eBook - ePub

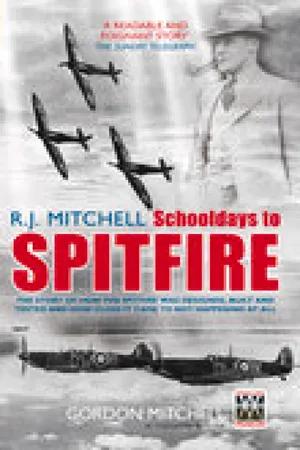

R.J. Mitchell: Schooldays to Spitfire

The Story of How the Spitfire Was Designed, Built and Tested and How Close it Came to Not Happening at All

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

R.J. Mitchell: Schooldays to Spitfire

The Story of How the Spitfire Was Designed, Built and Tested and How Close it Came to Not Happening at All

About this book

The Spitfire began as a near disaster. The developments of this famous aircraft took it from uncompromising beginnings to become the legendary last memorial to a great man - an elegant and, with its pilots, a highly effective, weapon of war. The Spitfire would not have happened at all, however, without Mitchell's indomitable courage and determination in the face of severe physical and psychological adversity resulting from cancer. His contribution to the Battle of Britain, and thereafter to the achievement of final victory in 1945, was so great that our debt to him can never be repaid. This poignant story is written from a uniquely personal viewpoint by his son, Gordon Mitchell.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access R.J. Mitchell: Schooldays to Spitfire by Gordon Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

R.J. Mitchell

‘He’s mad about aeroplanes.’ That is what the Hanley High School boys said about their friend, Reg Mitchell. Yet, when Reg was born, the aeroplane had not been invented. There had been many experiments with balloons and gliders as men struggled to launch themselves into the air. In 1783 the first successful manned flight was made over Paris in a Montgolfier hot air balloon, and just over 100 years later a German, Otto Lilienthal, flew in a hang-glider. In England, most Victorians laughed at the idea of a flying machine. They said: ‘If God had meant men to fly he would have given them wings.’ It is all the more surprising that a boy born in such an age would one day design an aircraft able to fly at more than 400 mph.

Reg Mitchell was born on 20 May 1895, at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, Stoke-on-Trent, where his father, Herbert Mitchell, was a headmaster in Longton. Within a few months of his birth the family moved to 87 Chaplin Road, Normacot, near Longton, not far from the centre of Stoke-on-Trent. Later they settled down in nearby Victoria Cottage, a comfortable house well outside the industrial smoke and clatter of the Pottery Towns.

Herbert Mitchell, a Yorkshire man from Holmfirth, had trained as a teacher at York College. After obtaining a headship in Longton, he married Elizabeth Jane, daughter of William Brain, a Master Cooper of Longton. During this time he established printing classes in the Potteries. Soon after moving to Normacot, Herbert Mitchell gave up teaching and became a Master Printer at the firm of Wood, Mitchell & Co. Ltd of Hanley. By hard work and use of his artistic ability he became managing director and eventually the sole owner of the printing works until his death in 1933 at the age of sixty-eight. He played a very active part in Freemasonry and achieved high office in the fraternity.

In the early years of this century, school teachers, and even headmasters, were very poorly paid, so it was probably his high position at Hanley printing works which enabled Herbert Mitchell to live at Victoria Cottage and support his rapidly growing family. Before long there were five children, Hilda the eldest, and then Reg, Eric, Doris and Billy, all born fairly close to each other, so that Mrs Mitchell had her hands full looking after her family and home.

Victoria Cottage in no way resembled a cottage; it was in fact a very pleasant residence, and provided the sort of comfortable surroundings in which the Mitchell children grew up. The house was quite large, with a dining room and drawing room facing the garden. At the back, there was a large kitchen with a black-leaded cooking range and an even larger scullery used for the rougher kind of domestic work. In common with most houses built at that time, Victoria Cottage had both front and back stairs. Mrs Mitchell always kept a maid to assist her with the housework and care of the children, and the back stairs were reserved for the use of the maid. In the Edwardian period, maids were not allowed to retire to bed by way of the carpeted front stairs used by their employers.

