![]()

CHAPTER 1

GERONTIUS

Gerontius must be one of the most influential Britons of whom nobody has ever heard. No, he’s not Elgar’s Gerontius and his dream, such as it was, was probably just one of power. He was a warlord who conquered Spain and Portugal with the help of British militiamen over a thousand years before Drake ‘singed the King of Spain’s beard’. He played a key part in the end of Roman rule in Britain and even, arguably, in the end of the Western Roman Empire, before dying with his wife in a blazing building surrounded by mutinous troops.

During the roughly three-and-a-half centuries that Britons were part of the Roman Empire, they played a distinctly low-key role in Roman political life. Other parts of the Empire such as Africa, Pannonia and Gaul produced a string of political figures who played a significant role in central Roman government, up to and including emperors. Britain, however, despite being the springboard for a number of attempts on the imperial throne (including those by the ill-fated Clodius Albinus at the end of the second century and the much more successful Constantine at the beginning of the fourth), produced throughout most of the Roman period few, if any, native sons or daughters who made a significant political impact in Rome. Two usurpers, the obscure Bonosus (c. 281) and the rather more successful and long-lasting Magnentius (ruled 350–353), both seem to have had British fathers – but equally both were born on the continent to non-British mothers.

The apparent reluctance of the British aristocracy to become involved in imperial politics, compared to their continental counterparts, may have much to do with the unusual nature of Rome’s occupation of Britain, when compared with the manner in which it controlled other parts of the Empire. Britain was the last major western territory added to the Empire. Parts of Africa, for instance, had already been occupied by Rome for almost 200 years by the time Claudius’ legions scrambled ashore on British soil. There had been a Roman province in the south of Gaul for almost as long, and it had been almost 90 years since Vercingetorix and his Gallic alliance had finally succumbed to Caesar. Britain, by comparison with most of the rest of the Empire, became Roman late and even then it was, in reality, only partially Romanised. We talk of the centuries of Roman occupation of (most of) Britain as ‘Roman Britain’, yet there was, in truth, nothing very Roman about much of Britain during this period. Southern, central and eastern areas do indeed show ample archaeological evidence of a widespread adoption of Roman lifestyles, but evidence of cultural Romanisation in Cornwall, Wales and north-west England is mainly restricted to ceramics, glass and a few trinkets. And the number of such artefacts becomes even smaller if we look further north. Scotland, of course, remained largely beyond Roman reach, both politically and commercially, which explains the scanty evidence there, but in Cornwall, Wales and north-west England the absence of evidence of Roman lifestyles must be seen, to some extent, as indicating a specific rejection of Romanisation. The inhabitants could have had access to a Roman lifestyle if they chose to. They did not.

Dragonesque brooches were made and worn in Britain well into the second century, showing a strong survival of British tastes and style under Rome.

Large parts of Britain, even where it was under Roman control, never adopted Roman culture. What’s more, even in the ostensibly Romanised centre, south and east of the island, it would be wrong to assume that the use of Roman items indicates that the locals had necessarily adopted a specifically Roman identity in addition to the trappings of the Roman lifestyle. In the same way, Britons today may wear American clothes, eat American food and listen to American music but none of this indicates that they see themselves as Americans.

As already touched upon, when the Romans took control of Britain in AD 43, they found an island occupied by a large number of different tribes, with different cultures, different backgrounds and maybe even, for all we know, different languages (or certainly very different dialects). Fighting between tribes and cross-border raiding were probably common phenomena. There was no such thing as a united British identity. The inhabitants of the island would have seen themselves as Catuvellauni, or Brigantes, or Dobunni, or Iceni, or Atrebates or any of a large number of other tribal identities. And the Romans did little to change this in the period after the invasion. Like all experienced imperialists, they wanted to control their new country with as little fuss and trouble as possible, and that meant, among other things, working with the existing traditional political structures rather than imposing a whole raft of new and different ones. In the Mediterranean regions where city-states had long been the building blocks of political life, the Romans gave them local political control, with each becoming on some level a smaller version of Rome itself. In Britain, where there were no city-states for the Romans to build on, they instead used the tribes as the basis for local government. The tribes became self-administering civitates (the Roman name for their key unit of local government) and the traditional British tribal aristocracies almost certainly largely remained in place as the leaders of these new civitates. A common feature of British archaeology in the early Roman period is the appearance of Roman-style villas near, or even on top of, significant pre-Roman dwellings, suggesting the widespread continuity of estates and land tenure from pre-Roman into Roman times. Even more significantly, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that Britons continued to see their national identity in terms of their former tribes, rather than gradually over the centuries coming to see themselves as ‘Britons’ or as Romans.

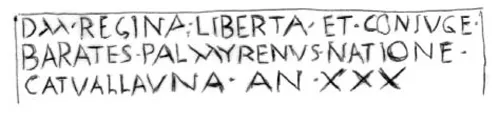

On a number of inscriptions from the Roman period we can see Britons clearly identifying themselves by their tribal nationality. A sandstone base at Colchester, for instance, carries an inscription referring to ‘Similis Ci(vis) Cant(iacus)’, a citizen of the civitas of the Cantii. A tombstone from South Shields records the nationality of Regina, wife of Barates the Palmyrene, as ‘natione Catvallauna’, ‘of the Catuvellaunian nation’ (8). A certain Aemilius, who had served with the Classis Germanica, is recorded on a tombstone from Cologne as ‘civis Dumnonius’, ‘a citizen of the Dumnonii’.1 References to individuals being British do appear on inscriptions, but these tend to be found not in Britain but on mainland Europe, where British tribal identities might, among a population largely ignorant of them, be expected to take a lower profile. Even at the end of the Roman period, just across the Channel one Sidonius Apollinaris identifies himself as ‘Arvernius’, one of the Arvernii, and his friend Aper as ‘Aeduus’, one of the Aedui. Similarly, many civitas capitals in Gaul abandoned their Roman names during this period and in common usage reverted simply to the name of the local tribe. Thus, for example, we have Paris (Roman Lutetia) from the Parisi, Avranches (Roman Ingena) from the Abrincati, Trier (Roman Augusta Trevorum) from the Treveri, and Vannes (Roman Darioritum) from the Veneti. In Gaul, however, any potential renewal of the expression of independent tribal identities was prevented by the introduction there of large Germanic kingdoms that directly took over from Roman control, and perhaps also by the more developed state of the Roman Catholic Church in Gaul at the end of the Roman period (as compared to the situation in Britain at the same time). If tribal identity could be so long-lived in Gaul, it would surely have been much stronger in a Britain that was Romanised later than Gaul and much less completely.

