eBook - ePub

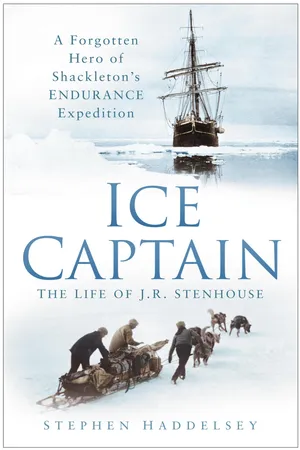

Ice Captain: The Life of J.R. Stenhouse

A Forgotten Hero of Shackleton's Endurance Expedition

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ice Captain: The Life of J.R. Stenhouse

A Forgotten Hero of Shackleton's Endurance Expedition

About this book

Much has been written on Antarctic explorer, Ernest Shackleton. This is the story of the Endurance expedition's other hero, Joseph Russell Stenhouse (1887-1941) who, as Captain of the SS Aurora, freed the ship from pack ice and rescued the survivors of the Ross Sea shore party, deeds for which he was awarded the Polar Medal and the OBE. He was also recruited for special operations in the Arctic during the First World War, became involved in the Allied intervention in Revolutionary Russia, and was later appointed to command Captain Scott's Discovery. Stenhouse was one of the last men to qualify as a sea captain during the age of sail.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ice Captain: The Life of J.R. Stenhouse by Stephen Haddelsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE APPRENTICE IN SAIL

On a late summer’s morning in 1904, two figures might have been seen making their way along the crowded quaysides of South Shields, on the north-eastern coast of England. Followed by a porter pushing a conspicuously new-looking trunk on a handcart, they had made their way from the railway station, negotiating the squalid streets of poor housing that tumbled down towards the docks and which, for all South Shields’ prosperity, were inhabited by wretched-looking children, filthy and shoeless. The shorter of the two pedestrians, middle-aged and well-built, strode with confidence among the cables, crates and assorted impedimenta of the busy port. He seemed impervious to the stench of the herring fisheries, wafted by an inshore breeze from North Shields, and cast quick, appraising glances at the vessels crowding the harbour. The other, for all his powerful, loose-limbed build and 6ft 1½in, looked altogether less self-assured, as might be expected of a boy only just approaching the threshold of manhood. Andrew Stenhouse, engineer for Vickers & Maxim, the great shipbuilder and armaments manufacturer, and his 16-year-old son, Joe, had just travelled by train from Barrow-in-Furness, the latter nervously clutching a letter he had received a fortnight before from the offices of the Andrew Weir Shipping & Trading Company. The crumpled paper advised him that ‘we have arranged for you to go in our Barque Springbank’ and that he should hold himself ‘in readiness to join her in the Tyne’.1

Only a few weeks earlier, Joseph Russell Stenhouse had been employed as a clerk in the Barrow offices of Lloyds Register of Shipping. Having left Barrow’s Higher Grade School,2 aged 14, for two years the muscular and square-jawed youth had perched upon a high stool in an airless room, slaving at his duties and proving himself, according to his employer’s glowing reference, ‘willing, obliging and attentive’. But he had found it impossible to settle for a life of pen-pushing drudgery and, with each passing month, what he would later call the ‘strange, strange call’ of the sea had sounded ever more resonantly in his ears. That he should be receptive to this siren call was not, perhaps, particularly surprising, as his family had a long established connection with the sea. His grandfather, also called Joseph, had started life, like his father before him, as a ship’s carpenter but, by 1875, his ability and drive had resulted in his taking over his employer’s shipbuilding yard, and in his founding the firm of Birrell, Stenhouse & Company at Woodyard, Dumbarton.

