- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Story of Durham

About this book

The Story of Durham traces the evolution of a city that medieval writers likened to Jerusalem, which Ruskin termed one of the wonders of the world, and which Pevsner, more modestly, called one of the architectural experiences of Europe.

To Bill Bryson, meanwhile, Durham appeared 'a perfect little city' with 'the best cathedral on planet Earth'. The city is a physical manifestation of a significant event in our history: the Romanesque cathedral and castle together constitute this country's monument to the Norman invasion, the last of our country.

Beautifully illustrated, this popular history by a leading academic will delight residents and visitors alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Story of Durham by Douglas Pocock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

seven

VICTORIAN DURHAM

Victorian Durham participated only modestly in the unprecedented population growth and feverish industrial expansion of the nineteenth century. Population census figures summarise the justification for such a statement, for while the county’s total increased tenfold during the century the city’s figure little more than doubled. In terms of settlement totals, the city in 1801 had only recently conceded first place in the county to Sunderland, but by the end of the century, although its population had reached 16,000, it had slipped to twelfth position. Industrial-urban growth along the river estuaries of the Tyne and Tees across the county boundary put its regional ranking in even poorer light.

The lack of any large-scale industrial activity may be attributed to an absence of level sites with access to water transport, together with late and circuitous connections to the rail network as a result of topographical and land-ownership difficulties. Thus, while many Victorian cities grew dramatically as a result of focusing on a single industry, Durham continued to evolve as a multifunctional settlement, albeit that several of its activities and roles were relatively modest.

A Railway Town

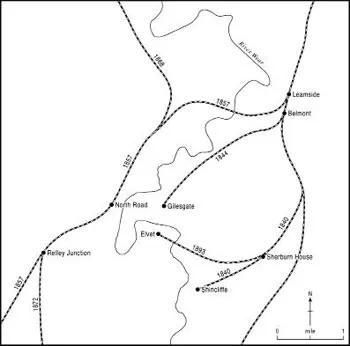

Although County Durham saw the birth of railways, the single most potent symbol of vitality in Victorian England, it was almost half a century later before the county town was to achieve direct access to London. The city even possessed three railway stations, but none provided the impetus for commercial growth. Perhaps growth would have been encouraged by the level terrain beyond the head of Old Elvet had the Sunderland and Durham Railway not encountered ecclesiastical opposition in the 1830s to its wishes for a terminal at Elvet. Instead, the line from Sherburn House had to terminate at Shincliffe village 1½ miles south-east of Durham.

55 Arrival of the railway.

A line was eventually brought in, but not until 1893 following a City Council petition to the directors of the North Eastern Railway, (55) but by then opportunities had been exploited and patterns set, such that it was surely difficult to conceive where sufficient potential traffic, passenger or goods, was to be generated.1

The city’s first station was that at Gilesgate, beyond the top of Claypath, in 1844. It was the terminus of a branch line from Belmont (‘Durham Junction’) of the Newcastle and Durham Junction company. Strangely, the arrival of the iron horse in town received no comment from the local Durham Advertiser. The station building itself was of stone in an elegant Georgian style by J.T. Andrews. The main route from York to Newcastle had bypassed Durham to the east; Belmont, 2½ miles to the north-east, was the nearest point to the city. George Hudson, known as the ‘Railway King’, had largely pioneered the east coast route, so that it is instructive to note his comment in the Advertiser on the difficulties he encountered with the major landowners:

It is always unpleasant to come into contact with so influential and so important a body. The Dean and Chapter professed to be willing to meet this company on liberal terms, but he could not but say that the professions they made and the conduct that they subsequently exhibited were perfectly irreconcilable.2

The whole line became known as the North Eastern Railway in 1854 as a result of an amalgamation of companies.

The city’s North Road station opened in 1857. Northward, its rail joined the main line at Leamside, just a mile from Belmont, which it superseded. It required an impressive viaduct over the Wear gorge downriver from Kepier. Southwards, the line went as far as Bishop Auckland, beginning with an even more impressive viaduct. The station itself was a dignified, if modest, construction in stone designed by T. Prosser in Tudoresque style, complete with arches and battlements.

Although only on a branch line within County Durham, the celebration of its opening contrasted markedly with that thirteen years earlier at Gilesgate. Realisation of the prosperity that railways could bring – and had brought to other towns – was doubtless a key factor. Moreover, the station was both prominently sited, unlike Gilesgate’s which was half-hidden, and alongside a spectacular curving viaduct of eleven arches. The latter was Durham’s contribution to an age noted for its towering monuments, and was by far the biggest piece of construction in the city since the Norman cathedral. On 1 April 1857 crowds gathered at the decorated station and adjacent slopes to greet the first train, which was carrying NER directors and guests from Leamside. Its arrival was met by the mayor and a salute of cannon. The train then pulled out over the viaduct to a salvo of artillery from the grounds of Mr John Lloyd Wharton of Dryburn Hall. Having reached Bishop Auckland, they soon returned, to be greeted this time by the Durham City Band and a champagne luncheon in the town hall.

