- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Royal Flying Corps Handbook 1914-18

About this book

Explores the contributions made by the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service during World War I. This work also covers aircraft, an array of other subjects including organization, pay, rank, uniforms, motor vehicles, the womens branches, attitudes, and even songs popular in the mess.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Royal Flying Corps Handbook 1914-18 by Peter G. Cooksley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE FOUNDATIONS

ARE LAID

The existence of the Royal Flying Corps was brief, less than six years to be exact, but during the period when it flourished it fought in the greatest war mankind had ever experienced, and it proved to be the precursor of what is arguably the finest and most efficient independent air arm in the world. This in turn became the pattern for the air forces of every nation that has emerged since. However, the birth-pangs of the Royal Flying Corps were protracted and painful. Only a year before it was formed, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir William Gustavus Nicholson, whose experience of warfare extended back to the Afghan War of 1878, had declared: ‘Aviation is a useless and expensive fad advocated by a few individuals whose ideas are unworthy of attention,’ although Orville Wright believed that he and his brother were ‘introducing into the world an invention which would make further wars practically impossible’.

It is not too fanciful to trace the beginnings of the RFC back to 1862 when Lieutenant Edward Grover RE began trials to investigate the military potential of balloons, basing his tests on a paper written by Captain T.H. Cooper of the 56th Regiment of Foot in 1809. However, it was not until 1878 that the War Office introduced the British Army to military aviation with the establishment at Woolwich of the so-called Balloon Equipment Store, at the same time allocating the sum of £150 for maintenance and equipment. Captains H.P. Lee RE and J.L.B. Templar of the Middlesex Militia (and subsequently KRRC), assisted by Sergeant-Major Greener, were appointed to oversee development work. Templar was a burly, genial man who was already an experienced aeronaut and owner of the coal-gas balloon Crusader, the first such vessel to be used by the Army. In the same year Crusader was joined by the 10,000cu.ft hydrogen Pioneer, specially constructed from varnished cambric at a cost of £71 – almost half of the original budget – before making its first ascent on 23 August 1878.

This sudden interest in lighter-than-air vehicles was in part due to the influence of Captain F. Beaumont RE and Lieutenant G.E. Grover RE, both of the Ordnance Select Committee. They had been attached to the Federal Army Balloon Corps during the American Civil War and subsequently made experimental ascents from Aldershot and Woolwich with equipment borrowed from the dentist and balloon pioneer Henry Coxwell.

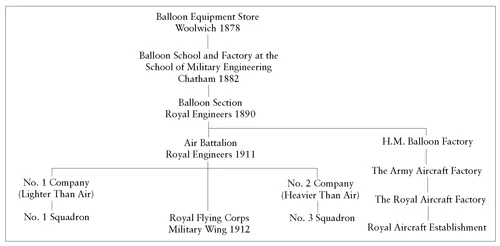

The emergence of the Royal Flying Corps. (Author)

In 1879 Crusader appeared at Dover during the Easter Volunteer Review and at Brighton twelve months later, when a programme of balloon training was begun at Aldershot. In the same year there was a balloon detachment at the summer Army manoeuvres. A year later, on 24 June, the Army manoeuvres saw the first use of a man-carrying balloon, and in October the complete unit, now termed the School of Ballooning, was moved to Chatham, becoming part of the School of Military Engineering. Captain Templar took charge of a small balloon factory in old huts belonging to St Mary’s Barracks. A derelict ball-court was reroofed and used as an erecting shop and old beer barrels held the granulated zinc and sulphuric acid necessary for the production of hydrogen. Rough and ready measures were adopted to save expense and later investigations resulted in the varnished cambric envelopes being replaced with those made of ‘goldbeater’s skin’ (taken from the lower intestine of an ox), which proved lighter, more impervious and stronger, and was used for the new 10,000cu.ft Heron, completed at the end of 1883. During this year, Templar was joined by Lieutenant John Capper RE, then serving with the 11th Field Company at Chatham, and in the search for new coverings the pair set about the construction of the experimental silk-covered and linseed oil-treated 5,600cu.ft Sapper in the search for new coverings.

With plans for Bechuanaland to become a British protectorate in 1885, the Army dispatched an expeditionary force which arrived in Cape Town on 19 December 1884. This force included an aerial section equipped with three balloons under the command of Captain H. Elsdale, assisted by Lieutenant Trollope, and although their use was confined to limited observation duties, it is interesting to note that the force commander, General Sir Charles Warren, made a number of ascents in the balloon Heron. In addition to the balloons themselves, the section would have needed to take all the necessary equipment, consisting of a horse-drawn, limbered winch-wagon, a single GS wagon and three tube-carts each carrying forty-four heavy steel gas cylinders. Each cylinder was 8in long and 51/8in diameter and contained hydrogen gas stored at 1,500lb/psi pressure in peacetime but increased to 1,800lb/psi on active service. The following year, on 15 February, another balloon section was posted overseas, this time to the eastern Sudan. It was commanded by (now) Major Templar, assisted by Lieutenant Mackenzie who achieved something of a record by remaining aloft for seven hours at an altitude of 750ft, while the balloon was towed along by the mobile winch in the centre of a marching column en route from Suakin to Torfrik. As a result of such operations, it was concluded that such lighter-than-air craft were reasonably successful as observation posts, although their full potential had not been realised owing to inadequate transport facilities. In 1888 Captain Elsdale, now returned to England, was succeeded by a friend of Major Templar, Major C.M. Watson, who promptly took steps to create a self-contained Balloon Section, requesting (unsuccessfully) that it should have its own horses and drivers since borrowing these from other units had been a frequent source of irritation. But within a few years this was achieved, reflecting the official realisation that there was a future for the new arm of the Army, although this was not supported by the niggardly grant for 1888 of £1,600, a reduction of £400 on that allocated two years earlier. Nevertheless it was not altogether surprising that the year 1889 was marked by the announcement that a detachment from the Balloon Section, acknowledged as the most interesting and novel branch of the Army and staffed by enthusiasts, should visit Aldershot during that year’s manoeuvres. Coupled with a favourable report on balloons for military work from General Sir Evelyn Wood, the GOC Aldershot Division, who had gained a Victoria Cross during the Indian Mutiny, this ensured that the Balloon Section was established on a regular basis in the following year. It was decided to move the section and the gas-producing establishment to Aldershot in 1891, the workshops and shed being occupied in the following year. The gas plant was set up adjacent to the RE’s Stanhope Lines, near the Basingstoke Canal, and the name ‘Balloon Factory’ came into use locally after the founding of the necessary workshops at South Farnborough in 1894 (although the name was not officially adopted until three years later). Three officers and thirty-three other ranks made up Superintendent Templar’s staff, forming in effect the nucleus of the future RFC, and the Army store now contained a total of ‘32 fully equipped balloons ready at an hour’s notice to go on active service’.