It was at Woodyard, on 15 November 1887, that the patriarch’s namesake had been born. And here also, on 17 May 1889, that he had watched the launching of the firm’s last great sailing ship, the Elginshire. A near-drowning, which left the child black in the face and full of foul water, failed to instil any fear and the constant proximity of sailing ships, both in Woodyard and in Barrow, where his family moved when he was 2 years old, left an indelible mark on the boy’s soul. The culmination of these influences had been a decision to abandon his desk at Lloyd’s and to sign on for a four-year apprenticeship with whichever shipping company would have him. Andrew Stenhouse attempted to dissuade his son from the daring step he now seemed determined to take, but his arguments rang rather hollow and, after dutiful consideration, they were ignored. It was, as Andrew himself must have been well aware, a predictable case of ‘like father, like son’. For he, too, had once fallen victim to the lure of the ocean, and had served as an apprentice at sea3 before becoming a manager with the family firm, a position he continued to hold until Birrell’s bankruptcy and the decline in demand for sailing vessels forced him to seek employment with Vickers.

Now, the Springbank lay before them and her 282ft length and 43ft beam would mark the boundaries of the young Stenhouse’s world for many long months to come. She was, as the newest member of her crew later admitted, distinctly unprepossessing in appearance: her iron hull streaked with rust and the water surrounding her made almost metallic by the pollution of fish scales and oil. Originally built for the nitrate trade and launched in Glasgow in September 1894, Springbank had spent the last decade ploughing the world’s oceans carrying cargoes consisting mostly of timber and coke. Four-masted and jubilee-rigged, she now sat low in the water, her Plimsoll line tickled by the unctuous swell.

Announcing their business, father and son received permission to come aboard and, followed by the shiny trunk, they crossed from shore to ship. A brief tour of inspection followed, during which Andrew Stenhouse cast an expert eye around his son’s new berth, taking in her bluff bows and her stump topgallant masts with their square rig, and the fine run aft which gave such promise of excellent sailing qualities. The unexpectedly pungent atmosphere of the claustrophobic afterdeck lavatory, however, brought the tour to a sudden halt – followed by a hasty disembarkation of the retching engineer. His son followed sheepishly, acutely aware of the impression that their rapid departure must have made on his shipmates-to-be. They exchanged farewells on shore; Andrew memorised a last message for Joe’s stepmother4 and 18-year-old sister, Nell, left in Barrow, and then the new apprentice returned to his ship. The Springbank’s cargo of coke and general goods had already been loaded and within a few short hours she put to sea, bound for San Francisco via the Cape Verde Islands and Cape Horn. The boy standing on her deck and the anxious parent watching her departure from the shore each knew that a year or more must pass before the Stenhouse family would be reunited.

Under grey skies, the Springbank slipped out of the Tyne and into the North Sea, round the coast of East Anglia and down into the English Channel, before pushing her nose out into the deep, open waters of the North Atlantic. Stenhouse had been given his first job within hours of boarding: being sent aloft to reef the jigger-masthead flag halliards, high above the deck. He later recorded that ‘although I had no fear, when I hauled myself clear of the futtock rigging and found no ratlines beyond the topmast rigging, I began to feel the strain.… Eventually, after a great effort, I reached the masthead pole, and with beating heart, and legs and arms clutching the mast and backstays, I rove the end of the halliards through the truck, overhauled them and started to come down.’5 He reached the safety of the deck totally exhausted, with his palms flayed by an unintentionally precipitate descent down the backstays but also with a chest expanded with a sense of achievement. His shipmates, however, quickly disabused him of any notion that the minor victories, the opinions or the comfort of a ‘first voyager’ carried any weight in the ship. Of the seven apprentices aboard, three, including Stenhouse, were complete novices and, as such, the more experienced hands considered them worse than useless. It must have been a galling realisation for a boy who had grown up with sailing ships, whose grandfather had built and launched many vessels such as the Springbank, and in whom family pride waxed strongly.

Mercifully, the routine of the ship allowed little time for introspection. The hours were long and the work arduous, particularly for one who, despite his stature and bodily strength, possessed little experience of such intense labour. Of course, the first voyagers were chosen for the least skilled and most tedious tasks. These included all the cleaning duties, from filling the captain’s bath to scrubbing the bilge; striking the bell with the regularity of clockwork; and hauling on a sheet or clewline whenever the demands of the moment required unskilled muscle to be applied.

