![]()

1

Buttington – 893

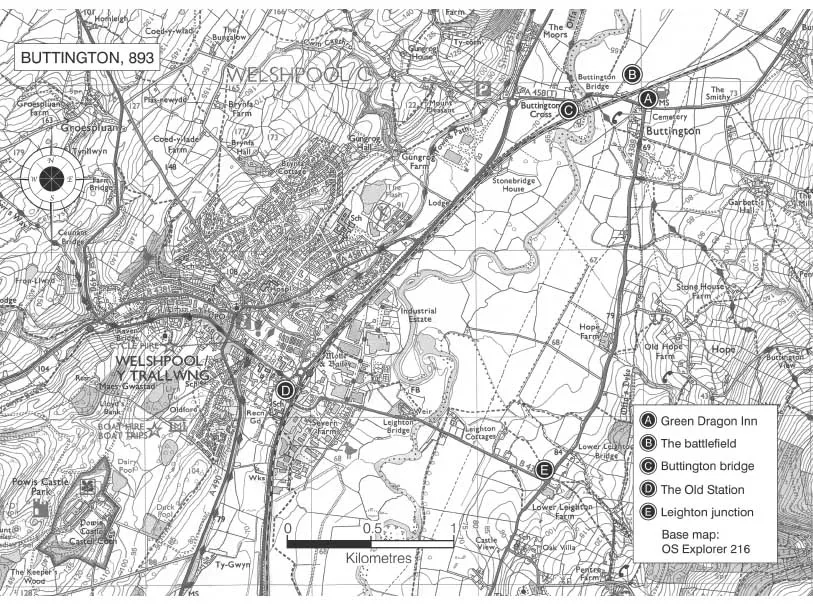

WELSHPOOL, POWYS – OS Landranger 126, Shrewsbury and Oswestry (250 090)

Buttington is a small hamlet situated in the wide plain of the Severn valley, some four miles inside the current Welsh border, and lies close to the modern course of the River Severn. The market town of Welshpool is a further mile to the west, and the important Dark Age monument Offa’s Dyke runs close by. With regard to the majority of Dark Age battle sites, modern historians have little or no written evidence to enable them to identify one location from another. This, when coupled with the lack of archaeological evidence available for those battles fought more than a thousand years ago, makes an exact identification of a battle site even harder. Given the literary and archaeological evidence available, by cross-referencing the entry for 893 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle with the archaeological evidence from the Archaeologia Cambrensis, it is clear that this hamlet of Buttington is the exact site of a long-lost Dark Age battle and, as such, Buttington is a gem among Dark Age battlefields.

PRELUDE TO BATTLE

In 893, King Alfred the Great, ruler of Wessex, was preoccupied with a Danish invasion in the south-west of England. This is supported by evidence elsewhere in the most important written source for this period, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The entry for 893 states that two Danish fleets, with a combined force of 140 ships, were making for Exeter. At this time another Danish force, apparently made up from four different armies, was making its way up the River Thames and then up the River Severn, until it was overtaken by English and Welsh forces at Buttington, near Welshpool. Accordingly, King Alfred sent three ealdormen to gather what men they could to tackle this new threat, which had appeared surprisingly far inland. ‘Ealdorman’ was an appointed and sometimes hereditary title carried by a man who, in conjunction with the sheriff, was responsible for the administration of a shire. Their importance in military terms is that they were also responsible for commanding the armed force of their shire and leading it on behalf of the King, whenever and to wherever he commanded.

At Buttington, the Danes either occupied an existing fort or constructed a defensive position of their own. An English army on the east bank of the Severn, and a Welsh force on the west bank, had by then besieged the Danes for some weeks. This was an impossible position for the Danes because they had no way of escape without conflict and little chance that their supplies could be replenished by a relief force. Accordingly, with their food supplies gone and their numbers and fitness declining, they were left with no alternative but to try and fight their way out. To head west would be suicidal: they would have needed to cross the Severn and fight a Welsh army that had the advantage of ground, and with an English army at their heels. The only logical way was therefore east and back down the Severn valley, but straight into the arms of the waiting English troops. This meant that the Danes would have been facing only one enemy, as the Welsh army would probably have been forced to remain isolated on the far bank of the Severn. It seems unlikely that there was any means of crossing the Severn quickly, otherwise the Welsh would have done so earlier and defended their crossing-point against any Danish attempt to go that way.

Looking from the welsh side of the River Severn towards the mound on which Buttington Church stands, with the schoolroom at the centre of the picture.

