![]()

1

HEIRS OF THE CID

When in ancient or modern times has so great an enterprise been undertaken by so few against so many odds, and to so varied a climate and seas, and at such great distances, to conquer the unknown?

Francisco López de Jerez

Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú

The history of Spain’s conquest of the Inca empire of Tahuantinsuyo is as much a history of the destruction of a civilization as it is of its protagonists and victims: conquistador and Indian alike, some of whose names are recorded by history, and others forgotten in the faded parchments of some distant archive. As with much of colonial history, it was a history of a conquered people written by its conquerors, and revised in part by the chronicles of later missionaries and Crown officials. Almost nothing in any great biographical detail is recorded of their lives. As illiterate as the people they had conquered, their silence was to prove their greatest defence of the wealth they accumulated, and of the inhumanity with which they had established their empire: a social and economic infrastructure which would still be evident in Andean America until the agrarian reforms of the present century.

That each of the conquistadors of the New World was tainted with the blood and brutality of their conquest is without dispute. Neither was their role any different from that of their forefathers who had fought in the reconquista of Muslim Spain and shared in the booty of its destruction, nor can their undoubted courage be denied them. Their story is not of a great religious crusade but of explorers and would-be mercenaries, whose treatment of the natives they subjugated was possibly no more bloody than the crusading armies which had ransacked their fellow Christians at Constantinople on the way to the Holy Land three hundred years previously, or in any of the later religious wars of Europe. With scant knowledge of handling the arms they purchased or borrowed, and united solely by their poverty and the dream of riches that had brought each of them to the Indies, they were to conquer one of the greatest empires of the Americas. Nor as colonists did they differ in their sense of racial superiority to any other latter day European colonist; nor was the plight of the people they conquered any less humane than that of an African, North American Indian or Aborigine. Neither was their racism dissimilar to that of any other European, nor even of the humanist Erasmus who chided the Spaniards for having too many Jews in their country.1

The legacy of their cruelty would transcend the centuries, inspired in part by the writings of the Dominican Bartolomé de las Casas, whose condemnation of the treatment of the natives of the New World would later be revived by Protestant pamphleteers in elaborating the leyenda negra, black legend, of Spain’s conquest. ‘There are many who were never witnesses to our deeds, who are now our chroniclers,’ the Conquistador Mansio Serra de Leguizamón complained in his old age, ‘each one recording his impressions, often in prejudice of the actions of those who had taken part in the Conquest . . . and when they are read by those of us who were the discoverers and conquistadors of these realms, of whom they write, it is at times impossible to believe that they are the same accounts and of the same personages they portend to portray.’2

The homelands and social hierarchies the conquistadors left behind in their poverty stricken villages of Castile, Estremadura and Andalusia had evolved in the feudalism of the Middle Ages: an era that had transformed Spain from an amalgamation of semi-autonomous Visigoth and Arab kingdoms into a nation of imperial power. It had also been an age that had seen the throne of Spain inherited by the Flemish-born grandson of Queen Isabella of Castile and her consort King Ferdinand of Aragón, who as Charles V would be elected Holy Roman Emperor and succeed to the great Burgundian inheritance of the Low Countries and to the kingdom of Naples: a legacy which would divide the political and religious map of Europe, and in time witness Spain’s hegemony of the New World.

The realm the young Austrian Prince Charles of Habsburg inherited from his Spanish mother and grandparents was a land steeped in the exorcism of its past Arab and Judaic civilization, the last symbolic vestige of which had been the surrender of the kingdom of Granada in 1492. This was the same year his grandmother’s Genoese Admiral Columbus had first set foot on the Caribbean island of Guanahaní he had believed to be the gateway to India, and for which reason the Americans would be known as Indians. In the eighth century possibly 1 million Arabs and North African Berbers had crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and had settled in the Iberian Peninsula, three-quarters of which by the eleventh century had been under Muslim rule,3 populated not only by Christians but by a large urban Jewish community. It was a land separated as much by its geographical contrasts as by its racial division.

