![]()

1

AN EXCEPTIONAL MAN …

AN EXTRAORDINARY PERSONALITY

‘Wingate was a strange, excitable, moody creature, but he had fire in him. He could ignite other men.’

Field Marshal Viscount Slim

BRITISH COMMANDERS in the Far East had dismissed Japanese fighting qualities but then suffered humiliating defeats after the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941. These crushing blows shifted opinion from one extreme to the other. J.P. Cross (Jungle Warfare) wrote that the prevailing view of the Japanese as ‘second rate soldiers’ changed rapidly. Now the enemy were regarded as

… supermen, experts in the jungle in a way never previously imagined, invincible, brave to a degree unsuspected and malignantly cruel in a manner few had ever contemplated modern man could be. They also despised the softness and lack of military endeavour in their enemies. They used the jungle as a conduit of movement; the Allies tried to fight the jungle and the enemy and, to start with, were unsuccessful against both.1

The Japanese soldier’s aggression commanded respect:

They fought with savage and, at times, hysterical fury. They were very brave. If 50 Japanese were holding a position, 45 of them would have to be killed before the rest would kill themselves and the position could be taken.2

Most Allied commanders – General (later, Field Marshal Viscount) Slim included – acknowledged this bravery. Slim commented:

The strength of the Japanese Army lay not in its higher leadership, which, once its career of success had been checked, became confused, nor in its special aptitude for jungle warfare, but in the spirit of the individual Japanese soldier. He fought and marched till he died.3

Yet the Japanese were not invincible. They were poorly organised and had a strange lack of discipline. Cross wrote: ‘Fighting patrols, of about 20 men, were not very skilful. They liked to keep to paths and moved without precaution, often giving their presence away by soldiers talking.’4

Beyond fighting quality the Japanese drew strength from their recognition of the jungle as shelter and shield, rather than a second enemy. The Allies had no choice here: they had to adopt a similar attitude if they were to prevail. This change would take time. Certainly, it came too late to save Burma from conquest in 1942. It would take a truly exceptional man, with an extraordinary personality, to bring such change.

Orde Charles Wingate is by no means unique. Over the centuries many British military leaders of extraordinary quality have emerged to shape the course of events. It is not unusual for such reputations to be built on a combination of eccentricity and ability. Such men tend to make enemies among able yet more conventional men. From the very first, the entire enterprise – the strategic and tactical principles of Long Range Penetration and the fundamentals of what it meant to be a Chindit – belonged to Wingate alone. There were two Chindit expeditions: the Brigade-scale Operation Longcloth in 1943 and the much larger Operation Thursday in 1944. If a fundamental criticism can be levelled at Wingate, it is that LRP and the man became indivisible. He made himself virtually irreplaceable and, in doing so, exposed his force to much abuse after his untimely death in March 1944.

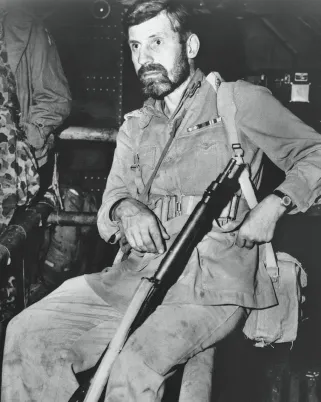

Eccentricity, ability and vision: Orde Charles Wingate, pictured in the final hours before his death in an air crash. (Trustees of the Imperial War Museum)

Wingate was born at Naini Tal, in the Himalayan foothills, on 26 February 1903. His parents were Plymouth Brethren, a strongly puritanical sect. Colonel Wingate, having returned to England with his family, led a spartan existence. Much of the family income was devoted to missionary causes. The Wingate children received their early education at home, away from other children.

