- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Tempus History of Wales 25, 000 BC to AD 2000.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Tempus History of Wales by Prys Morgan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

WALES’ HIDDEN HISTORY

c.25,000 BC – c.AD 383

Edited by S. Aldhouse-Green, with contributions by S. Aldhouse-Green,

M.J. Green, M. Hamilton, R. Howell & J. Pollard

M.J. Green, M. Hamilton, R. Howell & J. Pollard

HUNTER-GATHERER COMMUNITIES IN WALES

Stephen Aldhouse-Green

Wales is first known to have been peopled a quarter of a million years ago. From then, until as recently as 9200 years ago, Wales was only inhabited episodically because of dramatic shifts both in climate and sea level. Even then, during what is usually termed the Postglacial period, the land continued to be peopled by hunters, gatherers and fishers until the arrival of the first farming communities some 6000 years ago. This period of 250,000 years can be divided up in several different ways, whether by types of human being, archaeological period, or climatic phase. My approach here will be to take a few important sites and use these as a snapshot of life in prehistoric Wales.

The Paleolithic

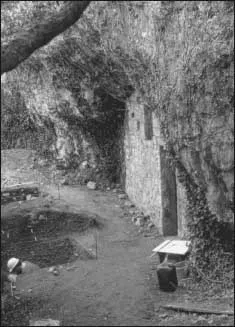

Pontnewydd Cave was first recorded in the 1870s by McKenny Hughes and Boyd Dawkins. By this time a length of 25m of deposit had been excavated or quarried away and archaeologists generally believed that the cave had been cleared of all archaeological evidence. A few stone tools had been found along with bones of Ice Age animals and a human tooth believed to have been ancient and, presumptively, Neanderthal. A programme of excavation, initiated in 1978 and continuing until 1995, revealed a remarkable fact: that the cave had been infilled by a series of mud-slides or debris-flows. This meant that evidence of human settlement, in the form of stone tools and actual human remains, was preserved deep within the cave system.

The archaeological evidence from Pontnewydd shows that the main occupation took place around 225,000 years ago, possibly just after a temporary period of severe cold. The bones of many species of animal were found mixed with artefacts, including numerous stone handaxes, sharp flakes and points, and hide-scrapers. The animals included rhinoceros, leopard, hyena, bear and horse. Only the last two can definitely be associated with the human presence at the site, for some of their bones had been cut-marked with stone tools. It evokes an image of Neanderthals, armed with thrusting spears and javelins, hunting horse in the open ground of the Elwy Valley or venturing into the dark recesses of the cave at times when it was used by hibernating bears and killing and dissecting a bear for the skin and meat.

The occupants of the site were not modern humans but Neanderthals. These latter had evolved in Europe where they can be recognised with confidence from c.300,000 years ago or earlier. However, our best evidence for Neanderthals comes from the last cold period (broadly the last 100,000 years) during which not only are remains more abundant, but actual burials occur in which the skeletal remains are, in consequence, complete. From these a detailed picture of Neanderthal physique and physiology may be built up. The body from the neck down was similar to our own but was very much more robust, a reflection of constant activity. The lower arms and legs were relatively short in relation to the thighs and upper arms, an adaptation seen among circumpolar peoples which is designed to conserve body heat. In just the same way, the large nose may also be a cold climate adaptation, enabling the warming of air before it entered the lungs. Other features of the face were a low forehead with the eyes consequentially placed high on the face. These eyes, large in size, looked out from beneath generous brow ridges. Finally the middle of the face was ‘pulled forward’ and the chin was missing. DNA has been found preserved in the bones of Neanderthal skeletons and shows that this is indeed a separate species which died out without significant evidence of having interbred with modern humans. These latter had evolved in Africa and colonised Europe from about 40,000 years ago, reaching Wales 10,000 years later.

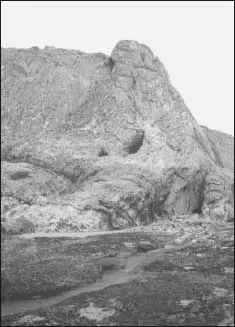

Paviland Cave is a site with at least half a dozen separate phases of human presence. Although the site was once deeply stratified, the poorly recorded activities of excavators, combined with the action of the sea, have destroyed much of the evidence of their original sedimentary contexts.

