![]()

1

THE PATH TO THE SPITFIRE

The year 1931 saw the Supermarine Aircraft Works at Southampton riding the crest of a wave, firmly established as a world leader in the design and production of high-speed racing seaplanes. In September of that year the Supermarine S.6B won the coveted Schneider Trophy outright for Britain, with a flight round the circular course at an average speed of 340mph. A few months later a sister aircraft advanced the world absolute speed record to 379mph. Later still in that same year, an S.6B with a modified Rolls-Royce R engine raised the world absolute speed record to 407mph. To realise any of those feats in a single year would have been a magnificent achievement for any aviation company, but to accomplish all three was an absolute triumph for Supermarine and its talented Chief Designer, Reginald Mitchell.

Yet although the design and production of the racing floatplanes had advanced the cause of high-speed flight, it would take some years before the various lessons could be incorporated in service equipment for the RAF. The racing seaplanes had been tailor-made to perform one specific task – achieving the highest possible speed over the measured course, and alighting on the water safely afterwards. Little else mattered. These aircraft had short endurance, poor manoeuvrability and very poor visibility for the pilot in his cramped cockpit. Also, since the RAF had won the Schneider Trophy outright, there was no chance of anyone else running a challenge in the foreseeable future.

After the excitements of the previous year, the focus of the company’s workforce returned to the production of the Southampton, Scapa and Stranraer twin-engined, long-range maritime patrol flying boats, to meet orders for the RAF and foreign air forces. Also in the autumn of 1931, and with a good deal less fanfare than had attended the activities of the racing floatplanes earlier in the year, the Air Ministry in London issued Specification F.7/30 for a new fighter type to equip its home defence squadrons. At that time the fastest fighter in the RAF inventory was the Hawker Fury, a biplane with a maximum speed of 207mph. As aviation experts pointed out, when the Fury reached its maximum speed in level flight it was flying at barely half as fast as the Supermarine S.6B had gone during its final record-breaking run.

Those who drafted the specification for the new fighter did not specify exact performance or other requirements. Instead, the various design teams were told to meet certain minimum requirements and do the best they could offer in terms of speed. The F.7/30 laid down the following requirements for the new fighter:

The highest possible rate of climb

The highest possible speed above 15,000 feet (ft)

A good view for the pilot, particularly during combat

Good manoeuvrability

Be capable of easy and rapid production in quantity

Ease of maintenance

An armament of four .303 inch (in) machine guns and provision to carry four 20 pound (lb) bombs.

When specification F.7/30 was issued, Great Britain was in the grip of a financial slump. Times were hard for the nation’s industries, and none more so than the aviation industry. There was intense competition to secure what might prove to be a lucrative order from the RAF, and perhaps foreign governments as well. Seven aircraft companies submitted design proposals for eight fighter prototypes to meet the F.7/30 requirement. Five of the aircraft were biplanes: the Bristol 123, the Hawker PV3, the Westland PV4, the Blackburn F.7/30 and the Gloster SS37. The other three entries were monoplane designs: the Vickers Jockey, the Bristol Type 133 and the Supermarine Type 224.

At that time the most powerful British aero engine available for installation in fighters was the Rolls-Royce Goshawk inline, which generated 660 horsepower (hp). On that power no aircraft was going to go much faster than 250mph, and at that speed the advantage of the monoplane over the biplane was by no means certain. Indeed, the consensus amongst the leading British designers at that time was that the biplane was slightly the better, as was shown by the greater proportion of biplanes entered for the F.7/30 competition (five against three). In the all-important matter of rate-of-climb, a good biplane would usually show a clean pair of heels to a good monoplane, and it was considerably more manoeuvrable.

The Supermarine 224 was Reginald Mitchell’s first attempt to build a fighter aircraft, for his entry in the F.7/30 design competition. Although the Type 224 was roundly defeated in that contest, it would serve as a vitally important stepping stone to the aircraft that later became the Spitfire.

