![]()

1

A NEW THIRST FOR ENERGY

London’s need for power was the result of several major developments in the 1800s and early part of the twentieth century. It was perhaps the most important period in the city’s long history; a time during which London grew in size and stature to become the most vital city on earth, before later being ravaged by the effects of two catastrophic world wars, only to emerge strong as always.

GAS POWER FOR LIGHTING

Gas production was introduced to London in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, and progressed during the beginning of the reign of Queen Victoria. It was an era defined by advancements in technology and science, changes in government both home and abroad, and by the fruits of the Industrial Revolution.

The British Empire grew ever bigger, with each new territory opening up greater trade routes to the rest of the world. The Port of London quickly developed into the largest collection of docks, wharves and riverside factories the world had ever seen, built to handle the huge selection of goods flowing in and out of the city. The success of the docks led to thousands of new buildings being constructed, with many villages and towns becoming absorbed into the capital as its sprawl rapidly increased outwards from the original medieval City of London. The industry that grew in and around the docks provided work for hundreds of thousands of men across London, particularly those from the East End. Many would later lose their jobs in the second half of the century as the docks began to suffer from the first signs of the major decline that would come in the decades that followed.

By the mid–1800s, London was again leading the way at the cutting edge of another major new innovation, this time on dry land. The coming of the railways had a huge impact on the city, with miles of new lines constructed that helped to connect the growing metropolis with the rest of Great Britain. All of London’s most famous railway stations were built in this period, allowing for millions of people to flow in and out of the city every year.

In the early 1860s the streets of London had become such a congested mess that a new system for how people moved around the city was desperately needed. The only solution was to go underground, and it was at this time when the first lines on what would later be called the Tube were opened.

Other industries also developed across the city, including clothing manufacture, flour mills and hundreds of factories. Conditions were often appalling, with thousands of men and women forced to work in factory jobs that in many cases were comparable to slave labour.

Occurring in tandem with the establishment of London’s new industries was the other major social change that defined the Victorian era; a dramatic rise in population that would see millions of new arrivals to London. The growth of industry had created new jobs for London’s workforce. But the coming of the railways also made it easier than ever before for those from other parts of the surrounding counties to move to the city in order to find work. An increasing number of people also began to arrive from all over the world. Each new group of immigrants began to settle in the capital and establish their own communities, starting their own types of industry in the process. The Irish and the Jewish accounted for much of the influx of new arrivals, followed closely behind by those from Bangladesh, India and several other nations.

Other factors that contributed to the population increase included vast improvements to healthcare and medical treatment. A rise in the number of marriages led to more women giving birth, and the medical advancements helped to ensure that more babies survived their birth and early years. At the other end of the life cycle, Londoners were also beginning to live longer. This was partly the result of the better healthcare standards, but also because of the fact that the nineteenth century was a time of relative peace, with no major war on home soil, and no widespread disease outbreak.

The resulting population increase brought millions of new residents to the streets of London. The more people that arrived, the more power was needed to accommodate them. The earliest gasworks, however, produced gas primarily for commercial use only. They were used to supply gas lighting for factories and a range of other different workhouses, replacing the oil lamps of a previous generation.

Class distinction in nineteenth-century London was clear cut, with no middle ground. You were either rich, or you were poor, and most were the latter. Low income rates and the rapid increase in population meant that millions lived in poverty, squeezed into cramped housing along narrow streets. The East End in particular was infamous for its slums and the depravity that such places tended to breed.

Gas lighting for private, residential use was therefore reserved solely for the wealthy during much of the century. Nevertheless, demand did later grow for public street lighting. Its provision by several local authorities across the city helped to lower crime rates, and allowed Londoners to do more in the evening.

By the latter part of the century gas was being manufactured on a massive scale by gasworks across London. The lower prices that mass production offered meant that gas could finally become a realistic commodity for every social class, bringing it directly into people’s homes for use by gas lights and for cooking.

ELECTRICITY FOR THE MASSES

The Victorian era may have been the age of gas, but the twentieth century was dominated by a new form of power. As the new century began, advances in technology and engineering allowed for electricity to emerge as a new way of powering London. Similar to gas, it was first used only for commercial purposes, or in select homes owned by the wealthy.

Shops, restaurants and theatres are just a few examples of businesses that benefited from the foresight of their owners to install electrical lighting. The extra custom it created made such businesses the envy of other traders, and it wasn’t long before there was huge demand for electrical power throughout London.

What followed soon after was a desire felt by everyday people to have electricity piped directly into their homes, first for lighting, and various other appliances in later years. A mixture of private and council-owned power stations were built to meet the expected demand, although it was in fact largely the electrical companies themselves that created the demand in the first place.

Electrical power generation on a massive scale was pioneered in London. Power could now be supplied across long distances and to millions of consumers at once. It was an innovation widely promoted by each electricity company, encouraging people in the city to want it in their homes and places of work.

