![]()

1

KENSINGTON

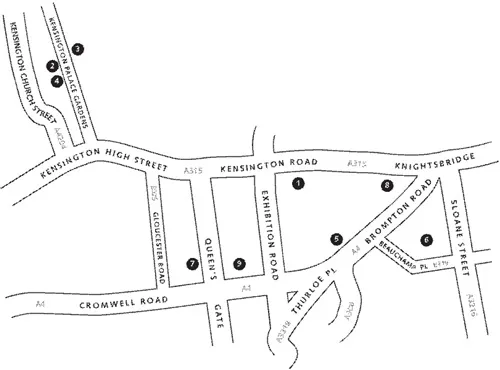

The Kensington area is centred on Kensington Gardens to the west of Hyde Park. Most of the buildings of interest can be found in Kensington Palace Gardens to the west and then south of the park around Knightsbridge. Wormwood Scrubs Prison lies just outside the borough of Kensington and Chelsea’s northern edge.

The whole area has a surprising past, much more than might be expected with the association with high-class shopping. From the abandoned Underground station of Brompton Road to secret training schools and research departments, there is a lot more to Kensington than just its famous department stores and restaurants.

The most well-known area of Kensington is probably Knightsbridge, where Harrods and Harvey Nichols can be found. But, little known at the time, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, more commonly known as MI6) had set up training schools for their radio operators and Norwegian agents in the area, while SOE had a photographic section in Trevor Square, a short walk from Harrods. A little further down the Brompton Road, the Underground station by the same name was being used as an anti-aircraft division’s control room.

Kensington is able to boast one of the most exclusive streets in London: Kensington Palace Gardens, otherwise known as Palace Green. Several buildings down here are official ambassador residences, most notably those of Norway and Russia, while numbers 6 to 8 had a murkier past as a prisoner interrogation centre where the methods used might perhaps be compared to those of the Gestapo. You may walk up and down this boulevard, but be careful to keep your camera in your bag as there is a strict prohibition on photography. Sections of SOE also found premises in this area, with the camouflage section starting out in the building adjacent to the Natural History Museum, which itself had a demonstration room for dignitaries.

KEY

1. Norwegian Government in Exile

2. Norwegian Ambassador’s Residence

3. Residence of the Soviet Union Ambassador to Great Britain

4. The London Cage, MI9 Interrogation Centre

5. SIS, Norwegian Training School

6. SIS, Communications Section VIII

7. SOE Camouflage Section, XVa

8. SOE Photographic and Make-Up Section, XVc

9. SOE Demonstration Room

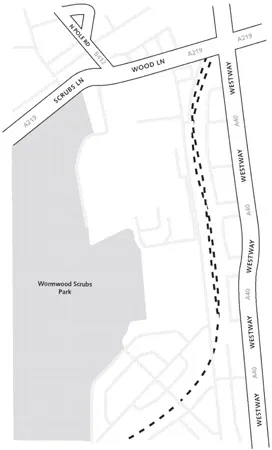

MI5 HQ, Wormwood Scrubs, 1939–40

DU CANE ROAD

Tube: East Acton

Barclays Cycle Hire: None close

Wormwood Scrubs Prison, with its distinctive gatehouse, can be found on DU CANE ROAD on the south side of Wormwood Scrubs Park, which is on the north-west corner, but just outside of the borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Wormwood Scrubs is still in operation today as a Category B prison, with an operational capacity of nearly 1,300 prisoners.

The Security Service, more commonly known as MI5, has been in existence since 1909, when it was formed as the Secret Service Bureau, which effectively incorporated both MI5 and SIS (usually referred to as MI6). The following year they separated into the two organisations we know today, with MI5 being responsible for all ‘home work’, including espionage and counter-espionage with Vernon Kell as its chief. SIS was then responsible for all foreign intelligence, with Mansfield Cumming as its chief.

Up to the outbreak of the Second World War, MI5’s offices could be found (albeit by very few people) on the top floor of Thames House, Millbank. On 27 August 1939, with the onset of war, Kell, who was still head of MI5 at the age of 66, moved the service from Thames House to Wormwood Scrubs due to an urgent need for more space to carry out wartime work.

By January 1940 the service had grown to 102 officers from just three in July 1939, and continued to grow as the War Cabinet passed an act allowing the internment of anyone believed to be sympathetic to foreign powers. This act resulted in 22,000 Germans and 4,000 Italians being interned, along with 753 members of the British Union of Fascists.

One of the more notable new arrivals at MI5 was Victor Rothschild, who secretly retrieved bomb fuses for research from the Continent and created a counter-sabotage department in one of the cells. Rothschild seemed to enjoy defusing German bombs, such as the one which was hidden in a crate of onions from Spain timed to explode in a British port.