RECONSTRUCTING THE BATTLE

It is the author’s belief that at least part, if not all, of this Danish army made its way to Buttington by water. The Danes, in common with other Vikings, were master boat builders and built a variety of differently sized ships pursuant to their requirements. Modern archaeologists have proved that the Vikings successfully traded between Scandinavia, Byzantium and Russia. They achieved this by using the major rivers of eastern Europe and by rolling the ships across the land between these trading rivers, effectively making their boats into land vehicles.

All Danish ships were of shallow draught and capable of moving fast, even when rowed against wind and tide, while carrying not only men but also horses and supplies. These vessels were capable of transporting anything from a dozen to a hundred men, and on some of the ships they would work in shifts, half of the crew resting while the others rowed; this meant that the ships could be kept moving at all times. When they returned downriver, the waterway would carry them and their booty, meaning that the majority of the crew could rest before their return home, whether that was a base on the British mainland or a distant fjord in Scandinavia.

The Severn is known to have been navigable as far as Poolquay, just two miles north-east of Welshpool, until the last century. Wroxeter, located five miles west of modern Shrewsbury, was the key Roman town in Shropshire; in the second century AD it was serviced by Roman craft making their way up the Severn. Indeed the stones from which the church at Wroxeter is constructed carry marks indicating that they were once part of the Roman quay that served the 200-acre site of the city of Wroxeter.

One can imagine the scene. The Danes have rowed against the flow of the river for several days, perhaps raiding or resting up at night depending on the lands through which they were passing. Then they come to a wide-open valley with hills far away on either side. Unknown to them, the rain on the Welsh mountains has swollen the two rivers that meet west of Shrewsbury, the Vyrnwy and the Severn, causing them to burst their banks and flood the valley. The Severn would be the weaker of the two currents at this point and also the wider valley. Noting this fact, the Danes push on, unaware that the course they are now taking is across flooded marshes and not a normal riverbed.

As evening approaches they espy an old earthwork perhaps part of the great Dyke, which has been on their east side for the last few miles. They gather their boats together and use the mound as a base for the night. The Danish warriors are alerted in the night by those on watch, who have seen torches about a mile to the west on the other side of the river. Alarmingly, further torches are seen a little later on, but this time they are on the eastern side of the river from the direction of the hills that the Danes passed earlier in the day. The Danish camp stirs into life, and as dawn begins to break, those on watch are horrified to see that the river has overnight retreated some twenty yards to the west, and it is still visibly falling. The Danish ships, which had been half in and half out of the water, are now resting in tall, sodden reeds and grasses.

With full light, the harsh reality of their situation is brought home to the Danes. Their ships are stuck on sodden ground some distance from the river, a distance that will increase unless more rains come and the river rises again. There is a Welsh army standing on the west bank of the river. Although the Welsh are out of missile range at the moment, if the Danes try and drag their ships to the river they will have to do so in the face of prolonged attack from the arrows, slings and javelins of the Welshmen. Meanwhile, to the east an English army is forming up on the lower slopes of the long mountain ridge behind them. The Danes are surrounded, a long way from their homes and a lifetime away from assistance.

The Severn valley at Welshpool seen from the top of the Breidden Hills, showing the extent of spring flooding.

At this point the Danish leaders must have held a meeting to discuss their options. Do they defend their position while they wait for the river to rise again, and so escape between both armies without having to fight? Or do they risk an all-out attack before more English and Welsh troops arrive? The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that they were ‘encamped for many weeks’, so one can safely assume that the Danes decide to consolidate their force, perhaps rationalising the ships into the minimum number required to get home, and breaking up some of the others. This will provide them with the materials to construct a rudimentary palisade around their camp as well as providing fuel for fires to cook and light their camp by night. As is the way with Britain, the rain does not fall to order and now, though the Vikings probably pray to their gods every day, no rain falls in sufficient quantity to raise the river level.

DARK AGES WARFARE

Battles in this period of history were fought at very close quarters: it was not only the whites of the eyes but the spots, the sweat and the fervour that you saw on your enemy’s face just before your weapons clashed together. This was warfare where death was dealt close up, with perhaps no more than 5 per cent of the casualties being caused by missile fire.

An example of a Dark Age shield-wall provided by various re-enactment groups. (Lucy Corke, Mercian Guard re-enactment group)

An English army of the period would have consisted largely of troops armed with a spear and a shield. Such troops could comprise as much as 80 per cent of the total force, and of these probably only one in four would have a hauberk of chain-mail to wear. Nobles would make up a further 10 per cent of the army: they would be armed with superior-quality mail and a large two-handed axe. Leaders would be similarly armed to the nobles but would have the highest-quality weapons and armour available, and would probably be the only men in the army with helmets. Both leaders and nobles took their positions in the front of the line, looking to engage their opposite number in single combat, if possible amid the confusion of battle. The lesser-armed troops, known as the ‘select fyrd’, would take up their positions in the second and subsequent ranks behind their better-armed superiors. The remaining 10 per cent of the force would be missile troops and skirmishers: these lightly armed troops’ role was to harry and weaken the opposition by concentrating their missiles at a particular point.

