- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

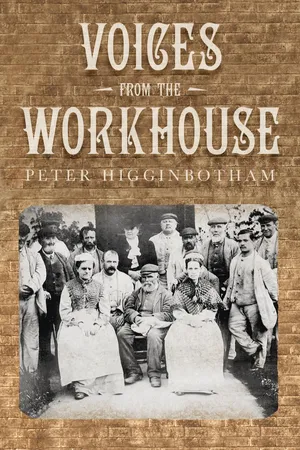

Voices from the Workhouse

About this book

Voices from the Workhouse tells the real inside story of the workhouse - in the words of those who experienced the institution at first hand, either as inmates or through some other connection with the institution. Using a wide variety of sources — letters, poems, graffiti, autobiography, official reports, testimony at official inquiries, and oral history, Peter Higginbotham creates a vivid portrait of what really went on behind the doors of the workhouse — all the sights, sounds and smells of the place, and the effect it had on those whose lives it touched. Was the workhouse the cruel and inhospitable place as which it's often presented, or was there more to it than that? This book lets those who knew the place provide the answer.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Voices from the Workhouse by Peter Higginbotham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

INMATES

OVER THE CENTURIES, the numbers of individuals passing through the gates of the workhouse ran into millions. Yet first-hand accounts of their experiences by workhouse inmates are relatively few and far between. Many paupers would, of course, have had a limited degree of literacy. For those who would have been able to record a written account of their encounter with the institution, there was probably little incentive to do so. Anyone struggling to regain their independence outside the workhouse was likely to have rather more pressing concerns, such as providing a roof over their head and putting food on the table. Besides, who would be interested in hearing about an experience which was both commonplace and also widely regarded as deeply shameful? It is perhaps not surprising then, that such accounts as do survive are often anonymous or never intended for publication. One source of workhouse memoirs that did reach a wider audience comes from those who ultimately made a success of their lives and were then happy to reveal their humble origins to an interested audience.

Whatever a person’s life story, or the reasons for their words coming down to us, their views of the workhouse have always to be viewed in the context in which they were recorded. Recollections of the time spent in a workhouse can often create an unbalanced view of the institution as they inevitably tend to focus on the most memorable or distressing aspects of the experience. Conditions inside the workhouse and the treatment received by inmates also have to be measured by the contemporary standards typically experienced by those outside the establishment. Workhouse food may have been plain and repetitive, but certainly no worse than the diet of many independent labourers and their families. The flogging of boys in workhouse schools may seem barbaric, but this was the norm in many Victorian children’s institutions.

This collection begins with two of the earliest surviving workhouse ‘voices’. In both cases, although the words recorded were spoken (or sung) by workhouse inmates, they were composed by others. Nonetheless, each provides an interesting insight into the workhouse experience in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries when children often featured prominently in workhouse populations.

London Corporation Workhouse

Poor Out-Cast Childrens Song and Cry

The London Corporation of the Poor was first established in 1647 under An Ordinance for the Relief and Employment if the Poor, and the Punishment of Vagrants and other Disorderly Persons, whose provisions included the erection of ‘work-houses’ – one of the first pieces of legislation to employ the word. The Corporation was given two confiscated royal properties – Heiden (or Heydon) House in the Minories, and the Wardrobe building in Vintry – in which it established workhouses. By 1655, up to a hundred children and 1,000 adults were receiving relief via the establishment although residence was not a prerequisite. Adults could perform out-work in their own homes, or carry it out each day at one of the workhouses. As well as basic literacy, children in Corporation care were taught singing. A verse of one of their songs, very much a propaganda piece for the Corporation, paints a very rosy picture of their treatment:

In filthy Rags we clothed were;

In good warm Raiments now appear

from Dunghils to Kings Palaces transferr’d,

Where Education, wholesom Food,

Meat, Drink and Lodging, all that’s good

For Soul and Body, are so well prepared.5

Lack of funds hindered the Corporation’s activities and a later verse of the song makes an explicit appeal to the parliamentary legislators who in the mid-1650s were prevaricating on a scheme to expand England’s fishing industry to the detriment of other nations such as the Dutch and Danes:

Grave Senators, that sit on high,

Let not Poor English Children die,

and droop on Dunghils with lamenting notes:

An Act for Poor’s Relief, they say,

Is coming forth; why’s this delay?

