- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Of all the Celtic peoples once dominant across the whole of Europe north of the Alps, only the Scots established a kingdom that lasted. Wales, Brittany and Ireland, subject to the same sort of pressure from a powerful neighbour, retained linguistic distinctiveness but lost political nationhood. What made Scotland's history so different?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Medieval Scotland by Alan MacQuarrie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Romans in Scotland and their Legacy

Although archaeology can throw light on prehistoric societies, the Celts are the first peoples documented by classical writers. History tells us nothing of the Stone Age and Bronze Age inhabitants of Scotland, or of the builders of the unique type of fortification known as brochs, found mostly in the Northern and Western Isles and the north and north-west mainland. It is not until the people of northern Britain came into contact with classical writers that they emerge into history, and even then they are largely seen through the eyes of their enemies.

Ptolemy’s Geographia

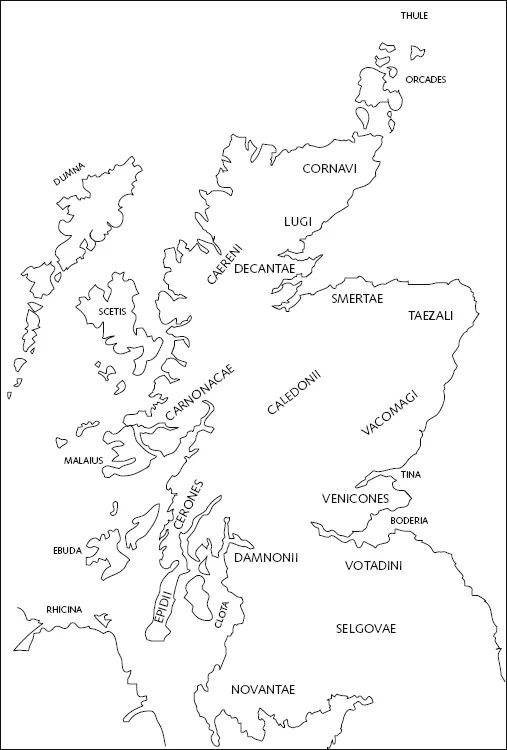

The starting point for any discussion must be the Geographia of the early second-century Greek scholar Ptolemy.1 In his map of north Britain he names a number of rivers and islands which can be identified, and others whose identification is less certain. He also makes northern Britain the home of a number of tribes. It is clear that we should view these tribes as kin-groups presided over and exploited by warrior aristocracies in competition with one another, occasionally forming alliances against powerful enemies. The name of the Caledonii is given prominence in the central Highlands, possibly indicating that some other tribes were subordinated to them.

Much of Ptolemy’s information about the British tribes came from accounts of the campaigns of Agricola, the first Roman general to invade what is now Scotland. Julius Caesar had carried out exploratory raids into Britain in 55 and 54 BC, and Claudius had carried out a full-scale invasion and established Britain as a Roman province in AD 43 and the years following. By AD 78 two major revolts of British tribes had been suppressed and the frontier extended as far north as the Tyne–Solway line. There were major Roman bases at York and Chester to service the army. The stage was set for the campaigns of Agricola.2

Agricola

Julius Agricola was fortunate in having for his son-in-law the historian Tacitus, who wrote a vivid account of his life and campaigns. Before his posting as governor of Britain (AD 77–84), Agricola had previously served there, and was familiar with the terrain and the tactics of the Britons.

Scotland according to Ptolemy, c. AD 140.

In 79 Agricola made his first foray into what is now Scotland, advancing as far as the Firth of Tay. In the following year Tacitus states that he fortified the Forth–Clyde isthmus with a string of forts along the line later to be used for the Antonine Wall, although little archaeological evidence has been found to confirm this. In 81 he crossed the Firth of Clyde (probably from the Roman fort at Barochan near Houston) and explored the west coast, contemplating a raid into Ireland. In 82, ‘fearing a general confederacy of the peoples beyond the Firth of Forth’, he crossed into Fife. As long as his troops had cover from their ships, they were able to cow the enemy; but when they entered the lands of ‘defiles and passes’ of the Caledonii in the central Highlands they ran into difficulties and were forced to withdraw.

During the winter of 82/3 Tacitus says that the Caledonii ‘held public conventions of their separate states, and with solemn rites and sacrifices formed a league in the cause of freedom’. He had previously commented that the Britons were usually easy to defeat because they could not come together in such alliances. The army faced by Agricola in the summer of 83 probably represented the massed might of most of the tribes north of the Forth–Clyde line, led by the Caledonii. Tacitus hints that Agricola was able to keep in touch with his ships as he advanced, so his march must have been close to the east coast. Traces of marching camps have been detected as far as Aberdeenshire, never more than a few miles from the coast. Agricola engaged the enemy on the slopes of Mons Graupius, somewhere in north-east Scotland.