In the context of today’s society, it is difficult to fathom the concept of electricity being anything other than a basic public service that is always there when we need it. But in its early development it was sold as a product, creating a market that grew in much the same way as the popularity of mobile phones, the internet and other global communications did in the century that followed. It was new, it was sold as a must-have commodity, and everyone ended up wanting it.

The rise of electricity did of course have a detrimental effect on gas manufacture. Electric lighting made the gas lights of old seem archaic in comparison, and it led to serious decline for many gas companies. London’s gasworks still produced a product that was in demand for cooking and heating, although this would begin to disappear by the 1960s.

POWER FOR TRANSPORT

Another increase in demand for electricity came from the continued success of London’s transport system. In the late nineteenth century and early part of the twentieth, electric trains rapidly replaced steam on the Underground network. More and more people were using the Tube every day, resulting in a higher frequency of trains per hour being needed. This called for high amounts of electric power, and with no National Grid at this stage, it was left to the responsibility of the railway companies to generate electricity themselves.

The initial solution was a number of small power stations owned by individual lines, but as passenger numbers increased and companies amalgamated into one network, it was clear that a more suitable long-term plan was required. The outcome was a series of large power stations constructed specifically to power the network, with extra capacity left over to supply new lines like the Victoria and Jubilee that would arrive later. Elsewhere, the city’s tram network also needed powering in the early decades of the twentieth century. This was managed in much the same way as the Underground, with tramway operators having their own small generating plants, before later being powered by the dedicated large power stations. London’s main-line railways also later made the switch from steam to electric traction, which again demanded power from a series of purpose-built power stations across the city.

The success of the Underground network was itself a by-product of London’s continued growth during the last century, both in population and physical size. The first half of the twentieth century was characterised by the devastating impact of two world wars. Yet population continued to rise regardless, especially in the period between wars, when London spread out in every direction, causing its number of residents to swell to more than eight million.

The mass of people, and the products and services they demanded, meant that London was able to avoid being impacted too greatly by the global economic downturn of the 1930s. Rather than suffer decline, many industries continued to grow, among them the electricity supply companies.

By the 1940s, the landscape of London was dominated by large power stations. The British Empire had perhaps lost much of its power, and other cities around the world may have taken away some of London’s status as the centre of the world, but it was still a city on the rise. As technology, youth culture, arts and entertainment, tourism and commerce all continued to grow, so did the need for electrical power. It is a demand that has never eased since. Today, London still requires huge amounts of gas and electricity. Gasworks have been replaced by supply from the North Sea and beyond. The major power stations have all but gone, replaced by more efficient and environmentally friendly plants. But it is still a city hungry for power, a necessity not likely to ever disappear.

![]()

2

BIRTH OF THE INDUSTRY & THE MAJOR PLAYERS

With London’s ever-growing need for power in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it didn’t take long for the wheels of commerce to start turning in unison with the mechanical and industrial developments they began. Demand was high, and it was a demand that needed to be met. Although London’s electricity supply, gas manufacture and other such power-related industries developed at different times and in different ways, the principle was always the same. Scores of different companies started to appear almost overnight, creating fierce competition within each sector, and often mass confusion for the early consumers.

As is usually the case in business, however, many firms disappeared just as quickly as they appeared, allowing a small group of large companies to take control, absorbing everything in their path towards the top. The birth of the gas industry in particular is a tale littered with faded memories of lost companies that were forced to amalgamate with a handful of major businesses. Other companies managed to dominate their industry from the very start, having become established so early that no one else ever really stood a chance of competing against them.

This chapter explores how each power industry emerged, and the major players within them. Many of the power stations, gasworks and other buildings discussed in this chapter still exist, and will be explored in full detail in later sections of the book. Further information about how each power system actually works will also be covered later.

GAS PRODUCTION ARRIVES IN LONDON

Electricity rapidly earned its place as the leading power industry in the latter part of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. But before that there was gas manufacture, a genuine stink industry that came of age in Victorian London.

Its primary use in the 1800s was to provide lighting, specifically by powering gas lights. Although not capable of achieving the same brightness as the electrical lights that would later replace them, gas lights were a vast improvement on the candles and oil lamps that came before them. Instances exist of gas being recommended as a way of powering lights as far back as in the 1680s, suggesting that the basic principle was far from new. But it was only in the early part of the nineteenth century that sufficient advances in chemistry meant that what was once merely theoretical could now become a reality.

There was little demand for public gas supply at first. The early companies that began to operate instead focused their attention on providing lighting for factories and mills. The appeal was simple: gas lights were cheaper, and more powerful and efficient than oil lamps or candles. The lack of a naked flame also provided a safer environment, especially for those factories manufacturing flammable products.

