![]()

PART ONE

MEDICAL MEDDLERS

![]()

1

A MAJESTIC MEDICAL MEDDLER

In consideration whereof, and for the ease, Comfort, Succour, Help, Relief, and Health of the King’s poor Subjects, Inhabitants of this Realm, now pained or diseased: … It shall be lawfull to every person being the King’s subject, having knowledge and experience of the nature of Herbs, Roots and Waters, or of the operation of same …, to practice, use and minister in and to any outward sore, uncome, wound, apostemations, outward swelling or disease, any herb or herbs, oyntments, baths, pultes and amplaisters, according to their cunning, experience and knowledge in any of the diseases.

Herbalist’s Charter

King Henry VIII, 1542

King Henry VIII was fascinated by potions.

Throughout the history of medicine the majority of doctors have based their practice upon the accepted knowledge of the day. Those who do not subscribe to this approach but use unorthodox methods inevitably face being ridiculed by their peers or disparaged as quacks. The word ‘quack’ actually comes from ‘quacksalver’, derived from the Dutch kwakzalver. Originally it was used to describe a peddler in ready-made remedies, but eventually it became used as a blanket derogatory term for anyone who made extravagant claims about their expertise or their treatments.

Another derogatory term that was applied was ‘mountebank’. The origin of this was from the idea that unlicensed peddlers of medicine and nostrums would mount a bench or small stage at fairs or markets in order to extol about their remedies or their skill.

Of course, no one would ever have proudly claimed themselves to be a quack. Over the years, however, within the ranks of those who have been proclaimed quacks there are to be found many eminent people who did good work and whose inclusion was the result of professional jealousy. Such is the case of the great Dr Ignac Semmelweis (1818–65), a Hungarian physician who saved thousands of women from puerperal fever, an almost always fatal condition in the early nineteenth century, when he advocated that all doctors should wash their hands between conducting post-mortem examinations and visiting the midwifery suites. The orthodox profession was outraged at his audacity and he was effectively forced to leave Vienna.

Equally, there are many who attained fame and fortune in the sure knowledge that they were professing information they did not possess, and who offered treatments that they knew to be well-nigh useless.

But before we delve into the murky waters of medical meddling and the world of quack medicine, we need to look a little at the way that medicine has evolved.

HIPPOCRATES – THE FATHER OF MEDICINE

Hippocrates of Cos (460–377 BC) was a priest physician of the cult of Aesculepius. He was the first doctor to attempt to put medicine on a theoretical basis rather than attributing illness to demonic possession or the displeasure of the gods. He formulated the Hippocratic oath and wrote a body of work that is known as the Corpus Hippocratum.

THE HUMORAL THEORY

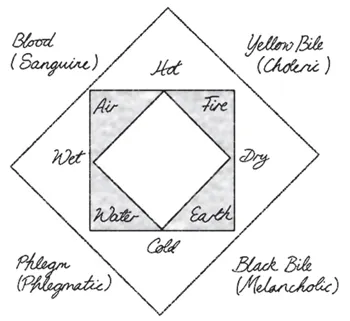

Hippocrates taught the Doctrine of Humors. This became the dominant theory in medicine until the Renaissance. Essentially, it was believed that there were four fundamental humors or body fluids which determined the state of health of the individual.

These humors were blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm. Aristotle had taught that the humors were associated with the four elements of air, fire, earth and water, which in turn were associated to paired qualities of hot, cold, dry and moist. Thus, earth would be dry and cold, water would be wet and cold, fire would be hot and dry, and air would be wet and hot.

The Doctrine of Humors.

GALEN OF PERGAMMON

Claudius Galenus (AD 131–201), known to history as Galen, was a Greek physician who practiced as a physician to a gladiatorial school and was later personal doctor to the emperor Marcus Aurelius. He developed the Doctrine of Humors further and taught that a proper balance of them was necessary for health. An excess of any humor could be treated by reducing a quality, or by reducing a humor, e.g. bleeding the patient or giving enemas, or treating with various Galenical drugs. An example of a Galenical would contain cucumber, which has cooling properties, because it naturally contains salicylates.

The individual’s temperament could also be discerned according to their balance of humors. Thus, sanguine individuals were perceived to have excess blood, choleric individuals had excess yellow bile, melancholics had too much black bile and phlegmatics had excess phlegm. As a philosophical system it had much to commend it and seemed perfectly plausible.

RENAISSANCE MEDICINE

This period saw a spate of scientific discoveries which would gradually discredit the humoral theory. The study of anatomy had been carried out erratically over the centuries, mainly because dissection was considered by the Church to be a desecration and an abomination. Nevertheless, in 1543 Andreus Vesalius of Florence published the world’s first anatomically correct treatise on anatomy. This set off a serious study of the body that culminated in William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood in 1616. Doctors began to realise that blood circulated, but there was no equivalent circulation for the other supposed humors.