Undertaking these and a hundred other tasks, inevitably Stenhouse found that he was thrown together a good deal with his fellow apprentices. These residents of the half deck proved to be a mixed bunch including three Englishmen, two Scots, one Australian and one Belgian, but they quickly bonded into a tight-knit group. They had little choice, as they found themselves the butt of every joke. Stenhouse proved no exception to the rule and, in his diary, he recorded one trick that a wiseacre among the crew attempted to play on him. ‘We are painting our house,’ he noted, ‘and are consequently sleeping on deck at night and I was awakened by my mattress being drawn from under me as I slept on the main (No. 3) hatch this morning. I didn’t know what was the matter at first, but when I saw my mattress going aloft at the end of a rope I made a dive for it and managed to get hold of it and cut it adrift in time to save it from being sent up to the main yard.’6 With the assumed wisdom and condescension of an old hand, he concluded his entry with the remark that ‘This is a common trick at sea and also is [sic] the tying of a man to the nearest fixture; Douglas, one of the Port watch being tied to the ring bolts, on the hatch casements.’7

Gradually Stenhouse came to know his other shipmates as well, though they seldom allowed him to forget his lowly position in the shipboard hierarchy. The able seamen generally treated the apprentices with a rough kindliness not far removed from contempt. Then came the three mates and, at the apex of the social pyramid, the dour, red-whiskered captain, who saved his smiles for his cabin and for the young wife and baby daughter who sailed with him. But Stenhouse seldom had anything to do with the captain who, so far as the apprentices were concerned, remained as aloof and remote as Ahab. Having agreed to take them, however, the ‘old man’ felt obliged to make some attempt to educate the boys as seamen and prospective officers and so, sometimes, Stenhouse and his companions would be made to stand on the poop staying the ropes and boxing the compass. But, for the most part, they remained in blissful ignorance as to the ship’s course and speed. When writing his diary, Stenhouse often left space to record latitude and longitude but he seldom obtained sufficient information to fill these gaps and the unspoken assumption was that he and his fellows would learn by hard labour, by emulation and by observation – or not at all.

Towards the end of October, the atmosphere on board changed as the crew became engaged in a variety of bizarre activities, apparently more akin to a child’s birthday party than to the backbreaking toil of a working merchant vessel. Mature and experienced seamen, usually taciturn and scruffy to the highest degree, now laughed like schoolboys as they dyed their old slops or laboured like fashionable Parisian hairdressers to create wigs and false beards. The cause of their hilarity and industry was the proximity of the Equator. Ancient tradition demanded that ‘crossing the line’ should be marked with an uproarious ceremonial during which those who had never before passed between the northern and southern hemispheres were subjected to a rough, if usually good-humoured, initiation. And they left Stenhouse and the other first voyagers in no doubt as to their role in the forthcoming proceedings. The older sailors winked at them and laughed among themselves, while the second voyagers taunted them with stories of rough handling, near-drowning and humiliation before the assembled crew.

The preparations, which provided a welcome break from the routine of shipboard life, continued for three weeks until, on the morning of 19 November, thirty-three days out from South Shields, the Springbank crossed the line. At 8.30 a.m., as Stenhouse swallowed his last mouthful of breakfast, a whistle sounded, ‘that being the Sergeant’s signal to his four policemen to come and lay hold on some first-voyager’. Stenhouse had already decided on his course of action:

As soon as I heard the whistle I put some biscuits in my pockets and made a dash for the poop, meaning to go down the sail locker and hide from the policemen, but I met the Mate and he sent me down on deck again. Running into the half-deck again I jumped into the clothes locker and one of the second-voyagers shut [the] door on me. After about a quarter of an hour one of the policemen came into the half-deck and searched everywhere, clothes locker as well, even putting his hand on my shoulder, but did not see me. After another short lapse of time another sergeant came, this time he got me and blowing a whistle in rushed four men in blue, armed with belaying pins, the sergeant himself having a wooden dagger, with which he probed me when I refused to come out of the locker. After about five minutes struggling, during which I got a few cuffs on the head and other parts with the pins, they got me out and carried me forrard, kicking all the while, and dumped me head first into the port WC …8

