![]()

1

In the beginning

Sub-Lt (A) Eric Brown RNVR, in 1940.

The winning Supermarine Schneider Trophy S6B seaplane, 1931.

One of the main catalysts to arouse man’s interest in high-speed flight was the Schneider Trophy series of air races for seaplanes, which took place between 1913 and 1931. The influence of this competition can be gauged from the fact that the first winning speed was 61mph and eighteen years later the last race was won at 340mph.

By coincidence, in the first six months of 1928, the year sandwiched between the first and second of the three victories that gave Great Britain outright possession of the Schneider Trophy, a 19-year-old cadet named Frank Whittle at RAF Cranwell was writing his required fourth term science thesis entitled ‘Future Developments in Aircraft Design’. In that remarkable document Flight Cadet Whittle postulated the possibility of flight at 500mph in the stratosphere where the air density was less than one-quarter of its sea-level value. To meet the power plant needs of such a high-speed/high-altitude aircraft, young Whittle discussed the possibilities of gas turbines driving propellers, but not the use of the gas turbine for jet propulsion; in the latter field he was shortly to lead the world.

In winning the Schneider Trophy, Britain’s greatest asset was not just to be the international prestige it gained, but the nurturing of the genius of R.J. Mitchell, the young designer who worked for the Supermarine division of Vickers-Armstrong Ltd, and was mainly responsible for the superb designs of the S4, S5, S6 and S6B, the latter three being the winning seaplanes in the years 1927, 1929 and 1931. The full potential of these racing machines was shown on 29 September 1931 when the S6B, fitted with a special ‘sprint’ engine, raised the World’s Speed Record by more than 40mph, to 407.5mph. With war looming on the horizon Mitchell went on to develop his Schneider Trophy masterpieces to the pinnacle of the most famous military piston-engined fighter of all time, the Rolls-Royce Merlin engined Supermarine Spitfire, which made its maiden flight on 6 March 1936.

R.J. Mitchell, designer of Britain’s Schneider Trophy winning seaplanes and the incomparable Spitfire.

Frank Whittle, by now a qualified RAF pilot, filed his patent for a jet propulsion engine on 16 January 1930 and it was granted in October 1932. This was all done without any scientific, moral or financial support, and although the Air Ministry was notified it expressed no official interest in the patent. So there was no suggestion that Whittle’s patent should be put on the secret list, and his invention could be published openly throughout the world.

In spite of the frustrations of the next four and a half years, Whittle succeeded in getting his first test engine running on 12 April 1937, but there were difficulties still ahead.

With the prospect of war coming ever closer there was frantic activity in the fighter manufacturing field, mainly represented in Great Britain by the Hawker Aircraft Company’s Hurricane and Supermarine’s Spitfire. Fortunately both products were available to participate in the Battle of Britain, and were a revelation in their handling characteristics, firepower and particularly their performance attributes.

The Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough (RAE) was heavily involved in promoting the advancement of fighter performance and in October 1941 initiated a programme of transonic flight testing with a Spitfire Mark V.

The Mach numbers that could be attained by this aircraft were somewhat limited by its operating ceiling, but were of the order of 0.75 to 0.78. Excitingly enough, although these goings on were highly classified, new words like ‘compressibility’, ‘sound barrier’ and ‘supersonic’ began to appear in aviation magazines and even be heard in crew-room discussions.

Squadron Leader J.R. Tobin, who was CO of Aero Flight at RAE Farnborough in 1942.

By a twist of fate I was shortly to meet Squadron Leader J.R. Tobin, who was CO of Aero Flight at RAE Farnborough where he was involved in the new programme of transonic testing. At the same time I was to learn something of the innovatory reputation acquired by Miles Aircraft Ltd,1 located at Woodley, near Reading.

I had first met a Miles product when I carried out my elementary flying training in 1939 for the Fleet Air Arm on the Miles Magister, which I found a delight for such a task. This story now jumps to 21 December 1941, when I was a pilot flying Grumman Wildcat fighters aboard the escort carrier HMS Audacity, which was sunk by a German U-boat in the Bay of Biscay. I was subsequently on survivor’s leave, when I was recalled by Admiralty telegram to report to the RAE Farnborough to fly the Miles M.20 to assess its suitability as a possible fleet fighter.

I arrived at the RAE on 5 January 1942 and was handed over to Sqn Ldr Tobin, who had been assigned to show me over the M.20, bearing the Serial No. DR616. My first impression was of something that looked a sort of cross between the Hurricane and Spitfire, with a smaller wing span and a more pugnacious nose than either. However, its two striking features were the fixed undercarriage and the bubble type cockpit hood, the latter to become commonplace in fighters, but at that time a rare innovation. The aircraft was of wooden construction and powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin XX engine.

Tobin showed me over the cockpit layout and said I should familiarise myself by flying it for about an hour, and then he would join me in a Hurricane for a spell of dogfighting.