Neanderthals were almost certainly present at Paviland. It seems likely that they visited Coygan Cave near Laugharne, across the then dry Carmarthen Bay, some 50,000 years ago. There seem to have been two points in time when Neanderthals were present in western Britain. First, it may be that a colonising group of Neanderthals arrived around 50,000 years ago or a little earlier when the climate, ameliorating after the extremely cold conditions of the period between 75-60,000 years ago, had opened up the northern lands of the British peninsula to settlement. These settlers are associated with distinctive hand axes. They take a subtriangular form whose affinities lie with a French industry made by Neanderthals and sometimes known as the hand axe Mousterian. Artefacts probably of this age at Paviland are likely to belong to this industry, which would appear to be virtually the only Mousterian cultural assemblage represented in Britain. It may of course be the case that the distinctiveness, and therefore the archaeological visibility, of the hand axe forms is a factor in their preferential recognition. However, it now seems clear that the known Mousterian facies on the Continent represent a chronological succession. The hand axe Mousterian is the last of the succession of Mousterian assemblages and it is probably the case that humans were simply not present in Britain during the last cold stage until after its appearance on the Continent after 60,000 years ago.

Second, the later Neanderthals are probably to be associated with the industry typified by leaf-shaped spearpoints, sometimes known in Britain as the Lincombian. As originally set out, this term defined a mixed industry in which Aurignacian artefacts – that is to say the tools of the earliest modern humans in Europe – and leaf-points were associated. Increasingly the term is used to refer to British leaf-point industries regardless of whether or not other elements were mixed in.

These two Neanderthal phases are to some extent notional. It is not clear whether there was continuous settlement of the British peninsula nor whether Neanderthals were still present in Britain when anatomically modern humans – probably to be identified with people of Aurignacian material culture – first arrived. It seems likely, however, that Neanderthal presence was confined to a number of discrete episodes in keeping with broader evidence for episodic human peopling of the more northerly parts of Europe. It is a reasonable expectation, moreover, given the complexity of the climatic history of the last glacial period, that such presences may have coincided with the milder, so-called ‘interstadial’ periods which are known to have occurred as episodes within the cold glacial stages.

The richest of the archaeological assemblages at Paviland is the Aurignacian. This is represented artefactually by a series of distinctive stone tools including specialised forms of engraving tools and scrapers. These cannot be directly dated but they are likely to be of the same age as large quantities of bone charcoal dated to c.29-28,000 years ago. This dating is not only supported by the appearance of burnt Aurignacian artefacts at Paviland, but also from the dating of an Aurignacian bone spearhead found at Uphill to around 28,000 years ago. However, the most important phase in the history of the site dates to 26,000 years and concerns a burial known as the ‘Red Lady’. Only the left side of the skeleton survived to be recovered by Dean Buckland in AD 1823, who described the skeleton as:

…enveloped by a coating of a kind of ruddle… which stained the earth, and in some parts extended itself to the distance of about half an inch [12 mm] around the surface of the bones… Close to that part of the thigh bone where the pocket is usually worn… surrounded also by ruddle [were] about two handfulls [sic] of small shells of the Nerita littoralis [common periwinkle]… At another part of the skeleton, viz in contact with the ribs [were] forty or fifty fragments of ivory rods… from one to four inches in length… [Also]… some small fragments of rings made of the same ivory and found with the rods… Both rods and rings, as well as the Nerite shells, were stained superficially with red, and lay in the same red substance that enveloped the bones

Buckland Reliquiae Diluvianae

Positioned nearby was the skull of a mammoth which may have played a part in the ritual of the burial and so became part of the grave furniture. It was certainly a commonplace among comparable European burials for remains of mammoth and rhino to be included in the grave or form a part of its structure. Some such burials seem to have been the graves of shamans and it is possible that such animal remains may symbolise the shaman’s spirit helper.