Then in 1625, Santorio Santorio, a friend of Galileo, invented the thermometer. This really proved to be the nail in the coffin of the humoral theory since for the first time it could be demonstrated that people with hot or cold constitutions in fact both had the same temperature.

One would have thought that the Doctrine of Humors would just disappear at that point. This was not to be, since its simplicity and plausibility could be put to great use by the medical meddlers during the age of quackery that would follow.

Now let us backtrack a little to the days of the Tudors to consider one of the greatest medical meddlers.

KING HENRY VIII AND THE QUACK’S CHARTER

Medicine in Tudor England was a hotchpotch of medical practice. In 1518 King Henry VIII (1491–1547) conferred a royal charter to found the College of Physicians in London. This was the first attempt to regulate medical practice, albeit only loosely. The College of Physicians was permitted to license physicians to practice.

In 1540 he gave another royal charter to form the Company of Barber-Surgeons, which would eventually become the Royal College of Surgeons in 1800. Its function was to license surgeons.

By granting these two charters, King Henry VIII had effectively given the physicians and the surgeons the social status and recognition that they had sought. The physicians thought themselves to be socially superior to the surgeons, who in turn thought themselves to be superior to the apothecaries and other people who plied a trade. An effect of these charters, however, was that it was seen to give the physicians and the surgeons a monopoly on the preparation of medicines. Poor people could not afford the expensive preparations containing precious metals and minerals that the physicians and surgeons prescribed. Interestingly, Henry had some sympathy for them, for he himself was a medical meddler.

In 1542 he granted the Herbalist’s Charter, which allowed herbalists, or anyone with knowledge to do so, the right to prepare herbal remedies. Since this effectively gave anyone the right to practice medicine without any interference from the physicians or surgeons, it was derided by the medical profession as being the Quack’s Charter.

Undoubtedly, Henry’s interest in herbal preparations derived from self-interest. He suffered from leg ulceration for many years. Whether it was a varicose ulcer or a syphilitic ulcer has been debated by historians for many years. Whichever it was, he clearly tried to treat it himself. Indeed, he is known to have been experienced in compounding ointments and making plasters.

He actually collaborated with several doctors and wrote a book on the subject, containing 130 prescriptions. Many of them actually acknowledge that they were ‘devised by the King’s Majesty’. One prescription for a plaster ‘Resolved Humor If There Is Swellgnje In the Legges’.

Another was devised ‘for the King’s Grace to coole and dry and comfort the member’. It is likely that this and other similar ones were created by him to soothe and salve the king’s own intimate person, his sexual life being an important part of his very being.

King Henry VIII had set the scene with this charter. The real medical meddling was soon to start.

![]()

2

THE GOLDEN AGE OF QUACKERY

Before you take his drops or pills,

Take leave of friends and make your will.

Satirical caution about Joshua Ward’s ‘Pill and Drop’, 1760

The Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 could be said to mark the beginning of the Golden Age of Quackery. It was a period that lasted for over a century and a half and quite naturally merged into what I describe as the Victorian Age of Credulity.

After the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth between 1647 and 1660, during which time even Christmas celebrations had been banned, there was a general relaxing of social strictures. Many doctors started actively seeking patients and building their practices. They were not alone, however, for this was England where it was perfectly legal after King Henry VIII Herbalist’s Charter to practice medicine under Common Law. Accordingly, they found themselves in competition with many unqualified practitioners, many of whom came to England from abroad, claiming that they had been granted royal patronage by King Charles while he had been in exile.

KING CHARLES II AND DR GODDARD’S DROPS

One respected physician by the name of Dr Jonathan Goddard (1617–75), one of the first fellows of King Charles II’s recently created Royal Society in 1660, was not a quack, but he did profit most handsomely from some shrewd business practice with the king, which today would be regarded as highly unethical.

Dr Goddard had been a Member of Parliament, an army surgeon during the Civil War and personal physician to Oliver Cromwell. He was to become a Professor of Physick at Gresham College. He had invented a secret elixir which he marketed as ‘Goddard’s Drops’, advocating their use for virtually everything. King Charles II was clearly impressed with them, for the Treasury warrant book for 16 March 1698 records a payment of £60 ‘to Peter Hume Esq. without account for the purchase of a quantity of Doctor Goddard’s Drops which by the King’s commands are to be sent as a present from his Majesty to the Queen of Sweden’.

His majesty was indeed so impressed that he paid Dr Goddard the s...