- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Prisons and Prisoners in Victorian Britain

About this book

Prisons and Prisoners In Victorian Britain provides an illustrated insight into the Victorian prison system and the experiences of those within it - on both sides of the bars. Featuring stories of crime and misdeeds, this fascinating book includes chapters on a typical day inside a Victorian prison - food, divine service, exercise and medical provision; the punishments inflicted on convicts - such as hard labour, flogging, the treadwheel and shot drill; and an overview of the ultimate penalty paid by prisoners - execution. Richly illustrated with a series of photographs, engravings, documents and letters, this volume is sure to appeal to all those interested in crime and social history in Victorian Britain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prisons and Prisoners in Victorian Britain by Neil R Storey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SOME INFAMOUS PRISONERS

The more infamous the case the more intense the clamour to learn about the behaviour of the accused while in prison and, if found guilty of a capital crime, their last hours in the condemned cell and their final moments on the gallows. When Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, the infamous eighteenth-century gaol breaker ‘Slippery Jack’ Sheppard and thief taker Jonathan Wild were still the subjects of broadsheets, books and melodramas, while infamous crimes such as the Ratcliff Highway murders (1811) and the Red Barn Murder (otherwise known as the Polstead Slaying), committed by William Corder upon Maria Marten in 1827, sold over a million broadsheets. And then there was James Greenacre, who murdered and dismembered his fiancée Hannah Brown, dumping her torso on the Edgware Road (1836). Their names were renewed to successive generations of children with threats like – don’t do that or Greenacre will get you! There were to be many more bogeymen and women before the end of the reign of Queen Victoria.

James Blomfield Rush (1848)

The first crime to really capture the public’s imagination during Victoria’s reign were the killings that became known as the Stanfield Hall Murders, committed by James Blomfield Rush at Stanfield Hall in Norfolk in 1848. In fact it was to become one of the most infamous crimes of the nineteenth century and contained all the potent factors to provoke Victorian attitudes of shock, horror and outrage. Books and broadsheets recounting every dramatic and lurid detail of the murder sold in unprecedented numbers; the broadsheet account of ‘Sorrowful Lamentations’ of the murderer sold an incredible two and a half million copies across the country. Columns, pages and whole supplements were given over to it in both local and national papers. Queen Victoria was recorded as taking a personal interest and even one of the greatest authors of his day, Charles Dickens, visited the scene and recorded his impression that it had ‘a murderous look that seemed to invite such a crime’. Simply the name of the location would stimulate talk of the crime and the dastardly deeds connected with it – Stanfield Hall.

James Blomfield Rush, the perpetrator of the murders, fitted the bill of a classic Victorian villain, not only in physical appearance in both build and dress but in his behaviour, manners, morals and sinister schemes that were exposed at his trial. His wax image ‘taken from life at Norwich’ was undoubtedly the star attraction in Madame Tussauds’ Chamber of Horrors in the last year of her life. Visitors were recorded as looking into his cold, glassy eyes ‘with the most painful interest’. The notoriety of James Blomfield Rush ensured his figure was on display in the Chamber for over 120 years.

Rush was not born into a family with a criminal background, but he was born to Mary Blomfield out of wedlock, in a time when scorn was poured on illegitimacy. James was baptised in Tacolneston Church on 10 January 1800. His father, William Howe, was successfully sued for breach of promise and Mary was awarded enough damages to provide the foundation of a good dowry when she married Old Buckenham farmer John Rush in 1802. John seemed to have taken to young James; he allowed him to assume the name of Rush and paid for him to receive a good education at the grammar school of Mr Nunn at Eye in Suffolk.

In the publications, written with hindsight after his execution, Rush was condemned as ‘always a bad one’, a debauched deceiver and swindler, some even went so far as to record that they ‘had always said Rush will be hanged’. The problem was that Rush was always trying to find legal loopholes and wrangles to get himself out of debt or bad financial commitments, he also failed to defend suits brought against him for seduction and bastardy by more than one complainant. Rush was to meet his match in a far better educated and higher-status man named Isaac Jermy, the Recorder of Norwich. However, Jermy was not a well-liked man. Many felt Jermy had obtained his home of Stanfield Hall by legal wrangle to the cost of the less well educated branch of his family, who were, in fact, the rightful heirs. Jermy was a man who knew the law and finance and was not afraid to use it to his advantage. As a short aside, both Rush’s wife and father had died in what could be construed, certainly in the light of later events, as ‘suspicious circumstances’.