Inscription identifying a British woman as of Catuvellaunian nationality.

There is a sense also in literary references from the fourth and early fifth centuries that even after being part of the Roman Empire for hundreds of years, Britons were still seen as being somehow different and separate from the rest of the Empire. The poet Ausonius, for instance, composed a number of epigrams based on the assumption that being good and being British were mutually exclusive. Gildas also, writing perhaps 100 years after the end of Roman rule, shows no inclination to identify the British with people from the rest of the Empire. In his account of the arrival of the Romans in Britain and their departure he draws a consistently clear distinction between Britons and Romans. Perhaps it has something to do with Britain being an island. The rest of Western Europe seems to have adapted to inclusion in the Roman Empire with more enthusiasm. Perhaps we can see something similar today in the European Union. While countries like France and Germany, despite occasional gripes, seem happy enough to be integral members of the EU, Britain seems instinctively to want to keep itself separate. It remains a member of the EU, for the moment, because of the clear economic advantages from doing so, but one suspects that general British public sentiment remains deeply suspicious of the EU, even after decades of membership, and should the advantages of membership ever become less clear, there would doubtless be a serious push for the UK to leave, just as Britain was eventually to leave the Roman Empire in 409.

The pre-Roman tradition of conducting intermittent hostilities with neighbours seems to have continued into the Roman period. As mentioned in the Introduction, Boudica and her Iceni did not just attack Romans. They also targeted the Catuvellauni, a tribe with whom they may well have had long-standing border disputes (judging by the spread of Catuvellaunian coinage into formerly Icenian territory under Cunobelin, and by the digging of a probably pre-Roman defensive ditch, Mile Ditch, across the Icknield Way corridor near Cambridge).2 Equally, towards the end of the second century (in a move which has no contemporary parallel in other parts of the Empire) towns close to the borders around a number of British civitates (again including the Catuvellauni) were fortified, creating a defensive ring around these tribal territories. These defences are again suggestive of cross-border tribal raiding and should probably be linked to the appearance of two groups of villa and town fires identified within the territory of the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes. One of these groups of fires lies in the north-west of Catuvellaunian territory and, judging by the road layout in the area, could be linked to Brigantes raiding south from the Peak District. The second group lies in the Essex area and may be linked to Iceni raiding southwards from their tribal territory, just as they had under Boudica.3

There are also hints of internal trouble as well, in addition to raiding from outside Rome’s area of control, in the mysterious event of 367–369 that has come to be known as the ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’. Certainly the response to the events of those years seems to have involved a major tribal element. Military buckles and belt fittings appear across civilian areas and sites in the archaeologically Romanised areas of Britain, suggesting an arming of the civilian population (9), probably with official permission, judging by the appearance of a range of triangular plate buckles identical to those in use in military areas in mainland Europe. Different regional styles of buckle and belt fittings suggest the appearance of specific tribal militias in a number of different tribal regions (colour plate 10). This is consistent with the increasing establishment of private armies, known as bucellarii, in the Roman world in the late fourth and fifth centuries, and with the evidence of Roman use of tribal and civitas militias in a number of emergency situations at various other times across the Empire. For instance, an Athenian militia led by the historian Dexippus was used to repel marauding Goths in Greece in the late third century, and in 406 Honorius issued two edicts encouraging locals to volunteer for emergency defence.4 It is also consistent with Gildas’ description of the Romans arming the Britons before they finally left Britain, and with a number of inscriptions from Hadrian’s Wall which seem to indicate tribal units from the Dumnonii and Durotriges (and possibly the Catuvellauni) engaged in construction work on the wall and probably defending it too.5

British buckles from the end of the Roman period of the type probably worn by, and manufactured specifically for, British militiamen.

At the end of the fourth century and the beginning of the fifth there is more evidence of tribal border clashes. Late or post-Roman linear earthwork defences, in conjunction with concentrations of buckles/belt fittings and unretrieved hoards, suggest the possibility of conflict in a number of areas. The clearest case is perhaps in the Wiltshire/Avon area, where a line of burnt villas lies along the same axis as Wansdyke, a huge linear defensive earthwork probably separating the territory of the Belgae from that of the Dobunni. A rash of unretrieved hoards across the territory of the civitas of the Belgae also strongly suggests major trouble in this same area.6

It is in the context of all of this that we need to set the reluctance of the British aristocracy to become involved in Roman imperial politics. Certainly for almost the entire period of the occupation their political ambitions and aspirations remained at a tribal rather than an imperial level. Despite this persistent insularity, the beginning of the fifth century saw the arrival of two Britons who were to play a significant role in Roman political affairs. One would have been surprising enough, but the appearance of two such men is remarkable and is likely to indicate something very important about events in Britain as Roman power here died.

Traditionally the end of Roman Britain is regarded as taking place either in 409, when the historian Zosimus indicates that Britain rebelled against Rome, or in 410, when the E...