But all was not well with MI5 in its prison home as the Scrubs was not the best working environment. Staff using cells as offices had the alarming possibility of getting locked in due to the obvious lack of a handle on the inside. Meanwhile in official circles, the service was seen as a ‘chaotic’ organisation that Kell had lost control of. On 10 June 1940, Kell was removed from office (dying in March 1942) to be replaced by Jasper Harker of B Branch (at that time responsible for counter-espionage). Harker did not last very long and, after he had carried out an audit of MI5 which concluded ‘that the Service had suffered from poor management and planning which had led to organisational breakdown and confusion’, was replaced by Sir David Petrie in 1941.

However, Harker was in charge long enough to oversee the move from prison to palace in October 1940, when the greater part of MI5 was moved from the Scrubs to Blenheim Palace – Churchill’s childhood home – after it was concluded that the prison did not offer the protection required. As the Blitz intensified, only the ground-floor offices were thought to be ‘reasonably safe’, while many of the staff on the upper floors had to vacate their rooms. The Registry, which was the filing system of the organisation where the details of people under investigation were recorded and could be cross-checked, was not as sheltered as it should have been. Unfortunately the decision to locate the Registry in a glass-roofed workshop was proven to be a poor one when a September 1940 bombing raid damaged the prison and much of the Registry was lost to fire or the subsequent water damage caused in dampening the flames.

After the move, some of MI5’s staff did remain in London, but not at the Scrubs; they moved into offices at 58 St James Street. Today MI5 can be found back at Thames House at Millbank again.

Norwegian Government in Exile

KINGSTON HOUSE NORTH, KENSINGTON ROAD

Tube: Knightsbridge

Barclays Cycle Hire: Exhibition Road, South Kensington

KINGSTON HOUSE NORTH, the home of the Norwegian government in exile after Norway fell to the Nazis, can be found just off Kensington Road on the south side of Hyde Park. The building has a green plaque, unveiled on 27 September 2005, acknowledging its wartime use.

The Scandinavian countries were in a difficult position come the onset of the Second World War. None were in a position to repel any hostile advance for any length of time and therefore had to decide on their political stance with care. Sweden had the closest ties with Germany and managed to remain neutral throughout the war. Meanwhile, Finland had greater issues to consider since it was soon fighting off a Soviet onslaught on its border.

Norway, like Sweden and Denmark, chose to adopt a position of neutrality. While the government’s sympathies lay with the Allies, it was made clear by Hitler that Germany would not tolerate a neutral Norway in name that was in fact aiding the Allies. Meanwhile, Britain had secured the charter of much of the Norwegian Merchant Fleet on 11 November 1939, but Norway also signed an agreement to maintain exports at 1938 levels with Germany.

Churchill was soon to become obsessed with Norway and advocated the mining of Norwegian territorial waters to prevent iron ore shipments. This in turn led to a plan to occupy Narvik and other mining districts in Norway. By April 1940, the situation had developed with both the Germans and British repeatedly breaching Norway’s neutrality by entering her waters. Eventually the Allies decided they could wait no longer and put in motion their plan to land troops in Norway.

The green plaque on Kingston House North, marking its use by the Norwegian government.

The embarkation of British, French and Polish troops destined for Narvik coincided with German plans for Norway. Hitler’s position at the onset of war was that a neutral Scandinavia was in Germany’s best interests, but events changed this view. This was in part due to repeated Allied violations in Norway and the risk posed to Germany of Britain establishing bases in Norway itself. The petitioning from his advisors was also a factor; especially those from the navy who pointed out that the extensive Norwegian coastline offered much greater access for their ships to the North Sea.

In the event, bold German plans to invade were put into action on 8–9 April 1940, when they swiftly overcame the Norwegian forces, which had been in decline since the First World War. The only significant success for Norway came when a coastal fort sank Blücher, a recently commissioned troopship, with the loss of over 1,000 German soldiers.

The Norwegian government’s reaction was confused and haphazard to say the least. When King Haakon VII was told that the country was at war, his reply was ‘with whom?’ since it had been considered a distinct possibility that it would be Britain who would be the aggressor. As it transpired, the only significant decision taken was to ask Britain for assistance, which was given forthwith.

No decisive action was taken regarding the mobilisation of the Norwegian armed forces, which was given by mail on 12 April, delaying the formation of their army. However, the Norwegians, supported by Allied forces, fought on for sixty-two days before departing for Britain. The outcome may well have been entirely different had the warning signs of a German invasion been acted on and, once committed, Allied efforts had been better co-ordinated.

On arrival in London, the Norwegian government took out leases on most of the flats in Kingston House North. All aspects of the government were run from these offices, including the Defence Staff, the Central Bank and the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Meanwhile, back in Norway, the Germans were able to look back on a stunning victory, which had by no means been certain. They now controlled Norway via the puppet Quisling government, which secured Norway’s iron ore deposits and gave them unhindered access to the North Sea and the Atlantic beyond. A German, rather than British, presence in Norway also removed any chance of Sweden entering the Allied cause and prevented t...