W. Teignmouth Shore, the editor of ‘Trial of J. Blomfield Rush’ in the classic Notable British Trials series, eloquently sums up the dire situation Rush was in by November 1848:

(a) Pecuniarily Rush was in extremis

(b) Rush would shortly have to pay his landlord (Isaac Jermy) the mortgage on Potash Farm etc., a sum which he could not possibly raise

(c) He possessed documents from Thomas Jermy and John Larner, which if they should succeed in their claim to the Stanfield Hall and Felmingham estates would establish him again in security

(d) He hated Isaac Jermy

(e) Also, he held the forged agreements between Isaac Jermy and himself, which would be valueless unless the former died within a few days

To be precise, the loan on Potash Farm was due for settlement on 30 November 1848. On the night of Tuesday, 28 November 1848, a telegraph was received by the Norwich City Police stating that Mr Isaac Jermy and his son had been murdered. Upon their arrival at Stanfield Hall the scene was one of ‘utter dismay’ and the story of the night’s events soon unfurled. Between 8.15 p.m. and 8.30 p.m. Isaac Jermy Jermy (29), Sophie, his wife and one of Recorder Jermy’s daughters, Isabella (aged about 14), were in the drawing room about to sit down for a game of piquet. Recorder Jermy had, as was his habit after dinner, gone from the dining room to the entrance porch in front of the Hall to take in the evening air. A gunshot was heard and the butler, James Watson, came out of his pantry to investigate. Just as he reached the turn of the passage, to his horror, he was confronted by the figure of ‘a man in a dark cloak, of lowish stature, and stout, apparently with a mask on his face and something on his head’. The figure pushed the slightly built butler to one side, as he did so the butler noticed what be believed to be ‘two pistols, one in each hand’. Fearing for his life, Watson cowered at his pantry door as the figure strode on.

Jermy had also heard the shots and had run out of the drawing room and, across the staircase hall, to the door of the passage. Watson saw the cloaked man draw back a pace, level his gun at young Mr Jermy and shoot him at about 3ft distance through the right breast, causing his body to fall backwards onto the mat of the staircase hall. The assassin then crossed this hall toward the dining room. Upon hearing the second shot Mrs Jermy rushed out of the drawing room. She was horrified to see her husband lying on his back in a spreading pool of blood. She ran into the small square passage calling for Watson the butler and other servants where she met the housemaid, Eliza Chastney, who had heard the shots and ran to the calls of her mistress. The killer saw them and fired two shots in quick succession, the first catching Mrs Jermy’s upper arm, the second wounding Eliza Chastney in the groin and thigh. The murderer then made his exit by the side door. After medical examination it was thought Eliza had received ‘a whole charge’ that causes a compound fracture of the bone. The wound to Mrs Jermy’s arm eventually resulted in amputation.

Eliza testified: ‘I saw the head and shoulders of the man who shot me. There was something remarkable in the head; it was flat on the top – the hair set out bushy – and he was wide shouldered. I formed a belief at the time who the man was, I have no doubt in my own mind about it.’ She identified the man as James Blomfield Rush. She qualified her belief: ‘Mr Rush has a way of carrying his head which can’t be mistaken. No person ever came to Stanfield with such an appearance, beside himself.’

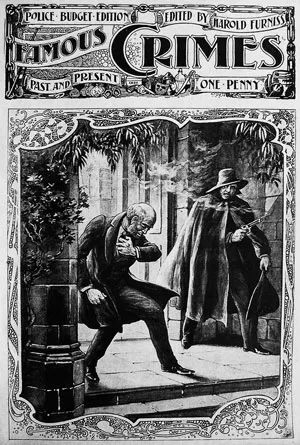

The Famous Crimes cover picture of the shooting of Isaac Jermy, the Recorder of Norwich at Stanfield Hall, by the heavily disguised James Blomfield Rush.

Rush was arrested at Potash Farm and removed to the nearby Wymondham Bridewell. On Thursday 30 November summonses were issued for a jury to hold an inquest at the King’s Head, Wymondham. The jury returned a verdict of ‘wilful murder’ against James Blomfield Rush and the coroner issued his warrant accordingly. After the magistrates’ hearing on 14 December 1848, Rush was committed to trial and he was removed to await his appearance at the assizes in Norwich Castle Gaol.

The trial opened on 29 March 1849 before Baron Rolfe. Rush had arrogantly turned down offers of legal counsel and opted to defend himself. He was often belligerent and attempted to intimidate the prosecution witnesses. The press and broadsheet sellers were having a field day, with extended accounts and illustrated supplements. The large crowds who gathered in front of the Shire Hall confirmed the vast public interest in the case. The drama was heightened still by the arrival of the injured housemaid, Eliza Chastney, who was carried to court upon a palanquin by police officers to give her evidence. From her canopied bed this brave young lady repeated her account of the night and confidently identified Rush as the murderer. Eliza’s evidence and her identification of Rush by his build, gait and shape of head were corroborated by Watson, the butler, and Martha Read, the cook.

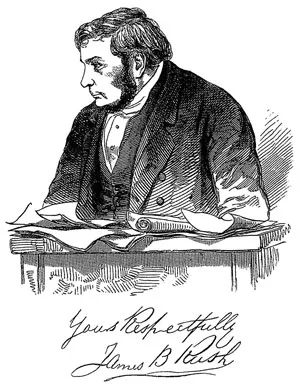

James Blomfield Rush, drawn from life in the dock, 1848.

