcohol was banned across the United States, the manufacture and distribution of bootleg liquor proved the perfect way for aspiring gangsters to further develop and expand their criminal empires. The exploitation of natural resources in return for Mediterranean consumables such as wine may have provided a similar route to the top for prehistoric entrepreneurs in Britain. As with the ‘royal’ houses of the British Iron Age, the control of business and the organisation of protection rackets in early twentieth-century America increasingly came under the control of a few powerful dynasties.

There was never a chance, in Late Iron Age Britain, that everyone would enjoy the proceeds of trade, exchange and big business. Tempting though it may be to see new Mediterranean imports into Britain as the beginnings of a better, more civilised society of benefit to all, there does not seem to have been much of a ‘trickle-down’ effect, with those beyond the elite suddenly shaving, bathing, drinking wine and wearing Roman gold. Only those with direct access to the Roman State would benefit from its patronage. Mediterranean contacts and the goods they provided were no doubt jealously guarded by the native elite, keen that the prestige associated with links to the Empire was not diluted by broadening access.

SETTLING DOWN

Across southern Britain, the most representative archaeological-type site of the Iron Age is the hillfort (Image 8). These imposing, contour-hugging enclosures seem to provide confirmation of the warlike nature of Iron Age society which, we are told by Roman writers such as Julius Caesar, was always feuding, brawling, fighting and stealing. Strong hilltop defences must, we assume, imply a very real fear of neighbouring communities combined with the desire to protect house and home from attack (Image 9). The majority of Iron Age settlements at this time, however, were relatively small-scale; representing close-knit farming communities, trading, interacting and existing in a relatively open landscape apparently without ever feeling the need to massively defend or protect.

8. Cleeve Hill Camp Iron Age hillfort, Gloucestershire. (Courtesy of Hamish Fenton)

9. Maiden Castle, Dorset. The southern ramparts of the multivallate Iron Age hillfort.

10. Cranborne Ancient Technology Centre, Dorset. A recreated Iron Age roundhouse.

The roundhouse was the standard domestic unit within most Iron Age settlements (Image 10). The size of floor varied, but most houses lay within the range of between 10 and 15m in diameter, defined by low external walls and, it is presumed, conical thatched roofs. ‘Open settlement’ roundhouses tended to cluster in groups of three or more, one structure serving as the main residential unit, others as ancillary buildings, storerooms and, occasionally, shrines (Image 11). Enclosed farmsteads, comprising a single, enlarged roundhouse set within a bank and ditch defining an area of around a hectare, are also found throughout the British Isles.

Warfare between the various Early Iron Age communities of south...