Orde Wingate was a loner at Charterhouse School. He left in 1920 and entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He sought a commission in the Royal Artillery and joined 5 Medium Brigade. ‘Cousin Rex’ (Sir Reginald Wingate, a former Governor-General of the Sudan and High Commissioner of Egypt) watched over his progress. Presumably, Wingate took his advice; he enrolled at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.5

When posted to Egypt Wingate sent his luggage ahead, cycled across Europe and joined a ship at Genoa. In 1928 he was posted to the Sudan Defence Force. He was to spend six years in the Sudan. Wingate’s appetite for exotic adventure led to an expedition with camels into the Libyan Desert in early 1933, ostensibly searching for the ‘lost oasis’ of Zerzura. He lived hard on dates, biscuits, cod liver oil and oranges. This foray allowed the 30–year-old Wingate to develop his qualities of leadership and self-discipline.6

Two life-changing events then occurred. During the voyage home from Egypt in March 1933 he met his future wife, Lorna Patterson, who was then just 16. They married on 24 January 1935. The second was his posting to Palestine, as an intelligence officer with 5th Infantry Division. The 1917 Balfour Declaration supported a Jewish National Home in Palestine, but no-one, at that time, could have foreseen the rise of Nazi Germany less than 20 years later and its pitiless persecution of the Jews. Jewish immigration in the wake of the Nuremburg Laws triggered more violence in Palestine. There was much British sympathy for the Arabs, but Wingate held a contrary view; he and Lorna became fervent Zionists.7

Wingate was self-opinionated, entirely free of selfdoubt and a dogged advocate of the Jewish cause. As a young officer he cultivated powerful friends and worked hard – propelled by a genuine empathy – to overcome Jewish suspicions. Slowly, the doubters were converted and his friends included Jewish Agency leader Chaim Weizmann. By early 1937 Wingate was arguing that the Jews should be armed. He then went further, making a dangerous offer to assist in the organisation of an underground Jewish Defence Force.7

Wingate was out of his depth in the circles of high politics. He was a soldier with a sharp political edge to his tongue, yet his strong views radiated from a naive inner conviction, rather than political interest. Wingate was blind to politics at the sophisticated level. Consequently, many regarded him as extremely dangerous – a loose cannon.

The Peel Commission proposed the partition of Palestine into British, Jewish and Arab zones. Arab attacks on Jewish settlements intensified as General (later, Field Marshal Viscount) Wavell took command in Palestine. Wingate even engineered an opportunity to board Wavell’s car, to have a face-to-face opportunity to present his ideas for Jewish night patrols to combat ‘terrorists’.

Wavell’s successor, General Haining, backed Wingate’s ‘Special Night Squads’; they began operating in June 1938. Each man was expected to be able to cover 15 miles of country by night. Each Squad had an Arabic speaker, to help win hearts and minds among local communities and make common cause against the ‘terrorists’. These squads were an outstanding success, although Wingate himself was wounded in a skirmish. These exploits earned him a DSO.8

In late 1938 Wingate was in London, at Weizmann’s request, pressing the Zionist case in the weeks leading up to the publication of another report, from the Woodhead Commission, but this had little effect. The report was negative towards Jewish interests and the Peel recommendation for partition was overturned. Wingate then came to Winston Churchill’s attention at a dinner party in November, when he seized his chance to explain why the Special Night Squads had been so successful. His story fired Churchill’s imagination; Wingate would be remembered. In contrast, Wingate’s relationship with the Army establishment (other than with one or two prominent champions) continued to sour. Back in Jerusalem he found the Night Squads now had a new commander. On the other hand, he continued to gain trust in Jewish circles and became known as ‘The Friend’.9

The first days of war saw Orde Wingate at his London flat, 49 Hill Street, unemployed but with powerful friends. They included Leo Amery (Secretary of State for India and Burma, May 1940–July 1945), who was to be instrumental in creating opportunities for Wingate in Abyssinia and, later, in the Far East. Yet Wingate’s outspoken Zionist views continued to stir resentment and his personality displayed more than a touch of paranoia. On meeting David Ben-Gurion (later to become Israel’s first Prime Minister) in London, he insisted they talk in a car, but not his car!