The Supermarine submission to the competition was an all-metal monoplane designated the Type 224. Power was from a Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine developing 660hp. The Type 224 made its first flight in February 1934, when it demonstrated a top speed of 238mph and took eight minutes to climb to 15,000ft. The engine employed an evaporative cooling system, using the entire leading edge of both wings as a condenser to convert the steam back into water. However, the system did not work well, and when the pilot ran it at full throttle for any length of time the engine was liable to overheat. Flight Lieutenant (later Group Captain) Hugh Wilson was one of the RAF pilots who tested the aircraft. He told the author: ‘We were told that when a red light came on in the cockpit, the engine was overheating. But the trouble was that just about every time you took off that red light came on – it was always overheating!’

If the aircraft was to make a combat climb at full throttle, when it reached 15,000ft the condenser in each wing would be full of steam. Then the relief valve at each wing would open, and a line of excess steam would trail behind each wing. Once that happened the pilot had to ease back on the throttle and level the aircraft, to allow the engine time to cool down before he could resume his climb. For an aircraft intended to go into action at the end of a rapid climb, the requirement to level off to cool the engine would have been be a major limitation in combat. Even when it sat on the ground the Type 224 made enemies, as ground crewmen soon learned the folly of resting a hand on the steam condenser in either wing before it had cooled down after a flight.

The Type 224 did not show up well against its competitors, either. The winner of the F.7/30 competition was a biplane of conventional layout, the Gloster SS.37. It had a maximum speed of 242mph, giving it a small advantage over the Supermarine Type 224, but for its time the Gloster fighter possessed a superb rate of climb: it reached 15,000ft in six and a half minutes – a full one and half minutes ahead of the Supermarine design. Moreover, it was a far more manoeuvrable than the Type 224. The SS.37, with modifications, would enter RAF service later in the decade as the Gladiator.

Beverley Shenstone joined the Supermarine design team as an aerodynamicist in 1934, by which time the Type 224 was of no further interest either to the RAF or to Supermarine. During a discussion of the Type 224 with the author, Shenstone commented:

When I joined Supermarine, the design of the Type 224 was virtually complete and I had little to do with it. As is now well known, that fighter was not successful. My personal feeling is that the design team had done so well with the S.5 and the S.6 racing floatplanes, which in the end reached speeds of over 400 mph, that they thought it would be child’s play to design a fighter intended to fly at little over half that speed. They never made that mistake again!

Towards the end of 1934, Rolls-Royce began bench testing a new 27 litre (l) V-12 engine designated the PV XII (later named the Merlin). It passed its 100-hour type test while running at 790hp at 12,000ft, and aimed at an eventual planned output of 1,000hp. In November 1934 the board of Vickers, the parent company of Supermarine, allocated funds for Mitchell and his team to commence preliminary design work on a completely new fighter powered by the PV XII engine. The proposal aroused immediate interest at the Air Ministry, and in the following month the company received a contract to build a prototype fighter to the proposed new design from Supermarine. The new fighter received the designation F.37/34.

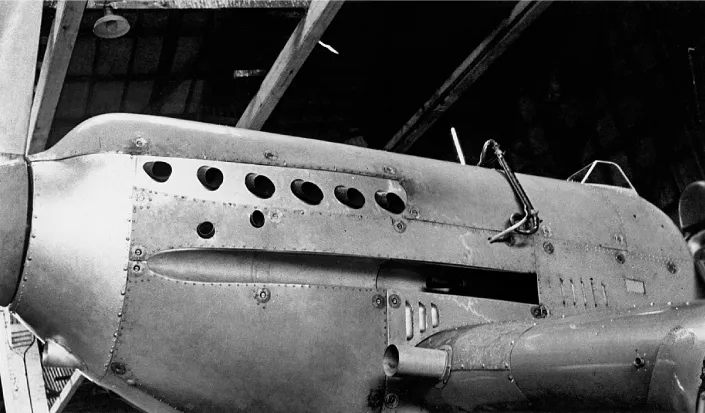

Close-up of the Type 224, showing the relatively high drag method of construction used in this aircraft.