Half an hour later, as he waited to be dragged before his judge, another first voyager opened the door – and he made a second bid for freedom. This time the unwilling neophyte climbed up into the rigging. He smiled to himself at the surprise of his jailers when they found that ‘the bird had flown’, but his escape was only temporary. Soon his pursuers spotted him on the topgallant yard and, when he refused to descend, the Mate who throughout the proceedings had evidenced his firm belief in tradition, ordered him to return to the deck. Immediately his feet touched the planking, the policemen blindfolded him and then dragged him, still struggling, before Neptune who sat in state on a box covered with a Union Jack. Asked his age, Stenhouse forgot himself so far as to attempt a reply:

I opened my mouth to speak, when the Soap Boy, who was rigged with a fancy head piece of rope yarns and reddened on his face with red lead, shoved in some pills, which the Doctor had made of soap, etc. Then came the tarring, after being stripped to my waist, I was tarred with a brush and then scrubbed with a broom. This was repeated again and again and then I was shaved with a wooden razor, the blade of which was about two feet long. Then they dumped me in the bath and kept my head under long enough to make me think I was drowning.9

Still undaunted, as soon as he surfaced, Stenhouse grabbed a tar brush and tried to belabour one of the policemen, but his tormentors quickly overpowered him and made him submit to another shave, before finally handing him his hard-earned certificate for crossing the line.

Although he resisted such indignities with all his might, and received a sound cuffing in reply, Stenhouse’s strength and courage earned him the respect of many of his shipmates. Unfortunately, these qualities, his unwillingness to suffer in silence beneath a slight, whether real or perceived, and his refusal to ‘turn the other cheek’ also led him into direct conflict with his superiors. But, as he would later state, ‘a man without pride is no man at all’10 and, despite his avowed respect for authority, any offer of violence would be instantly and vigorously reciprocated. Still only 16 years old and on his first voyage, this bullish attitude resulted in a bout of fisticuffs with the belligerent second mate. One watch, this Irishman, ‘hefty as a bullock’ and impatient of any impertinence or slackness, took exception to the unusually musical manner in which the young apprentice struck six bells [at 11 p.m.]. When he asked Stenhouse to explain himself, he took further umbrage at what he took to be the boy’s insolent response and, rather than debate the issue further, he resorted to his fists. Fortunately for Stenhouse, his own length of reach made him a match for the mate’s greater bulk, and within seconds they were locked in a clinch which only the appearance of the enraged captain brought to a close. An act of insubordination which, on a ship of the Royal Navy would have ended in the direst consequences, resulted in nothing worse than the loss of an hour’s sleep in each watch below, during which Stenhouse paced the flying-bridge between the poop and the after deck-house, with a heavy capstan-bar balanced on each shoulder. Such lessons proved salutary and an unbending demand for discipline at sea, gradually and unconsciously imbibed, would become second nature. In later life, indeed, and in conditions of both war and peace, men under his command would learn that Stenhouse would have no truck with indiscipline, that he could be a martinet altogether more exacting even than the Springbank’s officers.

He learned other lessons as well: the most potent of all being love of the ocean and of the sailing ships that plied their trade across its ever-changing surface. Even before taking to the sea, Stenhouse possessed a strong feeling of family pride: pride in the three – now four – generations who had made the sea their trade; pride also in the vessels which his family had launched and which he occasionally recognised in the ports and harbours visited by the Springbank. Now he added to these feelings a deep and enduring love of the ships’ grace and beauty under sail, qualities made all the more poignant by his realisation that he was witnessing the nadir of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Author’s Note

- 1 The Apprentice in Sail

- 2 South with Shackleton

- 3 Arrivals and Departures

- 4 Adrift in McMurdo Sound

- 5 Prisoners of the Pack

- 6 Aurora Redux

- 7 The Mystery Ships

- 8 War in the Arctic

- 9 The Syren Flotilla

- 10 Discovery

- 11 Oceans Deep

- 12 The Final Season

- 13 Pieces of Eight

- 14 Treasure Island to the Cap Pilar

- 15 Thames Patrol

- 16 With His Boots On

- Notes and Sources

- Select Bibliography

- Copyright