He was not alone in believing that he and the family were under surveillance. Writing in the early 1960s, Wingate’s mother-in-law, Alice Ivy Hay, claimed:

These apprehensions were not without foundation. In Jerusalem his telephone was tapped and many of his private letters were opened. He did not reject the possibility that recording machines might have been secreted in his apartment, or in his own car, and if ever he had anything important to say to anyone, he preferred to say it in the open – preferably in the middle of a field or open space. In London, his telephone was also tapped (and so was mine in Aberdeen).10

Thousands of men would be drawn to Orde Wingate’s Chindit standard in a new World War. They included Bill Towill, born in 1920 and the elder of two brothers. His father had been wounded and gassed in the Great War, but had recovered sufficiently to run the family farm near Totnes, Devon.

Towill shared something with Wingate: his family environment was also shaped by strict religious belief. Towill’s plans to become a solicitor were frustrated by war. Acting on conscientious grounds, he joined a local RAMC Territorial unit. The 11th Casualty Clearing Station was absorbed into the Regular Army within 72 hours of war being declared. They went to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The unit arrived at the little village of Pernois, near Amiens. The initial months of the ‘Phoney War’ passed quietly, yet there was a sobering reminder of reality nearby: a huge cemetery for thousands slaughtered in the mud of the Somme.

When the storm broke in May 1940, the German Blitzkreig sought to trap the BEF and the French northern armies against the coast. Towill’s medical unit moved into Belgium but soon joined the general retreat towards the sea. Events pushed Bill Towill towards a crisis of conscience:

‘It was the early morning of Friday, 31 May, exactly three weeks after the start of the Blitzkrieg, and we were at a little seaside resort called La Panne, just inside the Belgian border and some 11 miles along the beach from Dunkirk. Much of the BEF had already been evacuated. I came off night duty and found the rest of the unit formed up on the beach. We were told we were about to march off, but volunteers were wanted to stay with the wounded. So, the order was given: ‘Volunteers, one step, forward march. Volunteers stand fast – remainder dismiss!’ Too many men volunteered. The order was given a second time and still too many volunteered. Yet again the order was given and four of my colleagues and I were left. The rest moved off towards Dunkirk and we were joined by 20 volunteers from other medical units in the area. We were now under the command of Major J.L. Lovibond, one of our officers.’

A large casino on the beach served as a hospital, but heavy shelling prompted a move to the underground shelter next door:

‘The beach was under sporadic shellfire. This caused a lot of casualties among those still making their way past us, on to Dunkirk. We stretchered the wounded back to the shelter and gave what help we could. When night fell it became pitch black. We had no light to carry on, except from the flash of bursting shells. Chunks of shrapnel churned up the sand around us but, miraculously, we weren’t hit.

‘At about 2am on Saturday, 1 June, a few of us accompanied the Major into the casino’s huge ground floor room, which had been turned into a morgue. Around the walls, in orderly rows, were laid the bodies of scores of our dead. We had no chance of giving them proper burial. The Major did the best he could by reading the Burial Service over them. In the inky blackness, the only light was from the tiny flashlight the Major used to read from his prayer book. This reflected the light onto the lower half of his face. He came to a quite amazing passage, from Revelations 21: “And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.”

It would be difficult to over-state the impact of these words, in those circumstances, on a deeply religious 19-year-old lad. The sorrow, pain and death filling all our waking moments during the last three weeks seemed to have eaten into our souls. These great words of hope brought a special uplift to our failing spirits.’

Bill Towill’s future as a Chindit during the second expedition, with 3rd/9th Gurkha Rifles, was determined by the luck of the draw:

‘A couple of hours later the Major called us all together again. The last of our men had long since gone past us and we were quite alone. The Major said the Germans were just down the road and would soon be arriving. There was no need for all of us to be taken prisone...