![]()

1

Wash Day

We had an outside coal place, lavatory and wash house. The wash house had a copper tub with a fire underneath, and a chimney which smoked. The copper fire burned everything; wood, rubbish, old shoes. Coal was too expensive for wash day. By the side of the copper was the dolly tub. A zinc barrel and a sort of plunger with four wooden legs – that was the dolly. Gran used to say, ‘Fifty jumps with the dolly please’, and I loved to hold it and jump it to wash the clothes, coloured ones in the dolly tub and whites in the copper. There were no detergents or soap powders. The soap was grated into flakes and washing soda added. Then the clothes were lifted from the copper with a big, strong copper stick. Next step, the wringer was used to get excess water out and finally they were put onto the clothes line hoping for a wind to dry everything.

On to the mangle house, which was Uncle’s wash house really, but the copper had been replaced with a big mangle – wooden rollers approximately 4in in diameter turned by a big wheel (big enough for a five-year-old to sit on and swing). Sheets, pillowslips, and towels were mangled; everything else had to go indoors to be ironed.

When the wash house was not in use (it was only used on Mondays), Uncle used to hang birds on the inside door handle. He got them from a friend’s farm when they went shooting. Quite often these were rooks, and pigeons, and sometimes a jay. I was terrified of them, hanging with their beaks wide, eyes staring and wings flapping open. I had to peep I was so scared, but just could not look. My cousin Beryl, who often stayed, loved them and stroked the feathers, especially the pretty jay.

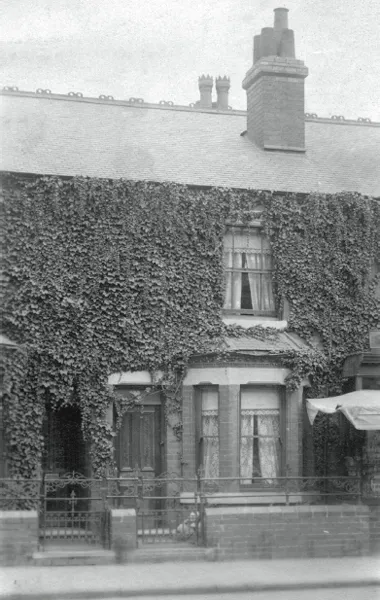

I must introduce myself properly, as an only child called Eveline (Eve to the family; except when I had been naughty – then it was ‘EVE-line!’) The two terraced houses were ours and the fence between was dismantled, so I had two small yards and two small gardens as my own. The big gate at the bottom of the garden was always firmly bolted, as it led to the road. I was strictly forbidden to go out of this gate. It was a promise I always kept, but sometimes circumvented.

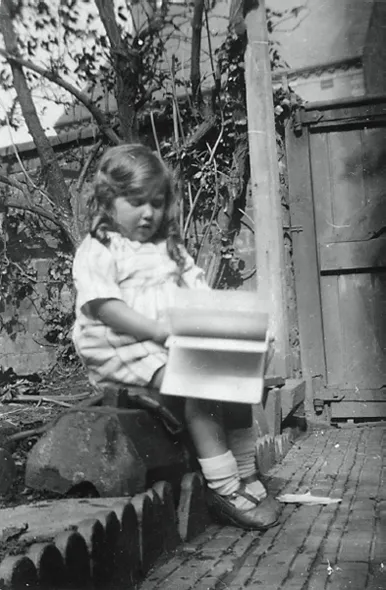

There was the time when I just had to get out, by myself. You see, I had found where the fairies lived, and I wanted to take presents. I knew it was fairyland, a green grassy land with lots of daisies growing. I had discovered it by accident when I was out with my Auntie Flo. We were going through a little alleyway as a short cut, and I got a stone in my shoe. As I bent down, I saw a strange grating in the wall. I peeped in. There it was – fairyland. It was my secret. I just had to take them presents. I made sure that Mum was busy (she helped my Aunt Ada, who was a dressmaker), Aunt Flo was out shopping, Dad was busy in the salon, and Gran was cooking in her kitchen. I was (safely) playing in the yard. On this special day, I had saved some sultanas and sweets. I was determined to take them to the fairies. I could not go out of our gate, but next door’s gate was always open! I clambered over the low fence, and I was out.