In essence my report to the Admiralty expressed the view that the M.20, although surprisingly nippy in performance, could not match the Wildcat, Hurricane or Spitfire for manoeuvrability and did not offer enough speed performance over the Wildcat or Hurricane to give an offsetting advantage. However, my biggest misgiving was whether the wooden airframe could withstand the punishment of shipborne operations.

The Miles M.20 with its innovative bubble cockpit canopy.

I was reasonably impressed with the M.20, but more so with the Miles design team when Tobin told me the aircraft was designed, built, and flown in 65 days, this being made possible by using Miles Master trainer standard parts, the elimination of hydraulics, and the fitting of a fixed undercarriage. The concept was to offer a fighter capable of speedy production if we suffered heavy fighter losses in the Battle of Britain. Indeed the M.20 had some very attractive advantages in that it could carry 12 × .303 Browning machine guns in the wings, 5,000 rounds of ammunition, and 154 gallons of fuel – virtually double the fire power and endurance of the Hurricane and Spitfire. These hard facts convinced me of the innovative expertise of the Miles team.

Although at that time I knew nothing of Tobin’s involvement in transonic flight testing, just to make conversation over lunch I asked him what he made of the popular subject in aviation journals of the possibility of breaking the sound barrier in the future. He shrugged his shoulders and said that some boffins believed it could not be done, and that was certainly so of propeller-driven aircraft because of the drag of the propeller, but most felt it would be possible with jet or rocket-powered aircraft.

Britain’s first jet aircraft, the Gloster/Whittle E.28/39. It undertook a comprehensive test programme at RAE Farnborough between March 1944 and February 1945.

This gave me great food for thought, because by sheer chance I had witnessed the maiden flight of Britain’s first jet, the Gloster E.28/39, at Cranwell airfield on 15 May 1941, although I did not appreciate what it was at that time.

It happened like this – I was in 802 Squadron, equipped with Grumman Martlet (Wildcat) fighters, at Royal Naval Air Station Donibristle in the shadow of the Forth Bridge, and we were working up for our first operational assignment. But American designed aircraft had only a lap strap for pilot safety restraint and this was not deemed sufficient for arresting deceleration on an aircraft carrier. Modification was arranged to fit a full shoulder harness, but for this to be done each pilot had to fly his aircraft to Croydon airport, outside London.

I took off for Croydon on 14 May 1941 and ran into very bad weather near Lincoln and was lucky to creep into Cranwell before it clamped down. To my amazement the officers’ mess was alive with dozens of civilians, all looking and acting like conspirators, and I was roomed with a Flight Lieutenant Geoffrey Bone, who unknown to me was one of Frank Whittle’s team and indeed was the installation engineer for the jet engine in the E.28/39. He would not be drawn on what was afoot. Indeed it was not till the evening of the next day when the weather improved slightly that I saw the strange propellerless machine for the first time as it was wheeled out of the hangar and finally took off with a whistling noise for a short flight. On landing it was greeted by an RAF officer who was obviously a key player in whatever was going on. This then was my introduction to a machine I was eventually to test fly three years later at Farnborough, and to a man of genius who was the true inventor of the practical jet engine and with whom I was to enjoy an amicable working and social relationship for many years.

Today, when I look back on these past events, I get a strange sense of predestiny – 802 Squadron Wildcats; the E.28/39 historic first flight and the presence of Frank Whittle; flying the innovative Miles M.20 at Farnborough; meeting Squadron Leader Tobin who was to pioneer transonic flight testing at RAE. To my mind there is a clear line of connection running through those events which had an inevitability, culminating in my association with the Miles M.52 supersonic research project.

A rare view of the Gloster E.28/39 being flown by Eric Brown on its last flight on 20 February 1945.

1. Until 5 October 1943 the company was Phillips and Powis Aircraft Ltd.

![]()

2

A big step into the unknown

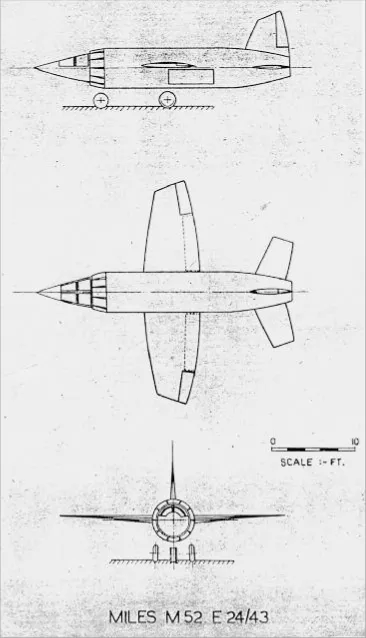

One of the first outline design drawings of the M.52, produced by Miles Aircraft.

My first official appointment as a test pilot was in mid-1942, at about the same time as the magnificent Spitfire Mark IX burst upon the aviation scene. This aircraft, with its two-stage supercharged Merlin engine, arrived at a crucial point in time to provide the increase in performance to match the ubiquitous Fo...