A British war balloon with its attendant horse team. (Author’s collection [380/16])

When the ‘Great Boer War’ broke out in October 1899, the Army still had only a single balloon section and depot stationed at Aldershot, but nevertheless a detachment of the Royal Engineers, including an aerial section, was among the British troops sent to Africa. This section, commanded by Captain Jones, made aerial observations before the Battle of Magersfontein in December, and the subsequent heavy losses among the troops on the ground could probably have been avoided if Lieutenant-General Lord Methuen had made proper use of the balloon observer’s report (although it probably saved lives later in the battle). However, there was partial redress for this blunder when information gathered by a captive Army balloon was intelligently used during the siege of Ladysmith between November 1899 and February 1900. This balloon was also used to survey the terrain across which troops were to advance on Pretoria in May and to provide reconnaissance information for the town’s subsequent capture by Lord Roberts’ troops in June. As a result of these operations, the strength of the balloon detachment was increased to twenty-one NCOs and men. By this time supporting equipment had improved and the gas wagons, increased in number to six, now carried thirty-five 9ft long, 8in diameter spun steel tubes each, enabling a balloon to be filled in twenty minutes.

As the new century dawned, technical innovations were introduced, some of which were later to be adopted for the Flying Corps. One of the most important was the transmission and receipt of wireless messages to balloons in flight, first achieved successfully in May 1904. Handling and controlling unpowered lighter-than-air vessels soon became established procedures, knowledge of which was to prove valuable for the Caquottype balloons used during the First World War for observation, to support defensive balloon aprons and to act as aerial barrages flown from ships such as the sloop Penstemon in 1917.

Early ground-to-air wireless experiments being conducted by the Army at Aldershot at a distance of 30 miles. (Author’s collection [156/19])

MAN-LIFTING KITES

Intended for observation, these kites could be operated in wind speeds of up to 50mph (much too strong for balloons), and were adopted by the Army in 1906. The idea of such kites was traceable back to 1894 when a team of kites capable of lifting a man to an altitude of 100ft was devised by Major B.F.S. Baden-Powell of the Scots Guards, brother of the founder of the Boy Scout movement. However, it was the kite-teams devised by S.F. Cody that were used by the balloon companies. These were capable of lifting an observer to an altitude of 1,500ft (over 3,000ft on one occasion). They consisted of a pilot kite below which were three to seven lifting kites, according to the wind strength; suspended beneath the lifting kites was a carrier kite, below which was the observer’s basket. The first man to be lifted by this system was a sapper who went aloft over Pirbright Camp.

June 1894 saw the establishment of the Army’s Balloon School. S.F. Cody was appointed Chief Instructor, Kiting, and during 1906 secret investigations were launched to look into the possibilities of powered gliders. Lieutenant J.W. Dunne, who had been invalided out of the Army, was appointed designer of man-lifting kites at HM Balloon Factory, where he soon designed a tail-less glider, which was eventually powered by a pair of Buchet petrol motors. This proved capable of making short hops twelve months later.

But the advent of such devices did not mean that work on balloons had been abandoned. In 1903 and 1904 there were trials with a balloon flown from a destroyer taking place over Malta and Gibraltar. More reliable petrol motors were fitted to large balloons, creating a new form of transport – airships. Little more than an elongated, motorised balloon, Nulli Secundus – otherwise known as Army Airship no. 1 – was begun in 1904 by the Balloon Factory following Colonel Capper’s visit to the pioneer aviator Santos Dumont two years earlier. It was launched in September 1907 and in the following October it made its greatest – and last – flight. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Quote

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One The Foundations are Laid

- Chapter Two The Crucible of War

- Chapter Three Uniforms, Flying Clothes and Badges

- Chapter Four Lighter Than Air

- chapter five Airships: Shadows in the Clouds

- Chapter Six Fixed Wing Aircraft

- Chapter Seven Men and Machines

- Chapter Eight Significant Actions

- Chapter Nine The New Arm is Developed

- Chapter Ten Wars Unceasing

- Chapter Eleven The Women’s Services

- Afterword The Foundations are Built Upon

- Appendix I The Songs They Sang

- Appendix II Facts and Figures

- Valediction

- Bibliography

- Copyright