Our first house, No. 83 Queens Road.

It was a scary journey. I kept my head down so no one would see me. I had to go about fifty yards along the street, and then cross the main road which was a bus terminal. I waited till two buses went by; they seemed much bigger and noisier than when I was with Mum. Trembling with a mixture of excitement and fear, I got there. Over the cobbles in my alleyway to my grating – the secret door to my magic world. I knelt down and carefully pushed my gifts through the grating, and blew kisses to my fairies. I was very pleased with myself. Then I had to get back; past the people waiting for the buses, wait for the big, red, monster double-decker to go by. What if I can’t get in? What if they have missed me? I realised the enormity of my escapade, and with shaky legs, climbed back. All was well! They thought I was playing with my balls or Teddy and Wollygog, my constant companions!

The forbidden gate.

![]()

2

Sundays

Sundays were special. That was God’s day. Everything stopped. No school, no shops, no buses, only Sunday school and chapel. In the morning, with a bow in my carefully brushed hair, new socks and polished shoes, I went to Sunday school with my Auntie Ada. She was a teacher in the big ones’ Sunday school.

I was four and clutching my pennies for collection. I liked that bit. Each child went to the front and said solemnly, ‘See this little penny, it is brought by me for the little children far across the sea’. Then, I put my penny in the hand of the big Blackman moneybox, and he swallowed it.

The rest of Sunday was boring. No balls, no skipping rope, no books – except the hymn book and Bible – no Rupert, no Tiger Tim. My Mum, Gran and the two aunts were very prim and old fashioned – the chapel meant a lot to them.

Then, it was best clothes and gloves on for a walk with Mum and Dad. If we were lucky, it was the park; but no running about. Just walk properly. It’s Sunday!

One day when I got home, Gran asked me about Sunday school at God’s chapel. I said ‘God wasn’t there today’. Gran was horrified. ‘Of course He was there, it is God’s house. He is always there.’ ‘Well, he didn’t come today,’ I stomped, annoyed that she had not believed me.

It turned out that Mr X, the Sunday school secretary, had not been that day. He was an elderly man with a grey beard, and always wore his black cloak and mortar board. I thought he was God. My Dad was most amused when he found out. Apparently my ‘God’ was very much a man of the world and not always well thought of.

I was puzzled. If he wasn’t God, who was He? Was there really a God? This was a question that has, and still does, puzzle many.

My Gran taught me the Ten Commandments when I was about five. I understood that you must not steal or kill, or say bad words, and must always love Mum and Dad and not keep wanting everything. But when I asked, ‘What is adultery?’, Dad looked up and said to Gran, ‘That’s playing with fire!’ It satisfied me. It meant little girls should never play with matches – only adults do that. So I knew all the Commandments.

‘The Congs’, God’s house.

Sundays meant a posh tea, sandwiches and cake with Gran, and then there was chapel at night with Mum and my aunts. My best behaviour was essential. I hated it.

Then, hair brushed and put in rags (for next day curls), and it was prayers by the side of the bed and goodnight. Pleased that Sunday was over, I curled up in bed ready for school and my friends on Monday.

In 1926 a lady came to our chapel to give a talk about her work as a missionary in Africa. A child from the Sunday school was to present her with a bouquet. I was not at all pleased when I was chosen (Mum and Aunt Ada had a lot to do with that!).

I was to say, ‘We would like you to accept this from the children of the Sunday school’. They made me practise over and over, and when the day came, Mum said, ‘Let’s hear your little speech’. I chanted it twice through. Mum said, ‘Yes, that’s right. Just give a little curtsey and SMILE’ I repeated it sing-song and then added, ‘But you know I am not going to say it’. ‘Don’t be silly’, Mum said, ‘You know you can’.

At the end of the talk Mum and I were waiting with the flowers. ‘Go on’ said Mum. I just stumped up to the lady, thrust the flowers in her hand and said ‘These are for you’. Then I turned and walked off.

All the people there laughed, but it was one of those times when Mum said, ‘EVE-line! You are a naughty girl.’