The Caledonii were commanded by ‘chieftains distinguished by their birth and valour, among whom the most renowned was Calgacus’. Calgacus is the first Scotsman whose name is recorded for posterity, and Tacitus attributes to him a suitable speech of exhortation to his assembled troops. ‘We are the men who never crouched in bondage,’ he told them. ‘Beyond this place there is no land where freedom can find a refuge.’ Of the Romans, he says: ‘They make a desolation, and they call it peace.’ Thus inspired, his troops attacked from the higher ground, but the Romans kept their nerve, and in the end the Caledonian army became scattered, and was driven back with heavy losses.

Summer was far advanced, so Agricola was unable to follow up his victory. He made a show of force on land and sea, taking hostages, before withdrawing into winter quarters. The following year he was recalled to Rome; according to Tacitus, the emperor Domitian was jealous of his success. Tacitus talks up Agricola’s triumph at Mons Graupius; but his silence tells us that most of the Caledonian army, including Calgacus, escaped to fight another day. Agricola’s attempt to conquer Scotland had been a failure.

Archaeological evidence fills out this narrative with identifiable places, and confirms that Agricola was indeed an able strategist when it came to positioning camps and forts. Southern Scotland was criss-crossed by a network of roads and forts, at Newstead, Inveresk on the Forth, Barochan near the Clyde and Dalswinton in Dumfriesshire, dominating the southern tribes; the road north from Camelon by Falkirk is more confused. Inchtuthil in Strathmore was intended as a major legionary stronghold to check the power of the Caledonii, and the line of marching camps indicates the route which ultimately led to the battlefield at Mons Graupius. This hill, which has by a misreading given its name to the Grampian Mountains, has not been certainly identified.

Among his achievements, Agricola sent his navy on a circumnavigation of Scotland, thus proving for the first time that Britain was an island. His troops sailed round the Orcades (Orkney Islands) and saw Thule, probably Fair Isle, in the distance. Tacitus does not mention the Western Isles at all, but Ptolemy’s Geographia names several of them in the Oceanus Deucaledonius, the ‘Ocean of the two Caledonii’.

Even had Agricola not been recalled in 84, it is doubtful how much more success he could have expected. His campaigns were not a defeat for Roman arms, but they ensured that Scotland would never be part of the Roman empire. It was decided to retain the Forth–Clyde frontier, with only Inchtuthil as a major outpost beyond. Within a few years this fort too was abandoned, carefully dismantled with more than a million iron nails buried to keep them from the enemy. Some ten years later there is evidence of a major rebellion by the tribes of southern Scotland in which the forts at Newstead, Dalswinton and Glenlochar were burned, and evidence too of a Roman withdrawl to the Tyne–Solway line. In about 120 the emperor Hadrian decided upon a solid stone wall at this point, with a great ditch and mile-castles evenly spaced. It seemed as if the conquest of Scotland had been permanently abandoned.

The Antonine Wall

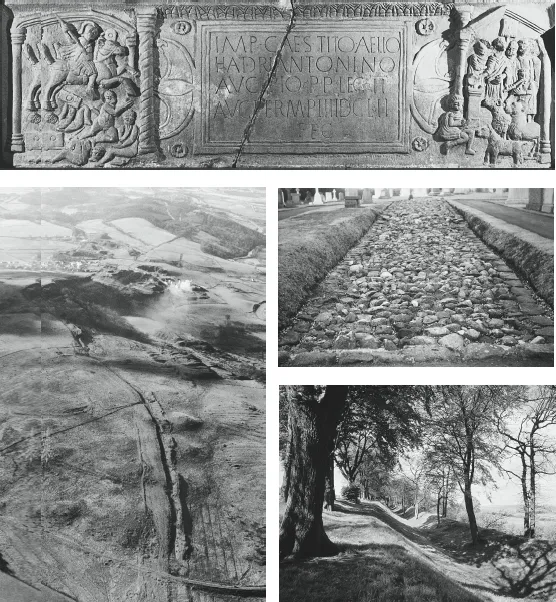

But about twenty years later the Agricolan frontier was recommissioned by the emperor Antoninus Pius, and a new wall was built on the Forth–Clyde isthmus.3 The Antonine Wall consisted of a footing of dry stones covered by a turf rampart surmounted by a timber parapet, with a large ditch in front. The wall ran 40 Roman miles from Bridgeness on the Forth to Old Kilpatrick on the Clyde and was guarded by forts at an average distance of a little over two miles. For the most part it marches across the brow of low north-facing hills dominating the valleys of the Kelvin and Carron. The objective seems to have been to control the tribes whose territories straddled the Wall, and to give the Romans access to the farmlands beyond.