The house stood in its own grounds, with a lawn and garden which gave the children plenty of space to romp and play, free from too much adult supervision. Beyond the garden was a coachhouse and stables; but since no coach or horses were kept, these outbuildings were given over to the children for use as playrooms. Mr Mitchell senior was a firm believer in keeping boys out of mischief by providing them with plenty to keep them occupied. He was also very anxious that they should all learn to use their hands. Reg, Eric and Billy were given tools and simple materials, and encouraged to follow their own hobbies and make things for themselves. But whatever task they started it had to be done properly, since their father was a stickler for perfection. Even a menial job, such as sweeping the floor, had to be done thoroughly before it would pass his inspection.

Although their father demanded certain standards of work and behaviour, the Mitchell family enjoyed a happy and secure childhood. Being close to each other in age, there was always someone to play with, and they had the care and devotion of both parents. As so often happens, Mrs Mitchell had a soft spot in her heart for Billy, the youngest. She was a very beautiful woman, adored by all her children, but she also had a very determined streak in her character, a quality inherited by her eldest son.

At the age of eight, Reg Mitchell went to the Queensberry Road Higher Elementary School in Normacot. He had a lively, quick brain, and from an early age he was good at mathematics. His class teacher in this subject was Mr Jolly, a close family friend who lived just across the road from Victoria Cottage. Reg was also inventive and artistic, two gifts which were to play an important part in his career.

A few years ago, Gordon Mitchell received a letter from an ex-pupil at the Queensberry Road School, Beatrice Goulding, saying that she was in the same class as Reg.

Reg was always a very clever boy but we did not realise we had a genius in our class. As we read later about his wonderful achievements, we were so proud that we knew him. It seems dreadful that such a genius should die so young. A lot of us in the school with Reg were angry that more often than not little mention was made of the fact that he spent most of his young days in Normacot.

Beatrice Goulding sadly died in June 1985.

After finishing his elementary education, Reg moved on to the Hanley High School in Old Street, Hanley. Its use as a school ended in 1939 when it was commandeered by the Army. Subsidence damage subsequently condemned it as being unsafe for further use. It was while he was at this school that Reg first showed an interest in what was later to become his life’s work. In late 1908, ‘Colonel’ S.F. Cody became the first man to fly an aeroplane in England, achieving a flight in Farnborough of 496 yards at a height of up to 60 ft, and in the following year the Short brothers established an aircraft factory on the Isle of Sheppey. Reg was so excited by this new and wonderful idea of flying that he and his brother Eric began to make their own model aeroplanes.

The two Mitchell brothers had no kit or printed instructions to follow; they simply made up shapes of their own designs. As their pocket money was restricted to a few coppers a week, they could not afford to buy much. They used fine strips of bamboo cane to make the wings and fuselage and then glued on a layer of paper to ‘keep out the wind’. The parts of the model were held together by a covering of elastic material like stockinette. The propeller, carved out of wood, was turned by a twisted rubber loop. What fun they had as their fragile aircraft swooped and dipped over the lawns at Victoria Cottage.

As well as having a vivid imagination and an easy mastery of mathematics, Reg was also good at games. He was a sturdy, well-built lad, with broad shoulders and, as a capable batsman, he could always be relied upon to get the school cricket team out of trouble and this earned him a good deal of popularity.

At home in Victoria Cottage, there was never a dull moment when Reg was about. He was always inventing something new to amuse his brothers and sisters. He even made a small-sized billiards table, using stretched webbing fabric as cushions, and it gave the boys hours of entertainment. Reg played the game so often that his father, anxious for his son to do well at school, was heard to complain: ‘Reg will never pass his examinations if he spends so much time playing billiards.’ In spite of his father’s gloomy prophecy, he passed all his examinations, taking them in his stride as easily as he fashioned his model aeroplanes. His interest in flying increased when he started to keep racing pigeons and to send them over to France to compete in ‘homing’ races.

Though he sometimes seemed aloof and occupied with his own interests, Reg was always the leader and instigator of every youthful escapade. He was fond of his brothers and sisters, and his affection for his mother made him feel especially protective towards her favourite, young Billy. This was shown in an incident which occurred when Reg was twelve and Billy only a little lad. One evening, when Billy had been put to bed, the rest of the family sat in the room below enjoying a game of cards. Suddenly they heard a terrific bang overhead, followed by Billy’s frightened screams. Reg leapt to his feet and was upstairs in a flash, urged to greater speed by the sight of smoke coming out from under the bedroom door. Without a second’s hesitation he plunged into the smoke-filled room and, gathering up the sobbing little boy in his arms, he carried him out to safety. The gaslight was always left on until Billy was asleep, and on this particular evening a sudden gust of wind from the open window had flung the curtains against the gas mantle and they had immediately gone up in flames. The flames spread to a picture cord, and it had been the banging of the picture as it crashed to the floor which had alerted the family. Reg’s quick reaction probably saved his young brother’s life.