Sunday walks were always so formal; dressed up in ‘Sunday best’ and walking ‘properly’. One short walk was to the park. Riversley Park had been donated to the town by Alderman Melly, and on Sundays the brass band played to crowds of people from the specially-built bandstand (which is still there). Mother loved this. I was bored, standing still, just listening. The best part of that walk was feeding the ducks from the little bridge over the river.

Mum, a friend, Miriam, and myself on a summer’s day in Riversley Park.

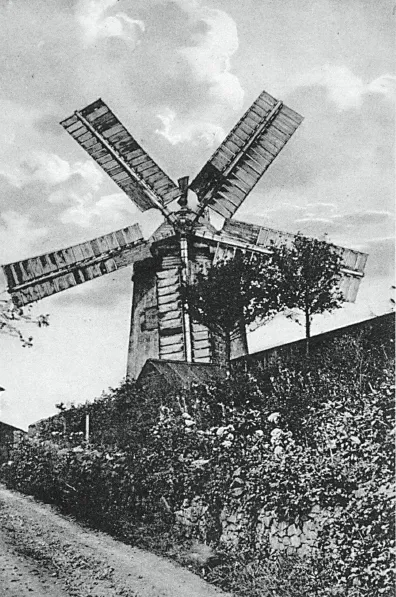

The windmill at the top of Tuttle Hill, Nuneaton.

On sunny days we sometimes went on a really long walk, about four miles. I liked it because we went to see the windmill at Tuttle Hill by the big quarry. It was huge and had five sails which sometimes turned in the wind. Then through the fields (now Camp Hill Estate) to Buck’s Hill where a farmer kept goats. I had a cup of goat’s milk which I did not like, but drank because it was to make me clever. Then, after that long walk, we went home by bus; that was extra special, and made it by far my favourite walk. A few years later we read ‘The Windmill’ by Longfellow – it was almost as if it was my poem about my windmill.

![]()

3

Gran’s Stories

My Gran often told me stories of her family. She told me how her husband had been called John and it was his shop. When he died she was very sad, and so were her children (who were not much older than me). ‘What about the shop?’ I asked.

Gran told me that she had advertised and had chosen Dad from the three men who had applied for the job. He lived with them and that’s how he became friends with Annie, my Mum.

She told me how they lived in Chapel Street when Victoria was Queen in the 1860s. She had two sisters, Emma and Ada, and a brother, George. Her father was called Mr Wykes. He was a nail maker and had a workshop at the end of his garden.

He employed another man and together they made nails by hand. Each nail was made separately from a thin rod of iron. I was surprised when she told me of so many different sorts.

Sprigs were tiny nails used to repair shoes so that they would not stick in your feet. Tacks were small and sharp, used for upholstery (chairs she explained), brads had small heads for floors and ceilings. The miners’ boots had hobnails, they had big flat heads, and 1in, 2in, 3in, and 6in for builders. Sometimes there was a special order for triangular nails for climbing boots. So many nails!

Machines were being invented that made nails much more quickly, so they were cheaper. As his trade began to suffer, and he found it hard to pay the man’s wages, Eliza and Emma (Gran and her sister) were sent with a big bag of potatoes from their garden to help the man’s family, as food was so short.

I learned how her Mother (also Eliza) had come from Bideford in Devon to be a governess to the children of the Baker family. They were chemists in Abbey Street, Nuneaton.

She had met John Wykes at the Congregational chapel. Gran told me how her Mother would have liked to go back to see her old home and family, but it was much too far, more than 100 miles. So it was much too expensive and would take too long. I thought it was sad that she never saw her parents again. I would not like that.

When Gran grew up she met another John, this time John Hatton, at the chapel. They got married and lived further up Chapel Street. Her children, my Mum, Aunties Ada and Flo and my Uncle Will were all born there. They had a pony and trap with a stable where the pony, called Polly, lived.

By the time they were grown up, Gran’s Dad had no work. Machines now meant that individual nail making was no longer needed.

I knew Uncle George. George was now a master builder and he employed his father. He lived in the house next door. I did not like him. He was rough. He did not like me. He called me ‘That spoilt brat’.

Gran explained to me that he had had a sad life. When he was a successful builder, he built a row of houses in John Street, and others in Pool Bank Street. He built a special house for himself and his family in Tuttle Hil...