O let not Dutch, Danes, Devils stop those Votes!

The Corporation’s activities came to a halt with the Restoration in 1660 when Charles II reclaimed his properties.

John Trusty

Dinner Speech at the Bishopsgate Workhouse

In 1698, the newly revived City of London Corporation established a workhouse on Bishopsgate Street, on what is now the site of Liverpool Street station. In 1720, the workhouse was said to be ‘a very strong and useful Building, and of large Dimensions, containing (besides other Apartments) three long Rooms or Galleries, one over another, for Workhouses, which are all filled with Boys and Girls at Work, some Knitting, most Spinning of Wool; and a convenient Number of Women and Men teaching and overseeing them; Fires burning in the Chimneys in the Winter time, to keep the Rooms and the Children warm.’6 The children, up to 400 in number, were taught to read and write, and given work to do until they could be put out to be apprentices, sent to sea, or ‘otherwise disposed’. The youngsters all wore clothing made from ‘Russit Cloth’7, with a round badge worn on the breast representing a poor boy and a sheep with the motto ‘God’s Providence is our Inheritance’.

On 29 October 1702, John Trusty, an eleven-year-old boy from the workhouse, was selected to make an address to Queen Anne at the Lord Mayor’s Day dinner in the Guildhall. Although clearly penned by someone else, his words – possibly the earliest on record spoken by an identifiable workhouse inmate – conjure up a rather charming scene:

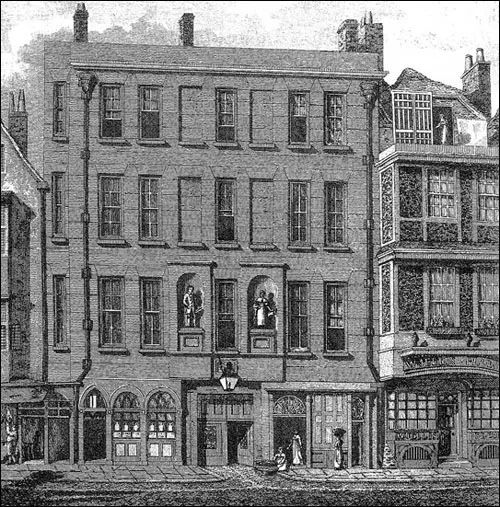

The front entrance of the city of London’s Bishopsgate Street workhouse.

May it please Your Most Excellent Majesty: To Pardon this great Presumption in Us poor Children, who throw our Selves at your Royal Feet, among the Rest of your Glad Subjects, who here in Crowds appear to behold Your Sacred Majesty.

We, MADAM, have no Fathers, no Mothers, no Friends; or, which is next to none, those who through their Extreme Poverty cannot help us. God’s Providence is our Inheritance. (Pointing to the motto on his breast.) All the Support we have is from the Unexhausted Charities of Your Loyal Citizens of London, and other Your Good Subjects, and the Pious Care of our Governors, who are now teaching our little Hands to Work, and our Fingers to Spin.

These Threads, MADAM, (Holding some yarn in his hands) are some of the Early Fruits of our Industry. We are all daily employed on the Staple Manufacture of England, learning betimes to be useful to the World. And there seemed nothing wanting to compleat our Happiness, but the Opportunity which this Day affords us, of being the Objects of Your Tender Pitty and Compassion. One Gracious Smile from YOUR MAJESTY on this New Foundation will make us Live, – and Live to call You Blessed.

And may God Almighty long Preserve YOUR MAJESTY for the Good of these Your Kingdoms, and Your Royal Consort the PRINCE. So Pray We, Your Little Children: And let All Your People say, AMEN.8

Paul Patrick Kearney

London Pauper Farms

In the eighteenth century, parishes in the city of London increasingly moved away from running their own workhouses and instead used the services of private contractors who operated ‘pauper farms’, often located outside the city boundaries.

