- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The landscape has had a huge impact on the history of Liverpool and Merseyside. The ice age glaciers carved out the Rivers Mersey and Dee; the Sefton coast provided a perfect place for the earliest humans to hunt and gather food; and the Pool and the Mersey, and England's position on the coast gave King John the perfect base from which to launch his Irish campaigns. This book explores the landscapes from these earliest times, and charts the changing city right through to the present day. It explains why Liverpool looks the way it does today, and how clues in the modern landscape reveal details of its long history. You'll see how the landscape created Liverpool, and how in turn Liverpool recreated the landscape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Liverpool: A Landscape History by Martin Greaney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

FROM THE EARLIEST PREHISTORY

TO THE FOUNDING OF LIVERPOOL

GEOLOGY AND THE LAST ICE AGE

Liverpool’s historic landscape is built upon the geology which underlies it. To understand the history of Liverpool is firstly to understand the rock it was built upon, and from. The very oldest rocks beneath the city are Carboniferous (360 to 300 million years old) which consist of limestone and sandstone, and contain coal. These were formed from the decayed plant material laid down in wide, swampy river deltas, as this area formed part of the coastline at the time.

On top of this sit Triassic rocks (250 to 200 million years old) which were formed at the edge of an arid, desert mountain range. The softer Triassic rocks (such as the characteristic red sandstone of which much of Liverpool’s older buildings are constructed) have been weathered into the Cheshire and Lancashire plains which sit to the north and south of Liverpool, while the harder Carboniferous rocks juts out to either side of the Triassic to form the Welsh uplands in the west and the foothills of the Pennines in the east.

As we’re interested in the geology which influenced later history, it’s worth pointing out that the geology provided many of the raw materials which went into building Liverpool or (via export) its wealth. Sand, clay, building stone, salt and underground water were all exploitable materials present in the ground across the region before Liverpool was founded. Coal could be found in great quantities in Wales and Lancashire to the east and west of Liverpool, but another, smaller, pocket was exposed in the grounds of Croxteth Hall.

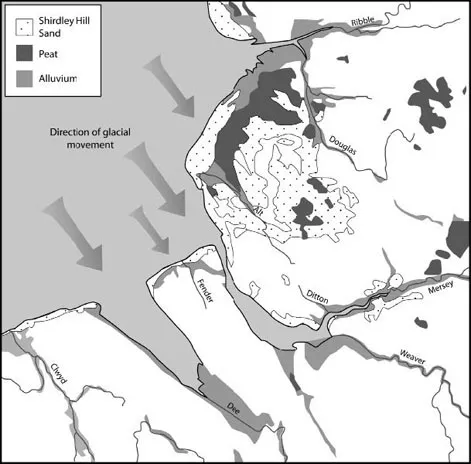

These layers of rock form the foundations of the landscape, but relatively recently (in geological terms) this foundation was carved into new shapes. Around 12,000 years ago the whole of northern Europe was covered in ice up to 3 or 4km thick. It took the form of an expanded polar ice-cap which stretched, at its maximum, as far south in Britain as the Bristol Channel. This thick sheet was incredibly heavy, and one of the effects of the weight of ice was to carve out the underlying geology. As the ice gradually flowed from the Irish Sea basin south-east across the future Merseyside, it carved out parallel grooves from north-west to south-east. The largest of these was the channel of the Mersey itself, but the ice also created the valleys now holding the River Dee, the Fender on the Wirral and the River Alt and Ditton Brook on the east bank of the Mersey.

In very rare cases evidence has also been found which shows that the ice eradicated an earlier, slightly warmer period (known as an ‘interglacial’) when the area of Lancashire was covered in pine, spruce and birch. There have even been finds of hippopotamus and hyena in caves on the edge of the Pennines. These animal remains suggest that Lancashire had seen much warmer periods before the coming of the Ice Age.

One of the earliest processes to influence the landscape, the ice sheet which flowed south from the Irish Sea basin carving out the Mersey, Dee, Weaver, Alt and other valleys. Today this results in a series of parallel grooves running north-west to south-east across the region, shaping everything from early human settlement to Liverpool’s major west coastal position. (After Patmore, J.A. & Hodgkiss, A.G., Merseyside in Maps, p8, 1970, Longman, with additions)

Surface geology

Over the top of these geological layers, ground bare by the ice, we find wind-blown sand, known as Shirdley Hill Sand, which makes up the dunes found along the coast from Crosby to Southport. These were also first laid down as the ice retreated, and can form features up to 15m (49ft) tall around Little Crosby and Ince Blundell, while sand forms the base of hills up to 75m (246ft) further inland in the east of the county. Some of the sand in the area has been found to contain thin layers of organic material, demonstrating that conditions changed over time, switching between wind-blown sand depositions and temporary lakes where the organic material was laid on the lake-bed.