On the fifth day of the trial, Rush, looking every bit the melodrama villain – bulky, aggressive and conceited, and dressed all in black – lumbered over from the dock to the witness box to deliver his defence. He was to speak, in total, for a marathon fourteen hours. More blustering, aggressiveness, fabrications, half-truths and barefaced lies typified his address, with sanctimonious intercessions opening with such proclamations as ‘God Almighty will protect me’ and ‘God Almighty knows I am innocent’. His five witnesses were hardly worthwhile, even damning; notable amongst them was Maria Blanchflower, a nurse at Stanfield Hall. She stated that she had seen the disguised murderer but did not recognise the figure as Rush, despite having run past within a few feet of him. Rush asked, ‘Did you pass me quickly?’ perhaps an unfortunate slip of the tongue, especially in open court!

After six days there had been a vast amount of evidence to digest, Rush had not helped himself with his convoluted and often irrelevant cross-examinations, but with the weight of evidence pressed against him he stood little chance of acquittal. The jury returned their verdict after just ten minutes deliberation – ‘Guilty’. Rush burst out: ‘My lord, I am innocent of that, thank God Almighty.’ When asked why the death sentence should not be pronounced upon him, the prisoner remained silent.

Baron Rolfe assumed the black cap and pulled no punches in a tirade against Rush. His vitriol is well evinced by his remarks; ‘There is no one that has witnessed your conduct during the trial, and heard the evidence disclosed against you, that will not feel with me when I tell you that you must quit this world by an ignominious death, an object of unmitigating abhorrence to everyone.’ During this final pronouncement Rush only spoke once, when the judge chided him for not making good his promise to Miss Sandford that she may well have invoked her legal right to refuse to testify against her husband. Rush, petty to the bitter end, replied, ‘I did not make any promise.’ Rush said no more, the sentence of death was passed, and he apparently regained his composure and was removed from the dock ‘with a smile and an unfeeling observation’ to the condemned cell of Norwich Castle Gaol to await his fate.

The behaviour of Rush in Norwich Gaol was very much the same as it was during the trial. He adopted the airs and phraseology of piety apparent in a devoutly religious man, but in Rush’s case, without the dignity. His act fooled no one. The clergymen who attended him listened to Rush in his hours of need and ‘sincere’ protestations of innocence but after Rush’s execution a sketch of Rush’s demeanour and conduct was provided by the prison chaplain, the Revd James Brown, Hon. Canon to the Cathedral and Minister of St Andrews. His opening comments sum up his opinion: ‘Rush, from the first moment of his apprehension, undertook a character which he was totally unable to support. He assumed the lofty and confident bearing of innocence; but he so unnaturally overacted his part, as to enable the most casual observer to see through the flimsy veil which he attempted to throw over his real feelings.’ Assiduously attending every religious service, reading the Bible and demanded regular attendance by the prison chaplain, Rush requested Holy Sacrament to be administered to him in private, but as Rush refused to be penitent or offer a confession for his crime, this latter request was refused. Displeased with the prison chaplain, Rush requested attendance from two other ministers known to him, namely the Revd W.W. Andrews and the Revd C.J. Blake. Rush also became increasingly belligerent towards these men as they could not promise to intercede on his behalf.

Rush had ensured he ate well in prison: refusing the prison food, he ordered his meals in from a nearby inn. In a letter dated 24 March 1849 to Mr Leggatt of the Bell Inn, Rush laid out his requirements:

Sir,-

You will oblige me by sending my breakfast this morning, and my dinner about the time your family have theirs, and send anything you like except beef; and I shall like cold meat as well as hot, and meal bread, and tea in a pint mug, if with a cover on the better. I will trouble you to provide for me now, if you please, till after my trial, and if you could get a small sucking pig in the market to-day, and roast it for me on the Monday, I should like that cold as well as hot after Monday, and it would always be in readiness for me … Have the pig cooked the same as you usually have, and send plenty of plum sauce with it. Mr Pinson will pay you for what I have of you. By complying with the above,

You will very much oblige,

Your humble and obedient servant, James B. Rush

The execution of James Rush was set for noon on Saturday, 21 April 1849. Rush prepared himself on the morning he was going to meet his doom with the breakfast of ‘a little thin gruel’ that he had requested, followed by a visit to the prison chapel. The service finished at 11.40 a.m., leaving the prison chaplain and Revd Andrews with Rush. They urged Rush to repent, but he only became irritated and said, ‘God knows my heart; He is my judge, and you have prejudged me … the real criminal will be known in two years.’ Rush then began to lose his temper, and, upon hearing Rush’s raised voi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction

- The Victorian Prison

- Prison Staff

- Admitting the Prisoner

- Daily Routine

- The County Prison

- The Convict Prison

- Punishments

- Escapers

- Rogues Gallery

- Some Infamous Prisoners

- Execution

- Select Bibliography

- Copyright