The Late Roman Empire and North Britain

The Antonine Wall seems not to have succeeded in its objective. There is little documentary evidence, but archaeology points to the abandonment of the northern wall c. 155, with one or more brief reoccupations later in the second century. By 197 the historian Dio Cassius described how the Roman governor had to buy peace from a tribe called the Maeatae, who were being aided in rebellion by the Caledonii.4 A decade later the Romans were making progress against their confederation, but not fast enough for the emperor Septimius Severus. In 208 Severus arrived in Britain, carrying out an extensive campaign in Scotland in the following year, and marching so far north that he saw the midsummer sun at night; but he could not bring the Caledonii to battle. By the time he died at York in 211, Severus had fought in Scotland more extensively than anyone since Agricola; but his son Caracalla decided to recommission the Hadrianic frontier. Thereafter the northern frontier of the Roman empire was at peace for almost 100 years.

anti-clockwise from top, the Antonine Wall:

Bridgeness Distance Slab, Bo’ness. (Historic Scotland)

Croy Hill. (Historic Scotland)

Ditch, Watling Lodge. (Historic Scotland)

Stone base of rampart, New Kilpatrick. (Historic Scotland)

Bridgeness Distance Slab, Bo’ness. (Historic Scotland)

Croy Hill. (Historic Scotland)

Ditch, Watling Lodge. (Historic Scotland)

Stone base of rampart, New Kilpatrick. (Historic Scotland)

One name not mentioned until the very end of the third century, although it becomes common thereafter, is that of the Picti, Picts. A writer in 297 mentioned the achievements of Julius Caesar, who conquered Britain when ‘the nation of Britons was still uncivilised and used to fighting only Picts and Irish, both still half-naked enemies’. A clue to the identity of these Picts is found in a poem of 310, which refers in passing to ‘the forests and swamps of the Caledonii and other Picts, neighbouring Ireland or far-distant Thule’. The name Picti appears to mean ‘painted people’, but by the fourth century it had become common for all the people dwelling beyond the Antonine Wall.

A writer in the 360s states that the Picts were divided into two tribes, Dicalydonae and Verturiones. Dicalydonae clearly incorporates the name Caledonii. The Verturiones presumably were Picts living between the Caledonii and the Roman walls. Although the name no longer survives, for many centuries there was a district of Scotland, including Strathearn and Gowrie, called Fortrenn, and this is probably connected with Verturiones. It may be that the pressure exerted by the Romans contributed to a degree of unification of the Picts into these two big groupings.

The peaceful relations between Roman Britain and the Pictish tribes beyond the frontier which prevailed during the third century did not long survive into the fourth. In 306 the emperor Constantius and his son Constantine (later the first Christian emperor) responded to renewed outbreaks of trouble in north Britain by crossing the Wall and marching as far as the Tay; but they again withdrew to the Hadrianic frontier, retaining some fortified outposts beyond. In the 360s the Picts were again attacking the Roman province, and from this time the situation never seems to have been totally restored. In the 380s the northern frontier was stripped of troops by the ambitious general Magnus Maximus in his bid for the imperial throne. By c. 400 Hadrian’s Wall had been abandoned. The last Roman attempt to hold back Pictish incursions into north Britain was by the general Stilicho in 400–2, who returned from the campaign with his legion ‘which curbs the fierce Scot, and while slaughtering the Pict scans the devices tattooed on his lifeless form’.

Thereafter Constantine III made another attempt to seize the imperial throne by withdrawing British troops and leaving the frontier exposed, in 407–11; in 410 the province of Britain was instructed to undertake its own defence, as all available imperial troops were required in other places. In the winter of 406/7 hordes of barbarians had swept into Gaul. That province was in an unsettled state for much of the fifth century; Britain must very quickly have become isolated from Roman civilisation. Archaeology suggests a rapid deterioration in British culture, with coinage for trafficking having gone out of use by c. 430. Britain passed into the hands of local ‘tyrants’ who carved up the imperial province and ruled tribal areas from hilltop fortresses.

Northern Britain after the Roman Withdrawal

There is great obscurity about Britain after the Roman withdrawal, and its degree of continuity with the old province. Germanus bishop of Auxerre came to Britain c. 429 and was met b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Medieval Scotland: Kingship and Nation

- 1. The Romans in Scotland and Their Legacy

- 2. Early Kingdoms and Peoples

- 3. The Coming of Christianity

- 4. The Making of Scotland

- 5. The Twelfth Century

- 6. Reform of the Church

- 7. Economy and Society in Medieval Scotland

- 8. The Thirteenth Century: The ‘Alexandrian Age’

- 9. Scotland’s Great War

- 10. A Changing Society

- 11. The Scottish Church in the Later Middle Ages

- 12. Nadir And Recovery: the House of Stewart, 1371–1460

- Notes

- A Note on Further Reading