Reg enjoyed his school days, and in his spare time he devoured every scrap of information he could about aeroplanes. In the days when Reg was at school, flying as a mode of travel was only in the experimental stage, and the appearance of any aircraft was likely to make headline news. Reg was not a particularly studious lad – it would seem that he did not have to be from his exam record – he preferred making things to reading books, particularly fiction. He was very persistent. If he set himself a task he would finish it, no matter how boring and tiresome it turned out to be. Once, while still at school, he decided to read the entire works of Sir Walter Scott, though why he chose that particular author, no one knew. Hour after hour he sat on a stool by the kitchen range, ploughing through Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, Rob Roy and the rest, until his self-imposed task was completed. Anyone who has struggled through the duller pages of Scott’s narrative will have some idea how it must have been for a young and very active lad. But this gift of perseverance, of never giving up a task once he had started it, was one of the reasons for his future success as an aircraft designer.

In 1911, at the age of sixteen, Reg left Hanley High School and his father entered him as an apprentice at the locomotive engineering firm of Kerr, Stuart & Co. The works, situated in Fenton in the centre of Stoke-on-Trent, stood between the railway line and the river, and the firm provided a sound basic training in engineering. Reg, however, found this new life not entirely to his liking. All apprentices had to start work in the engine sheds, and this meant that he had to get up very early and travel down to Stoke on the workmen’s tramcar. It wasn’t the early rising that he objected to, but the fact that he had to wear overalls and carry his own lunch, which included the detested tea-can – a white enamel can with a handle and a lid serving as a cup – the sort of thing carried by all workmen at that time. Reg had just left school, where he had been a popular member of the first eleven cricket team, and he simply did not enjoy having to travel into town dressed in his overalls with his tea-can. At night he had to return home with grimy hands and with his overalls plastered with oil and dirt. He began to rebel against this daily ordeal, and when he could stand it no longer he openly protested to his father. But Mitchell senior, who was determined that his son’s training should be practical as well as theoretical, gave him a brief but emphatic reply: ‘You will go, my lad, and you will like it!’

One of his first jobs at Kerr Stuart’s was to make the mid-morning tea for his group of fellow-apprentices and for his foreman. It would seem that Reg and the foreman did not exactly hit it off right from the start. One day not long after he started his apprenticeship, having duly made the tea, Reg gave the foreman his mug, whereupon he took one mouthful and promptly spat it out saying, ‘It tastes like piss!’ Reg said nothing, but thought that if that was what he wanted, he would damn well get it. So next day he went off to the wash-room as usual to fill the kettle with water, but this time instead of tap water, he peed into the kettle. Having boiled it he made the tea and handed the mugs round having first warned his fellow apprentices not to drink any. The foreman took one sip, then another larger one and said, ‘Bloody good mug of tea, Mitchell, why can’t you make it like this every day?’ Honours about even on that episode, it would seem!

When Reg completed his training in the workshops, he moved on to the drawing office. Things now became much better as the hated blue overalls were a thing of the past. During his five-year apprenticeship at Kerr Stuart he attended night school, taking classes in engineering drawing, higher mathematics and mechanics, since he had already decided to make a career in basic engineering. He did so well in mathematics that, while he was attending the Wedgewood Burslem Technical School, he was awarded a special prize, one of three presented by the Midland Counties Union. Also, in 1913, he was awarded the second prize by the Union of Educational Institutions for his success in their examination in Practical Mathematics in the Advanced Stage. For his prize, R.J. selected Applied Mechanics by D.A. Low (1910), a textbook for engineering students.

While he was working at Kerr Stuart, Reg made a lathe which he was allowed to erect in one of the downstairs rooms at Victoria Cottage. Because he was so fond of making things, the lathe was in constant use, and it was Eric’s job to work the treadle with his foot. If he forgot what he was doing and let his foot slow down, he was quickly roused into vigorous action by a storm of protest from Reg.

His father, Herbert, was a very keen chess player and in due course introduced it to Reg, who found it interesting and soon became quite good at it, so that he quite often had a game with his father. The trouble, however, was that Herbert studied each move very carefully and hence took a long time before deciding what his next move should be. In marked contrast, Reg could usually decide on his next move (and that of his father) quite quickly. Understandably, Reg became more and more frustrated by what he considered to be the unnecessarily slow way in which his father played, while at the same time feeling that it would only upset him if he said anything about it!