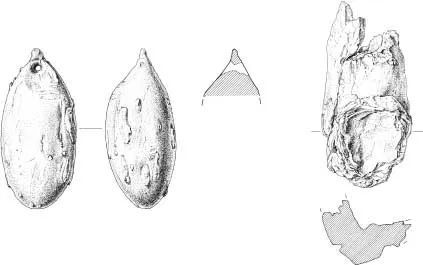

The period following the burial was one of extreme cold leading to the peak of the last glaciation at 20,000 years ago when most of Wales disappeared under vast sheets of glacial ice. Even so, visits to Paviland Cave continued. Two represent episodes of ivory-working on the site (at 24,000 and 21,000 years ago). The earlier of these is marked by the manufacture on site of a unique ivory pendant made from a growth in the tusk of a mammoth. A further event 23,000 years ago involved a deposit of three schematic anthropomorphic figurines of a kind undocumented in Western Europe but with parallels on the Russian plains. It is postulated that these were visits by far ranging task groups for whom the site had a sacred as well as a secular importance.

With the coming of the ice sheets, Wales was abandoned. Eight thousand years later, around 13,000 years ago, during a period of mild climate, hunter-gatherers reoccupied Wales. The history of that period can be pieced together from the finds at a number of caves, most notably Hoyle’s Mouth near Tenby where the discovery of flints deep in the darkness zone of the cave is suggestive of initiation rites or possibly shamanic rituals. The reoccupation of Wales was, however, a false dawn. During the eleventh millennium, cold climate returned and, for the most part, people migrated south. Wales was eventually re–populated around 9200 years ago and that date presents a mystery for it falls fully 500 years after the colonisation of England. At this stage it is not clear whether this late adventus of the Mesolithic postglacial hunter-gatherers was a genuine historical fact or whether evidence is yet to be found for settlement earlier in the tenth millennium.

2. Pontnewydd Cave. Excavations here yielded remains of six Neanderthals dated to around 225,000 years ago.

3. Paviland. Goat’s Hole controlled a possible animal migration route to the Gower plateau and overlooked an area of plain. It was well positioned as a hunting intercept site. It was also the site of the ceremonial burial of the so-called ‘Red Lady’ interred 26,000 years ago.

4. Paviland Cave. Ivory Pendant and fragment of mammoth tusk. This artefact was shaped around 24,000 years ago from a natural growth in the tusk of a mammoth. The fragment of diseased tusk illustrated here was excavated by Buckland in 1823. The pendant was found by Sollas in 1912.

The Mesolithic

Mesolithic settlement was focused on the coastal plains and the uplands seem to have been exploited only by specialist hunting groups. Beaches provided the coastal dwellers with easily accessible raw materials in the form of flint, chert and occasional flakeable volcanic rocks. In the midst of the Mesolithic, at c.8500 years ago, Britain finally became an island and one time hunter-gatherer territories were progressively submerged. The sites of Frainslake and Lydstep amid the submerged forests of Pembrokeshire bear particular testimony to this process. At Frainslake a probable Late Mesolithic flint scatter was associated with a windbreak of gorse, birch and hazel which ‘ran in a gentle curve for 4-5 yards’. Again, at Lydstep a pair of microliths – perhaps components of the armature of a Mesolithic arrow – was found in a context suggestive of the arrow having been embedded in the neck of a pig.

The postglacial rise in sea level, and consequential inundation of the coastal plains, may have had an impact on the diet and social relations of the hunters. The sea now lay in many areas at the foot of high cliffs and it may be that it was there some groups were denied access to the sea. This may explain the evidence of nitrogen and carbon ratios in human bone which suggests that some of the very latest Mesolithic people in Wales had moved to a diet composed of meat or cereals. This is in direct contrast to the evidence of the exploitation of sea-foods seen in the earlier Mesolithic people. In this period raw materials for stone tools were more local in origin, again implying reduced territorial ranges and reduced mobility. Other key changes in the Mesolithic were progressive afforestation, a change at c. 8700 years ago from broad blade to narrow blade microlith forms used as arrow armatures and finally evidence for the human management of the landscape through the use of fire to create cleared areas in order to foster aggregations of game.