The most recent processes were the laying down of peat, clay and silt which formed damp, boggy moorland in hollows and low-lying areas, mostly in the north and west of the county, and near the Shirdley Sand hills. The two largest areas of this are the Simonswood and Chat Mosses, and these dictated the type of wildlife which lived in the area, as well as later settlement.

The shape of Merseyside

Due to this surface geology the lie of the land in Liverpool is one of rising and falling ridges as you move from the edge of the city, near Croxteth and Kirkby, past West Derby, Queens Drive, Tuebrook and Edge Hill. Some of the other higher areas of the region are remnants of this differing erosion; Mossley Hill/Woolton, Everton Brow, Castle Street and Wallasey/Bidston were eroded less as the ice passed over them. Waves of high and low ground can also be traced inland from the Mersey to the north-east between Parbold and Billinge, each valley’s direction reflecting the original course of the glacial flow.

So, the building blocks of Merseyside are the Triassic sandstone layers on which the city, and a large area around it, sit. Beyond this flat area the Carboniferous slopes of the Pennines and Snowdonia have formed a backdrop for millennia. The ice came later and helped carve out the Mersey, Dee and other smaller rivers in the area, but this uneven weathering left higher ground in ridges running parallel to the Mersey. As we shall see, all these processes, large and small, affected the manner in which Merseyside was first inhabited as the ice sheets gradually retreated. Thus the foundations of Merseyside were shaped before humans settled and began to alter the environment for their own ends.

THE EARLIEST PREHISTORY OF MERSEYSIDE – THE MESOLITHIC

The first traces of humans arriving on the banks of the Mersey come only after the ice retreated. Therefore, whereas many other parts of the United Kingdom have thrown up evidence of human activity up to 500,000 years old (from the Palaeolithic, or Old Stone Age), the remains of the activity of people in the Liverpool area can only be seen in the more recent Mesolithic, or middle Stone Age, around 10,000 years ago.

Movement and settlement

The sea level around this time was around 20m (66ft) lower than it is today. This means that dry land stretched out much further than it does now, with the coastline running from just west of Anglesey to west of Walney Island in Morecambe Bay. A band of now-submerged land around 10-15km (6-9 miles) wide lay between that line and the present coast.

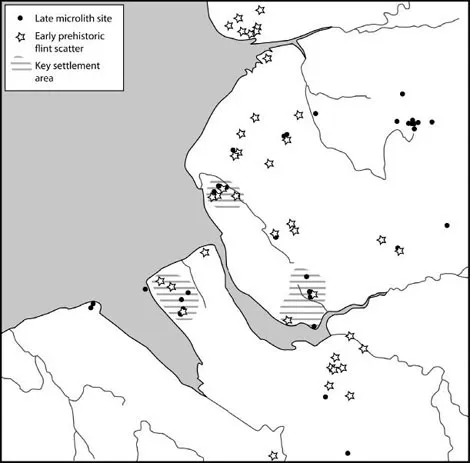

This area was inhabited by small bands of people who moved between residential sites, with smaller locations associated with specialist hunting and gathering activities. These people must have only been seasonal occupants of the land, with a very mobile lifestyle. No evidence has been found for any buildings, but sites at Irby, Tarbock, Crosby and Lathom have revealed toolmaking evidence in the form of microliths – tiny stone tools used as weapons and knives. Ditton Brook was an important location also, and Mesolithic flint tool evidence points to this area being the location of repeated visits by Mesolithic humans. Their tools have been found either on the surface of the boggy layers, or eroding out of the stream bank, and this settlement may have been contemporary with that at Brunt Boggart, where similar evidence for Mesolithic occupation has been found. The pattern which emerges is that of camps along the Sefton and Mersey coast, some of them larger bases from which small groups would move out from. These small groups would form camps where specific activities were carried out, such as toolmaking, foraging or butchery.

Some of the earliest evidence we have for human settlement comes from the Mesolithic era (around 5,000 years ago). There were no permanent settlements – instead, people moved between camps, possibly seasonally, to take advantage of different resources. Archaeological excavations may suggest favoured places which were repeatedly used. (After Cowell, R., 2010, Fig. 16, in Journal of the Merseyside Archaeological Society vol. 13, with additions)

Another centre of activity is the mid-Wirral sandstone ridge. This is one of the ridges less eroded by the ice as it flowed south across the region and was probably drier and better drained than other parts of the peninsula. It was also more suitable for the favoured animals and plants which were hunted and foraged by these early human communities.