Only in the mid-thirteenth century had Spain’s Christian armies re-established its former Visigoth capital, at Toledo. The reconquered territories were placed under the protection of encomiendas, lands entrusted by the Crown to families of old Christian lineage, Cristianos viejos, and held in lieu of feudal service. Evangelical as well as territorial in its purpose, it was a system that would dominate the social structure of a vanquished people, destroying both their identity and traditions. With similar effect it would be introduced by the conquistadors to the colonies of the New World, and which in all but name would become a licence for slavery. The fate of the country’s Jews had followed a similar course of persecution. The tax returns of Castile in the year 1492, whose kingdom comprised three-quarters of the Peninsula’s populace of an estimated 7 million people, record some 70,000 Jews, almost half of whom would refuse to accept conversion and face exile in Portugal4 or North Africa.5 Those who remained, known as conversos, as in previous centuries, would be assimilated into a society governed by the tenets of a religious Inquisition, in which they would face the stigma of their race in the proofs of limpieza de sangre, racial purity – an anachronism that would perpetuate unabated well into the nineteenth century.6 Even St Teresa of Avila, venerated by king and courtier alike, would never disclose the ignominy shown her grandfather, a converso, who had been publicly flogged in Toledo at an auto-da-fé for his apostasy.7

It was an image of a people in every level of their existence: of a predominant and mainly destitute peasant society governed by its Church and feudal nobility, which owned 95 per cent of the land;8 and of a small urban middle class, of tradesmen, artisans and clerks, many of them incorporated in the Hermandades, guilds, dependent on the Crown for their privileges. The hidalgo – hijo de algo, son of a man of rank – represented an untitled nobility which for generations had served the Crown as soldiers, or as warrior monks in the Military Orders modelled on the crusading Orders of the Holy Land. Bound by their distinct codes of chivalry, they had traditionally derived their livelihood from the booty of war and from the rents of their small country estates, regarding trade and any form of commerce as below their dignity; a stance that brought many of them to penury, and which Cervantes satirized in the characterization of the hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha. Some were landless and lived in townships or in the garrison castles of the Orders: Calatrava, founded in 1158 for the defence of Toledo by Ramón Sierra, Benedictine abbot of the Navarre monastery of Santa María de Fitero; Alcántara, founded in about 1170 for the defence of Estremadura; and Montesa, founded in 1317 by King James II of Aragón as the result of the disbandment of the Templar Order, whose lands he acquired.

The Order of Santiago, founded in about 1160, was however the most prominent of all the Orders, owning some quarter of a million acres of land. It was established by knights of León for the protection of pilgrims to the shrine of St James the Apostle, at Compostela in Galicia, where, according to tradition, his body was buried. Proclaimed patron of Spain and its armies because of his legendary apparition at the Battle of Clavijo in the ninth century, his image as Santiago mata moros, slayer of Moors, mounted on a white horse in full armour would emblazon its banners during its wars in Europe and in the conquest of both Mexico and Peru. St James’ emblem of the cockleshell owes its origin to the legend that at Clavijo a Christian knight discovered his chain mail studded with cockleshells after making his escape across the River Ebro: a symbol synonymous with pilgrimage to his shrine at Compostela. With the demise of Muslim Spain the Orders would witness the end of their crusading role, their lands and wealth prey to the political and financial demands of the Crown.9 It would also symbolize the end of the hidalgo as a crusader knight, relegating him to the romances of a bygone age, and his title to a mere appendage of nobility.