Wales has a multitude of Mesolithic sites but has no certain evidence of houses or long term campsites which may have been used as home bases. The Nab Head, Pembrokeshire, has occupation in both early and late phases of the Mesolithic. The site is located on a promontory high above the sea but would have lain, during its early Mesolithic occupation, on a hill with gently sloping sides easily accessible to the then coastal plain. The Early Mesolithic site on the Nab Head produced no certain structures. It is, however, well known for the large numbers of perforated stone beads it has produced. In all 690 artificially perforated natural mudstone pebbles are known. A type of drill bit made of flint is common on the site and is called a mèche de foret; it is likely to have been associated with stone bead production. There has been speculation that the beads once formed sets of jewellery and came from disturbed burials on the site. Modern excavation has found no trace of these. There is evidence for traffic in these perforated stone beads, examples being known from south-west Wales at Palmerston Farm and Freshwater East and, in upland Wales, from Waun Fignen Felen in the Black Mountains of Breconshire. The latter was probably also a production site for it has yielded broken beads and a flint mèche de foret suggestive of on-site manufacture. The Waun Fignen Felen beads were made of a very unusual spotted mudstone, possibly selected for its aesthetic properties. The Late Mesolithic site at the Nab Head produced several features. One of these is a possible house-site: here, three concentrations of artefacts defined an ‘empty area’ around five metres in diameter, an area comparable in size with Mesolithic houses known from elsewhere in the British Isles. The ‘concentrations’ may represent middens of material discarded from activities associated with the house.

The upland moorland of Waun Fignen Felen preserves a number of lakeside sites and displays both early and Late Mesolithic periods of activity covering several millennia. Its upland setting is very unusual. Human presence there has been interpreted as seasonal hunting forays and certainly not as year-round exploitation. It is noteworthy that the artefacts found there generally reflect hunting rather than processing activities. There are several lithic scatter sites at Waun Fignen Felen which may once have been very short lived locations designed for hunting waterfowl. Some are located upwind of the point where use of the Haffes gorge could allow a hunter to approach the lake unseen. This upland site is one of a number presenting evidence of the use of fire to manage the local environment (here heathland) to create grazing for game. The mobility of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers is reflected by the distances that raw materials travelled to reach Waun Fignen Felen. Thus, during the Early Mesolithic phase there, both beach flint and Greensand chert were exploited. The nearest sources to Waun Fignen Felen would seem to lie at least 80 kilometres distant.

The site of Goldcliff lies on the edge of the Severn Estuary. Like Waun Fignen Felen, there is evidence for the deliberate use of fire with charcoal present in the peat surrounding the site and for hunting and fishing. Actual remains attest the presence of red deer, roe deer, wild pig, wolf and otter; hoof-prints of aurochs and red deer are present. Birds identified include coot and possibly mallard and a number of fish species have been recovered. The settlement areas at Goldcliff lay on the former dryland margins of Goldcliff Island and arose from cyclical reoccupations of the reed swamp-fringed edges of the island. Exploitation of the local environment took place during a phase of marine regression. No house sites were found, nor constructed hearths, and the single posthole found was interpreted as possibly having formed part of a drying frame for smoking fish. Occupation in the winter to spring period has been inferred from a study of mammal and fish remains. Red deer, wild pig, roe deer and otter bones had all been butchered, presumably for human consumption. The occurrence of burnt fish and bird bones is suggestive of Mesolithic barbecues. Indeed, on one occasion two microlithic barbs of an arrow seem to have become embedded within a wild pig carcass and to have been roasted with it.

It is appropriate to leave the Mesolithic literally in the footsteps of its Mesolithic inhabitants. At Uskmouth near Newport, footprint trails preserved in intertidal deposits have been dated to the seventh millenium. Four humans were involved, three adults and a child. A perforated antler mattock found nearby, dated by radiocarbon to be more than 6000 years old, may have been used by one of the walkers. The area, then as now, was one of intertidal mud flats. Prints of animals and wading birds in the estuarine clay attest the richness of the environment of the last Welsh hunter-gatherer communities.

The Neolithic – Joshua Pollard

Defining the ‘Neolithic’ and understanding of the mechanisms of its introduction are subject to considerable debate. Traditionally, it has been viewed as the period that witnesses a shift from a subsistence base of gathering/hunting/fishing to one of settled farming, but the reality is more complicated. Not all Neolithic communities appear to have been fully fledged mixed farmers, and changes in su...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Editor’s Foreword

- 1 Wales’ Hidden History c.BC 25,000 – c.383 AD

- 2 ‘Dark Age’ Wales c.383 – c.1063

- 3 Frontier Wales c.1063 – 1282

- 4 Wales From Conquest to Union 1282 – 1536

- 5 From Reformation to Methodism 1536 – c.1750

- 6 Engine of Empire c.1750 – 1898

- 7 Wales Since 1900

- Further Reading

- List of Illustrations