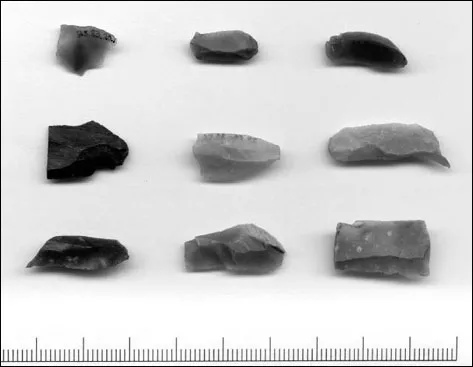

The best Mesolithic site in the region is at Greasby, Thursaston. Here the density of finds is at its highest in the county, with over 200 square metres covered in the remains of the flint toolmaking process. Not far away, at Greasby Copse, excavation revealed stone-lined pits (their function uncertain), and fragments of chert, which was the material used to make stone tools. The chert was shown through analysis to have come from North Wales, so even at this early stage, fairly long distance trade was essential for survival in this flint-poor area. The two sites at Tarbock – Ditton Brook and Ochre Brook – produced groups of stone tools between 50 and 250 pieces, and an excavation at Croxteth Park brought up another 500.

Although archaeological evidence for Mesolithic hunter-gatherers has been found around Merseyside, it is only in the later part of the period that we find clues to the activities of people close to what is now the city of Liverpool. Around 7,000 years ago, as the wetlands in the north-west were spreading and expanding, the earliest direct evidence for human occupation near Liverpool was created on the shores at Formby. Here, preserved in ancient sand layers, are sets of human footprints alongside those of deer, showing that humans were using the zone between high and low tides to hunt large animals.

Tools are some of the most common remains of Mesolithic culture. Known as ‘microliths’ these small (less than 10cm) stone flakes were fitted to shafts as arrow heads, or used on their own as scraping or cutting tools. These tools were discovered during an excavation at Croxteth Park. (Trustees of National Museums Liverpool)

A woodland landscape

The Mesolithic landscape was covered in forest up to 500m (1640ft) above sea level, consisting of oak, hazel, lime and elm. Just behind the coastal zones, and in the poorly drained hollows of the inlands and uplands, fens developed. The remains of these wetter areas give us small clues that humans were active in the area at this time. The surfaces of these boggy mires show evidence of burning, suggesting that perhaps the mixed woodland was being cleared deliberately, before being allowed to grow back. Bidston is an area where clearances look to have been at their greatest. While some of the fires would have been natural, humans would have been able to encourage an increase in the diversity of wildlife in the woodlands through partial clearance of small areas.

In general, the landscape at this time consisted of broken woodlands of oak and hazel, with patches of wetland, and the region was subject to frequent flooding. The land immediately on either side of the river would have been slightly more open, with a mixture of oak, hazel, alder, elm and pine, as well as shorter shrub-like vegetation taking advantage of the increased sunlight of the open land near the water. By 5000 BC, however, most of the land around the banks of the Mersey would have become mixed deciduous woodland, with the bogs and mosses mentioned previously breaking up the tree cover in places, in addition to the small areas cleared by humans.

Gathering food

The people here could rely on the well-stocked river, and the birds and plants inhabiting the banks, for food. There is also evidence for the killing of larger animals – wild pig and deer. The tidal Mersey would have encouraged a wide variety of animals for people to exploit, and the streams would have provided a route into the interior of the county before widespread clearance of woodland took place. The streams would also have provided the clean water needed for living, freshwater fish from the streams as well as saltwater fish from the Mersey estuary itself.

There are several sets of prehistoric footprints preserved in the Formby sands north of Liverpool. The earliest are Mesolithic, and give a startlingly vivid portrayal of a moment in time when humans crossed the beach here. Animal footprints have also been found, demonstrating that humans and wild animals existed in close proximity to each other. (Dave McAleavy Images)

The coastal lands, particularly sites at the mouths of the Ditton and the Alt and at Banks near Southport, have proven rich with Mesolithic material. As well as the variety of fish mentioned above, these areas had small amounts of flint washed up from the Irish Sea bed. It follows that areas near the mouth of the Mersey would have been important centres of population at this time, but these sites, if they existed, have been lost in the expansion of the city.

One of the classic signs of the change from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic is the emergence of farming. However, this distinction is no longer seen as black and white, and pollen evidence found in the Merseyside region shows that cereal-like plants were growing in what we might term the Mesolithic. Although the term ‘cereal-like’ doesn’t necessarily indicate farming as we would recognise it today, it does show that by the end of the Mesolithic new technologies were slowly being adopted. However, other parts of the farming ‘package’ – farming, pottery and permanent settlement – were not yet taken up. Coastal locations, such as Flea Moss Wood in Little Crosby, Martin Mere and Hillhouse, have produced such plant evidence. It may be that connections with other communities around the Irish Sea and even down the Atlantic seaboard, which became so important in later prehistory, were already influencing life on the banks of the Mersey.

One thing we know very little about is the range of ritual beliefs and activities of these people. There is evidence on the European mainland of burial rituals as far back as 225,000 years ago, and it may be that the much more recent Mesolithic communities of Merseyside were performing similar activities, but non...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 From the Earliest Prehistory to the Founding of Liverpool

- 2 From Liverpool’s Foundation to the Civil War

- 3 Civil War and the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

- 4 Living in Liverpool

- 5 Docks, the Port and Industry

- 6 Reshaping the City

- 7 Roads, Rails, Tunnels and Tracks

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Copyright