56 Railway viaduct under construction, 1856.

57 Embankment for the viaduct under construction, 1855.

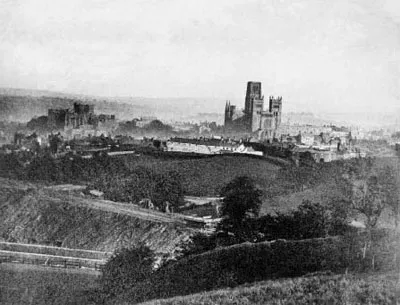

The advent of the railway in general and the viaduct in particular markedly changed the appearance of the edge of the western rim of the bowl in which the city lies. The viaduct represented a massive engineering feat, achieved by NER’s own engineers, Richard Cail and Thomas Harrison. The wide opening into Flass Vale, the source of the Mill Burn, was alternately marsh or peat bog, such that tree trunks had to be sunk up to 50ft depth to give stability to the 100ft high pillars. (56) The total span of some 280yds would have been more but for an embankment built out into the Vale of sand and clay excavated from a 90ft cutting at Redhills, (57) part of the north-south ridge that had been the site of the Battle of Neville’s Cross. For rail travellers journeying north, the effect of the cutting was to produce a suddenness in the appearance of the spectacular scene of cathedral and castle, surely the most famous carriage window view in England. John Ruskin, who declared the view from just above the station one of the wonders of the world, was among the early visitors to appreciate the newly provided vantage point. It is said Queen Victoria would order her train to slow to take full advantage of the view while crossing the viaduct.

Durham eventually assumed its rightful place on the main line between London and Scotland when its North Road station was linked directly north by a line from Newcastle along the Team Valley to Newton Hall in 1868, followed in 1872 by a southern line laid from just beyond the Neville’s Cross ridge at Relly Junction to link with the early main line route at Tursdale.

Coal Mining

Although the Victorian city found itself in the middle of the evolving Durham coalfield, the county town did not become a coal capital. Early patterns of exploitation had already been established in the north and north-east of the county, along the incised valleys of the lower Wear and Tyne, to which wooden wagonways further channelled exports of so-called ‘sea coal’. Several of the exporting centres then became rail foci, which in turn encouraged the assembly of materials and the emergence of secondary industries. Differential fortunes, however, were not always appreciated by many elsewhere, who perceived the nineteenth-century city and county as one. A good example is the admission of Matthew Arnold who, on his travels from the south in 1861, had to admit to surprise at what he saw: ‘the view of the cathedral and castle together is superb; even Oxford has no view to compare with it … I was most agreeably disappointed, for I had fancied Durham rising out of a cinder bed’.3

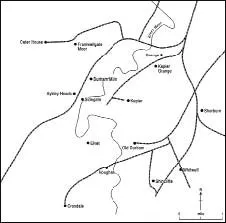

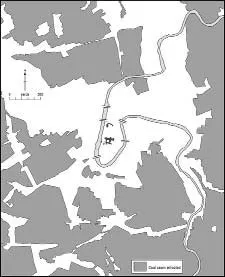

While Durham did not become a centre of coal mining, it was nevertheless surrounded by mining activity as dozens of shafts were sunk and colliery branch lines criss-crossed the area. (58) The peak of activity in the vicinity of the city was in the 1860s and 1870s as the focus of nineteenth-century mining in the county moved slowly from west to east, having begun on the exposed part of the field and been worked increasingly towards the coast, with the eastward-dipping seams requiring ever deeper shafts.

58 Nineteenth-century collieries and colliery railways in the vicinity of Durham.

Geological conditions within the eastward-dipping seams varied, such that the number and thickness of coal seams was the outcome of conditions during deposition and on subsequent geological history. In the Durham area, for instance, of the five workable seams only three were present to the east of the city. Thus, while the Hutton seam was widely extracted in the area, the pattern of working of the lower Busty seam stopped abruptly east of the city. (59, 60) Both maps well illustrate the extensive nature of extraction, being the collective underground work of the many collieries shown in the earlier map. The boundaries of colliery leases are clearly decipherable.

59 Coal extraction from the Hutton seam in the vicinity of Durham.

A more local variation underlies the lack of exploitation beneath the peninsula, where, even if the authorities had given permission for working, efforts would have been thwarted. Here, during a glacial period, the Wear was aligned to a much lower sea-level and consequently deeply incised its bed, well below the present. Despite subsequent infilling in post-glacial times, the buried river bed presented insurmountable drainage problems to any would-be extraction. Thus, the river gorge, which played a key role in the defence of the early city against Vikings and the Scots, performed a much later protective role in warding off an underground attack.

The era of shaft mining in the city, as opposed to shallow bell pits, began in 1828 with the sinking of Elvet colliery. (61) Most of the larger pits followed a decade or more later, with Framwellgate Moor (opened 1841) and Old Durham (1849) the two biggest. Both were worked by the Marchioness of Londonderry, the first leased and the second owned, and were the only two pits to have coke ovens attached. They also had by far the largest number of tied cottages, more than 180 at Framwellgate Moor and 250 on Gilesgate Moor in a compact series of streets called New Durham.4

By mid-century almost 700 mineworkers were living in the city, barely one-tenth of whom had been born in Durham. The bulk were immigrants from elsewhere in the North East, with the remainder from other mining districts, as well as some Irish immigrants. During the second half of the century the number of mineworkers doubled – during periods of full employment, that is. A pit such as Elvet colliery, which produced only household coal and was therefore limited to a single market, could also vary i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction and Acknowledgements

- One Beginnings

- Two Anglo-Norman Durham

- Three Medieval Durham

- Four Durham Reformed

- Five Eighteenth-century Durham

- Six Early Nineteenth-century Durham

- Seven Victorian Durham

- Eight Durham in Depression

- Nine Durham Resurgent

- Ten A World Heritage Site

- Eleven Durham Distilled

- Twelve The Futures of Durham

- Select Bibliography

- Copyright