As his work at Kerr Stuart progressed, Reg constructed a dynamo, making nearly all the parts himself, either at work or on his home-made lathe. A dynamo is not exactly a simple piece of apparatus, and the fact that he could make one entirely by himself showed his early abilities as a designer and engineer. Undoubtedly, these special gifts helped to bring him success later in his life.

Not content with his dynamo, Reg wanted to set up an electric light circuit. Victoria Cottage, like most houses at that time, was lit by gas and Reg was fond of reading in bed. He resented having to drag himself out from under the blankets to put out the gaslight hanging from a central point in the ceiling. To solve the problem he used a simple Leclanche cell battery and connected up the wires via a switch to an electric bulb hanging at the head of the bed. After that it was quite easy to put out the light when he had finished his book.

In all the various things he made, Reg showed an outstanding creative ability. He had tremendous energy and enjoyed hard work. Whatever he was doing, whether working or playing, he did it wholeheartedly. His gift for making things was encouraged by his father, who wanted all his children to develop their own interests.

In 1916, Reg left Kerr Stuart and began to look round for work. He was now twenty-one, and the First World War was in its second year. He made two attempts to join the forces, but each time he was told that his engineering skills would be of more use in civilian life. While he was looking for a job he did some part-time teaching in Fenton Technical School. In 1917, he applied for a job as personal assistant to Hubert Scott-Paine, the owner, at the Supermarine Aviation Works, Woolston, Southampton. One morning soon afterwards he rushed in to see his former teacher, Mr Jolly, waving a letter in his hand.

‘Just look at this!’ he cried. ‘It’s a letter from Supermarines inviting me to go for an interview.’

After a lengthy discussion, Mr Jolly and Reg’s father both agreed that it was a splendid opportunity. Reg was torn in two. He was attracted to the idea of working in an aircraft factory, but was reluctant to move so far from home, particularly because he was then courting Miss Florence Dayson, headmistress of Dresden Infants’ School. In the end he was persuaded to go. A few days later he travelled down to Southampton and so began a lifelong association with Supermarine.

2

Supermarine

All of Mitchell’s work as an aircraft designer was done at the Supermarine factory in Woolston, Southampton. This factory was started in 1912 by a remarkable man named Noel Pemberton-Billing. As a young man he had led an adventurous life in South Africa, and when he returned to England he was caught up in the new craze for ‘flying machines’.

While living on a boat, moored on the River Itchen in Southampton, Pemberton-Billing decided to set up his own aircraft factory. Looking round for a possible site he chose a disused coal wharf at Woolston. This piece of wasteland lay on the east bank of the river, just above the old Floating Bridge which for many years ferried people across the Itchen. As J.D. Scott states in his book, Vickers: A History, published in 1962 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson, who have given their permission to quote from it, Pemberton-Billing coined the name ‘Supermarine’, being the logical opposite of ‘submarine’, since he intended to specialise in machines which would fly over the sea.

The construction work at Woolston attracted the attention of the press. In November 1913 an article appeared in the Southampton Times and Hampshire Express under the heading:

Flying Factory at Itchen Ferry

Workmen are engaged on a stretch of river frontage between the Floating Bridge Hard and the old ferry yard, preparing premises for the construction of Supermarine...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Author

- List of Appendices

- Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Reference Sources

- Appreciation

- The Author

- 1 R.J. Mitchell

- 2 Supermarine

- 3 The Schneider Trophy

- 4 The Americans at Cowes

- 5 A Royal Visit to Supermarine

- 6 The S.4

- 7 The Southampton Flying Boat

- 8 The S.5: A Triumph for Mitchell

- 9 Welcome Home

- 10 The S.6: Victory at Cowes

- 11 1931: Britain Wins the Schneider Trophy Outright

- 12 The Last of Mitchell’s Flying Boats and Amphibians

- 13 The Spitfire

- 14 Mitchell’s Death

- 15 The Spitfire Goes to War

- 16 Development of the Spitfire

- 17 Production of the Spitfire 1940–45

- 18 My Father as I Remember Him

- 19 Memorials, Tributes and Events Associated with R.J. Mitchell

- 20 The Role of the Spitfire in the Battle of Britain

- Appendices

- Notes

- Illustrations