One inmate of such an establishment was Paul Patrick Kearney, a colourful and disreputable character who was finally reduced to claiming poor relief from the City parish of St Dionis Backchurch where he had legal settlement.9 In 1764, after his initial requests for relief were turned down by two of the churchwardens, Kearney – as was every applicant’s right – took his case to the Lord Mayor of London who, like local justices of the peace elsewhere, could overrule such decisions. Churchwarden William Kippax then agreed to offer Kearney relief which, to Kearney’s horror, consisted not of the anticipated handout but of a note of admission to the parish’s pauper farm – or ‘mock workhouse’ as Kearney referred to it. The note, as Kearney later related, was addressed to the farm’s proprietor:

One Richard Birch in Rose Lane in the parish of Christ church Spitalfields in the county of Middlesex not only out of the said parish of Saint Dionys but also out of the city of London and Jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor which written note instead of being an order for this informants relief was a warrant of commitment of this informants body to imprisonment labour or work in an infected filthy dungeon called a work house kept by the said Richard Birch containing near one hundred poor victims to parish cruelty but not capacious enough healthily to hold forty persons, and therein the said Birch grossly insulted and abused and ordered [me] to work at emptying the soil out of vaults that pass in drains or sewers through under or in the said mock work house which so overcame [me, that I] fainted and fell sick and was in that condition forced into a nasty bed where [I] was swarmed with lice and got the Itch mange and a malignant or pocky leprosy.10

Although conditions on pauper farms had a poor reputation, the woeful picture painted by Kearney is clearly one whose intent is primarily to provoke sympathy for his claim for out-relief.

For several years afterwards, Kearney managed to extract relief from the parish in various forms including cash, lodging, clothing and medicine. In February 1771, by which time the parish was housing paupers with a contractor at Hoxton, Kearney was again petitioning the Lord Mayor. On this occasion, his pleas were heard by a sitting of aldermen who:

Sent me into prison to be bodily & unlawfully punished & mentally tortured in a Slaughter house for poor human bodies unlawfully kept by John Hughes & Wm Phillips & their accomplices at Hogsden [Hoxton].11

At a subsequent inspection of the Hoxton workhouse by the St Dionis churchwardens, Kearney complained:

I was perishing of cold for want of clean warm apparel & lodging ill of a complication of distemper occasioned by the cruelties exercised on me at Birches &c and that I could not eat half the victuals allowed me because of my illness & their being cold & not warm victuals fit for an ailing person, nor any spoon meat not even Sage tea & but 3 pints of small beer which occasion’d my drinking more water there than beer daily, and that I was insulted tormented vexed & otherwise constantly abused in so much that my life was a burthen to me there.12

Soon afterwards, Kearney proposed that in return for a one-off payment of forty shillings, he would agree never again to claim relief from the parish. The money was to allow him to take up a post as secretary to a Captain Scot who was embarking on several years of travels abroad. Although it is not clear if the money was paid, Kearney was not heard from again.

Ann Gandler

Reflections on My Own Situation

Ann Candler was born in 1740 at Yoxford in Suffolk, the daughter of glover William More and his wife. As a child, Ann displayed a ‘fondness for reading’, her favourites being travel books, plays and romances, though not poetry. Despite this, her first efforts after learning to write were in verse.13

In 1762, she married a man named Candler, a cottager from the nearby village of Sproughton. Candler’s heavy drinking, coupled with his service in the militia from 1763 to 1766, kept Ann and her growing family destitute. When Candler re-enlisted in 1777, Ann was ill for eleven weeks and was forced to put four of her six children into the Tattingstone workhouse. In 1780, she took refuge in the workhouse herself, where she gave birth to twin sons, an event which became the subject of one of her poems. Sadly, both twins died after a few weeks. Following Candler’s military discharge in 1783, the two of them entered the workhouse. Six months later, Candler departed – the last Ann ever saw of him. Remaining in the workhouse, she began writing more poetry, some of which was published by the Ipswich Journal. She gained several literary patrons, including the poet Elizabeth Cobbold, and in 1802 advance subscriptions for a small volume of her poems, Poetical Attempts, enabled Ann to take furnished lodgings near h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- A Workhouse Timeline

- One Inmates

- TWo Workhouse Staff and Administrators

- Three Reports and Inquiries

- Four Social Explorers

- Five Visitors

- References and Notes

- Copyright