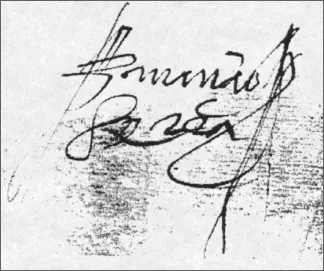

Mansio’s signature. (Patronato 126, AGI, Seville)

The conquistador Mansio Serra de Leguizamón was one of the few hidalgos to have taken part in the discovery and conquest of Peru,10 most of whose 330 known volunteers were from the humblest backgrounds, the sons of yeomen and tradesmen. He was born in the year 1512, three years before the birth of St Teresa of Avila, in the township of Pinto in the realm of Toledo, in an age that could still recall the reconquest of Granada and had witnessed the discovery of the New World. He was the son of Juan Serra de Leguizamón, a Vizcayan,11 and of María Jiménez, whose Castilian family had lived in the township for generations.12

Mansio’s father, who probably typified the plight of the impoverished hidalgo at the turn of the century, was descended from the families of Serra, of Ceánuri and of Leguizamón, of Echévarri near Bilbao, the arms of which the Conquistador bore, and whose faded carving can still be seen on the portico of his mansion in Cuzco. From time immemorial Iberia’s northern province on the shores of the Bay of Biscay, bordering the Basque lands and Pyrennean kingdom of Navarre, had possessed its own language and fueros, privileges, as subjects of its feudal lordship, which only in the fourteenth century had been assimilated into the Crown of Castile. The Victorian writer Richard Ford, who travelled widely across its mountainous land, referring to the language of its people, quotes a common saying that the Devil had studied Vizcayan for seven years and had accomplished only three words. ‘A people,’ he wrote, obsessed by their independence and lineage, ‘. . . whose armorial shields, as large as the pride of their owners, are sculptured over the portals of their houses, and contain more quarterings than there are chairs in the drawing rooms or eatables in the larder . . . and well did Don Quijote know how to annoy a Viscayan by telling him he was no gentleman’.13 According to the fifteenth-century Vizcayan chronicler and genealogist Lope García de Salazar,14 the Leguizamón were descended from Alvar Fáñez de Minaya, a cousin of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known to history and legend by his Moorish title of el Cid, the Lord: both of whose names would embellish the ballads of the Middle Ages and inspire the epic poem of that name.

Seigneurial families of Vizcaya at Guernica, El Besamanos, Francisco de Mendieta, 1609. (Diputación Foral de Vizcaia)

Of the lineage of Alvar Fáñez de Minaya, cousin of the Cid of Vivar, succeeded a knight who came to settle the lands known as Leguizamón, and there founded the House of Leguizamón the old many years before Bilbao was populated, and from father to son was succeeded by Diego Pérez de Leguizamón, a fine knight and held as the noblest of his name, who bore for arms horizontal bars as borne by the said Alvar Fáñez de Minaya in his sepulchre at San Pedro de Gumiel de Hizán where he is buried, and which this lineage bears, and who in turn was succeeded by Sancho Díaz de Leguizamón who was killed in the vega of Granada . . .15

What history records of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar is that he was born in the mid-eleventh century and that for several years he had served King Sancho of Castile as his constable until his murder at Zamora in 1072.16 Exiled from Castile by Sancho’s heir and brother Alfonso VI, for eighteen years he commanded the armies of the Emir al-Mu’tamin of Saragosa and his own Castilian and Moorish mercenaries, eventually capturing the Muslim city and kingdom of Valencia, where he died in 1099. His exploits and life were recorded in the twelfth-century poem chronicle Carmen Campi Doctoris, Song of the Campeador, and then later by a prose chronicle Historia Roderici, and in the epic medieval poem Mio Cid.17 Though Alvar Fáñez de Minaya is depicted in Mio Cid as his trusted commander, there is no evidence that he ever accompanied him in his exile as the poem purports. In the Poema de Almería, written in about 1152, Minaya is described as the most renowned of the Christian warrior knights, second only to the Cid: Mio Cidi primus fuit, Alvarus atque secundus.18 In 1091 he is recorded as commanding one of the armies of Alfonso VI against the Berber Almoravides which was defeated at Almodóvar del Rio. Six years later, Alfonso appointed him governor of the fortress of Zorita and then of Toledo, which he defended against the Berber siege. In 1114, while in the service of Alfonso’s sister, the ...