Taking note of how water was already being supplied directly to buildings and houses by way of mains built below streets, the potential for gas to be delivered to consumers in the same way was soon realised. It wasn’t long before the focus of attention shifted therefore from industry to the public domain.

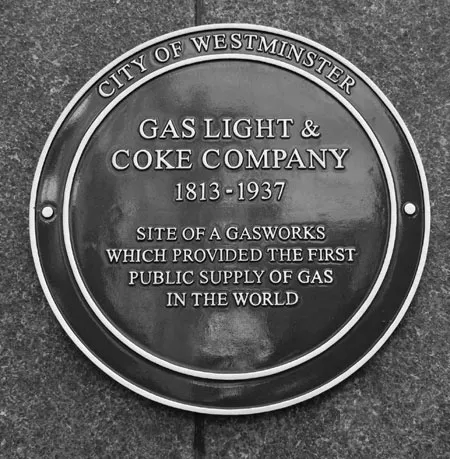

Although London was often surprisingly lacking compared to other parts of Britain when it came to capitalising on new industrial advancements, it was in fact at the centre of the early gas industry. And so it was in London, in Westminster to be exact, where the world’s first public gas supply company was established in 1812 by royal charter. It was called the Gas Light & Coke Company and, quite remarkably, managed to retain its position as the biggest gas producing firm in London until it was nationalised more than 130 years later.

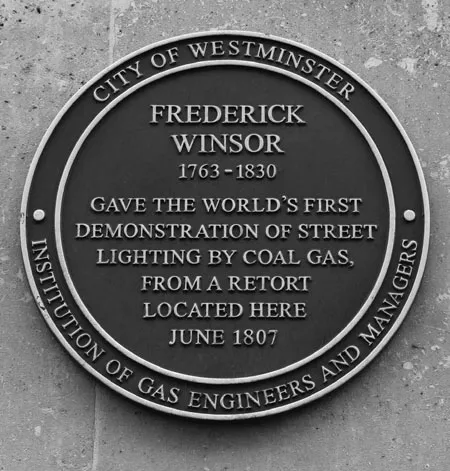

The company owes much of its success and ambition to German inventor Frederick Albert Winsor. Something of a fantasist and unabashed self- promoter, Winsor came to London in 1803 to generate interest in his pioneering work relating to gas lights and their potential for public lighting. Yet even at this point in time, at the very beginning of the century, the concept was not entirely new. It was an idea already being developed in Paris, but also closer to home in Birmingham.

The advancements in the West Midlands were thanks to Scottish engineer William Murdoch. Building on the knowledge gained from reports of wealthy businessmen who had used gas to light their homes, it was Murdoch who recognised the potential for gas lighting to be used in factories. Murdoch was employed at the time by Boulton & Watt, a company whose steam engines had played a significant role in the Industrial Revolution. As a firm already renowned for its innovation, the chance to be part of a new scientific breakthrough made it easy for Murdoch to gain permission to experiment with lighting at their factory in Birmingham.

The experiments proved successful, and by 1803 gas lighting at the factory became a permanent fixture. This was followed by similar installations at various other factories. Murdoch was doomed to become merely a footnote in the history of gas supply, however, thanks to his short-sighted insistence that gas lights would only ever be suitable for industry.

Winsor on the other hand did see its public supply potential, and set about proving it with a series of early lectures and demonstrations, most of which failed to impress potential investors for his proposed National Heat and Light Company. It was a PR campaign that Winsor had already failed at in Paris, but his enthusiasm and persistence eventually started to pay off in London.

The huge potential of Winsor’s idea for using mains to supply gas to the public could no longer be ignored. By 1807 a consortium of investors began a series of moves towards shaping his ideas into a serious business model. The first task was to gather support in Parliament, an exercise that was met almost immediately with opposition. Although the consortium claimed that the new proposed company – now set to be called the New Patriotic Imperial and National Light and Heat Company – was being founded on the notion that it would provide a much-needed public service, the detractors were quick to point out that a lack of competition would lead to a monopoly. One individual figure opposing the new company was Murdoch, a man perhaps more than a little bitter that his early innovation was now on the verge of major financial success without his involvement.

Whatever the motives of those opposing Winsor, the various objections raised were enough to ensure that the company didn’t obtain its charter. Other unsuccessful attempts followed, but the consortium did finally succeed in gaining their royal charter in 1812. Now to be known as the Gas Light & Coke Company, the original plan for a national gas supply had been downsized to London only, but it was still enough to lay claim to being the first company of its type the world had ever seen.

Plaque commemorating Frederick Winsor’s early gas demonstrations.

The Gas Light & Coke Company’s first gasworks in Westminster.

The company opened its head office and first gasworks on what is now Great Peter Street in Westminster. Keen to widen their reach as quickly as possible, the Gas Light later opened two further gasworks in Shoredit...