The tactics for all armies at this time centred on the creation of a shield-wall with which to assault their enemies. This was a solid mass of men who interlocked shields with the men on each side before fixing their spears at the attack position. Their opponents would be similarly formed, and both sides would chant and shout insults at each other, each force trying to boost their own morale and at the same time weaken that of their opponents. Eventually the two sides would charge towards each other and a huge maul would occur as each side tried to hack and stab their enemy down by sheer brute force. The light troops would try to exploit any gap or weakness that appeared in the enemy lines. If any light troops were caught between the two opposing shield-walls as they closed together, then unless they were able to extricate themselves, either by leaping over or passing round the lines of tightly packed shields, they would simply be caught and crushed in the fight.

As time goes on and some warriors die from disease, hunger or wounds suffered in earlier battles, the Danes continue to rationalise their resources. This is a desperate time for them, trapped and incapable of doing anything save watching the sky for rain, sharpening their weapons for the fight that must surely come if the rains do not, with their belts getting tighter and their bodies weaker as food supplies dwindle.

Eventually the situation becomes so desperate that the Danes decide that they have to try and break out. By now, the weather has probably got much warmer, drying out the land around their remaining boats and indicating that summer is near at hand and that the likelihood of any more heavy rains has passed until the autumn. Almost all of their food is gone, but the Danes need strength to fight their way out. Their only source of fresh food is their horses, so in desperation they kill sufficient of them to feed the remaining men; perhaps, as only one horse head was found in the burial pits, one horse was sufficient to feed the whole force. They plan to break out in the last light of evening, after they have rested all day; this will give them a chance to run through the English lines and then scatter into the darkness of night, in an ‘every man for himself’ situation. Accordingly they have one last meal together, calling one last time on their gods to assist them before they prepare for battle.

Faced with only one course of action the Danes break out of their encampment and assault the English lines. Danish armies only ever contained a few horsemen; perhaps these lead the charge to try and punch a hole through the English lines, followed by the bulk of the Danish force. Perhaps some Danes try dragging a number of the smallest boats to the river to attempt and escape by that route, while the rest of the army holds the English host at bay. The darkness helps to protect the Danes if they advance towards the Welsh army, who undoubtedly watch the battle unfold before them across the valley.

The fighting is evidently fierce as a named king’s thegn, Ordheah, is killed, along with many other English thegns. At this time, a thegn was a landowner with an income of more than four hides per year, whereas to become a king’s thegn meant that the landowner had an income of more than forty hides per year. There is still much debate as to what area a hide covered. A hide is defined as the land necessary to keep one family for a year, and varies on interpretation between 30 and 120 acres. Some of the Danes escape – perhaps those few that had horses left to carry them – but clearly the battle is won by ‘the Christians’ (the English) and there is ‘a very great slaughter of the Danes’ (The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, tr. Dorothy Whitelock, Eyre and Spottiswode, 1961, p. 56). Eventually, when there are no Danes left fighting, their opponents collect their bodies and take the Danes’ weapons, armour and anything of value. Perhaps the English have mounted troops who undertake some kind of pursuit to try and hunt down those few Danes who have succeeded in escaping.

This brings an important question and the most difficult one to answer: that of the numbers involved in this battle. We know from the Archaeologia Cambrensis that exactly 400 skulls and associated bones were found in the three burial pits discovered under the churchyard, but were all of these Danish dead? We know from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that some Danes escaped ‘by flight’, but the word ‘slaughter’ suggests that the majority of the Danes were killed. With this in mind it seems likely that the Danish army was no more than 500 strong, which would make the size of the fleet between ten and fifteen ships depending on their capacity.

The action of the Danes can also provide a clue as to the size of the English army. The Danes adopted a defensive position, which would suggest that their army was significantly smaller than the English. Had the Danish force been anywhere near equal in size to the English then they would have attacked at once, rather than risking the arrival of more English troops and by so doing giving the English the advantage in numbers.

Buttington Church. The burial pits lay underneath the schoolroom, which is at the far end of the churchyard. The ancient yew tree is said to have been planted to commemorate the battle.

At first glance, the Welsh army is even more difficult to gauge, but as it opted not to try and interfere in the battle, choosing instead to adopt a holding position on the far bank of the Severn, it would suggest that the army was smaller than the English, and therefore possibly smaller than the Danish force as well. The advantage of ground may have been sufficient for the Welsh to be sure that the Danes could progress no further west, but it is also apparent that the Welsh army was not large enough for the Danes to be worried about a direct Welsh assault on their own defensive position and stranded ships.

TH...