The incorporation of the new Rolls-Royce engine into the proposed new Supermarine fighter opened up an entirely new range of performance possibilities for the new machine. With speeds well over 300mph now in prospect, Mitchell could use his hard-won experience in drag reduction in high-speed aircraft. Nevertheless, it was first necessary to make some changes to the airframe to enable it to accommodate the new engine. The PV XII engine weighed about one-third more than the Rolls-Royce Goshawk engine it was to replace, so to compensate for the forward shift of the centre of gravity, the sweepback of the leading edge wing had to be reduced. From there it was a relatively minor step to incorporate the elliptical wing that would be the most recognisable feature of the new fighter. Beverley Shenstone told the author about the process by which this change came about:

The elliptical wing was decided upon quite early on. Aerodynamically it was the best for our purpose because the induced drag, that which is caused in producing lift, was the lowest when this shape was used: the ellipse was an ideal shape, theoretically a perfection. There were other advantages so far as we were concerned. To reduce drag we wanted the lowest possible wing thickness-to-chord ratio, consistent with the necessary strength. But near the root, the wing had to be thick enough to accommodate the retracted undercarriage and the guns; so to achieve a good thickness-to-chord ratio we wanted the wing to have a wide chord near the root. A straight-tapered wing starts to reduce in chord from the moment it leaves the root; an elliptical wing, on the other hand, tapers only very slowly at first, then progressively more rapidly towards the tip... The ellipse was simply the shape that allowed us to carry the thinnest possible wing, with sufficient room inside to carry the necessary structure and the things we wanted to cram in. And it looked nice.

The F.37/34 prototype K5054 pictured at Eastleigh Airfield, Southampton, on 5 March 1936, shortly before it took off on its maiden flight.

At this time most major air forces – the Royal Air Force included – operated fabric-covered biplane fighters with open cockpits and fixed undercarriages. Compared with that, the new Supermarine fighter was a revelation: a cantilever monoplane constructed almost entirely of metal, with a supercharged engine, an enclosed cockpit and a retractable undercarriage.

The overwhelming credit for the fighter now taking shape in the drawing office at Woolston must of course go to Reginald Mitchell and his small design team, and the Rolls-Royce engineers at Derby struggling to improve the power output and reliability of the PV XII engine. Yet there were others, some working for the government, who also deserve a share of the credit.

One of the few design stipulations in the F.7/30 specification was that the armament should comprise four Vickers .303in machine guns. Squadron Leader Ralph Sorley, working at the Operational Requirements section at the Air Ministry, cast doubt on that score. He argued that the four Vickers .303in machine guns, each firing at a rate of 850 rounds per minute (rpm), would lack the punch to destroy the fast all-metal bombers then about to enter service in the major air forces. Sorley, an experienced military pilot, believed that in any further conflict fighter pilots would find it extremely difficult to hold their gun sight on a high-speed bomber for more than a couple of seconds. Unless a lethal blow could be administered in that time, the bomber would escape. Sorley later wrote:

By 1934 a new Browning gun was at last being tested in Britain which offered a higher rate of fire [1,100rpm]. After much arithmetic, I reached the answer of eight [Browning guns] as being the number required to inflict the required two-second burst. I reckoned that the bomber’s speed would probably be such as to allow a pursuing fighter just one chance to attack, so the bomber had to be destroyed in that vital two-second burst.

Sorley’s arguments convinced the Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, Air Vice-Marshal Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, that the new fighter would need to carry eight of the new rapid-firing Browning guns, rather than four slow-firing Vickers guns. In April 1935 Sorley visited the Supermarine works to ask whether there was room in the wings of the new fighter to accommodate the revised armament. Mitchell passed the question round his design team and the answer came back in the affirmative: it would indeed be possible to fit the additional four guns into the fighter’s wings.

By mid-1935 the main design parameters for the revised fighter had largely been settled, and metal was being cut. However, there remained one important aspect: how to cool the PV XII engine. The initial thought was that the evaporative cooling system should be retained, despite its miserable performance when fitted to the Goshawk engine of the Type 224. The alternative, to use a conventional cooling system with external radiators, would impose a severe drag penalty.

Selecting an effective method for cooling the engine was no trivial matter. When the PV XII ran at full power, it produced an amount of heat roughly equivalent to 400 1-kilowatt electric fires running simultaneously. Unless that heat could be dissipated, the engine would overheat and was liable to suffer damage. Fortunately, Fred Meredith, a scientist working at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, had been experimenting with a novel t...