![]()

1

PLANT MEDICINE IN BRITAIN

Domestic plant medicine represents the home survival kit. Built up over the centuries, through the daily life of ordinary country people, it has been preserved with remarkable accuracy from one generation to the next. Many human discoveries about the natural world are remarkable. The knowledge of plant medicines must rank as one of the most important in terms of survival of the species. How was this knowledge gained? Was it all empirical, or did our forebears possess a greater instinctive knowledge of food and medicines, akin to that still seen in animals? Horses and cattle will seek out particular plants to eat when they are ill; domestic dogs eat grass to make themselves sick when they have stomach problems. Arthur Stanley Broome, recalling his working days in Norfolk, tells us

On Saturday mornings in the springtime, I have been in charge of a flock of ewes and lambs grazing the roadside banks and fences. The herbs the ewes ate were considered a great benefit to their health and of medical benefit too to help them get over lambing quickly.1

One elderly Norfolk man who was a shepherd all his working days told me how sheep normally avoid eating ivy (Hedera helix) leaves, but will seek these out if they are ill. If there was no ivy available in their field, he would offer them a bunch: ‘If a sheep won’t eat ivy, you may as well cut its throat.’2

Ewart Evans reported the observation of a Suffolk horseman that horses seek out the bark of certain trees when they are ill: ‘They whoolly liked to eat some trees. I’d watch ’em going to the hedge and see what trees they’d stop at. Some of my horses used to strip the bark off an oak and some would take to the ellum. Chance times I used to give ’em some of the bark grated up in their bait. It used to make their coats shine like satin.’3 A Norfolk countryman observed that, ‘if a bed of nettles in the corner of a meadow were mown and left lying for twenty-four hours, horses would eat the nettles eagerly, and benefit from them as from a tonic medicine.’4 Recent work in Dorset suggests that Amazonian woolly monkeys, even in captivity, seek out the most appropriate herbs from those available to treat their own ailments.5

Many people are familiar with the spring-time craving for fresh fruit and salad, which in physiological terms makes good sense; during a long winter, it is easy to become short of vitamin C. Possibly the strange food cravings experienced by many women during pregnancy fall into the category of vestiges of an earlier more strongly developed knowledge of the food and tonic value of plants. Such knowledge was handed down orally from one generation to the next, to become part of that precious commodity, common sense. Plant remedies were modified and ‘honed’ by experience: they had to be accurately remembered and passed on, since otherwise toxic plants, or toxic parts of plants, could have been used with very serious effects. In the eighteenth-century records of the Presbytery of Peebles there is an account of a murder case brought before the Kirk session. Isobel F. was accused of murdering her husband, by doctoring his ale.

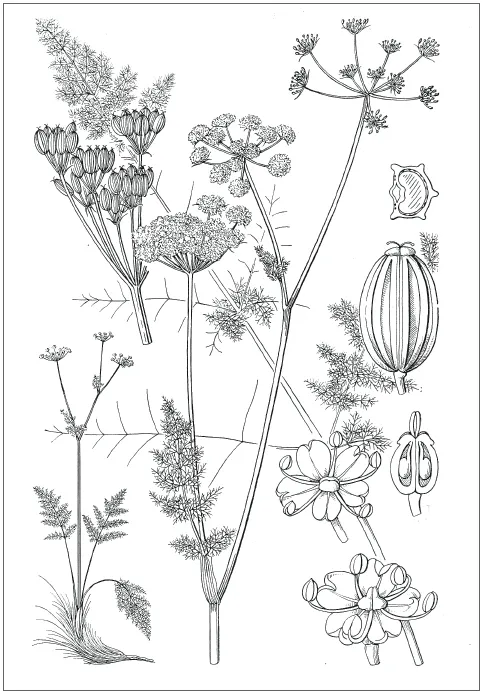

She denied everything, except that she sent to the gardener’s wife at Linton for some herbs, viz. Badmonnie (Meum athamanticum) and fumitory (Fumaria sp.) and thereafter implored her aunt, Mary F., to go to Ingistone for the herbs or any other place where she may get them, and that she brought them from Dolphinton. But she had no bad dealing in seeking them, but was advised that they were proper for her condition’ [she was pregnant]. Will Gray his wife said that Isobel sent to her for badmonnie, but she said she had it not.6

Luckily for Isobel, the case was considered unproven.

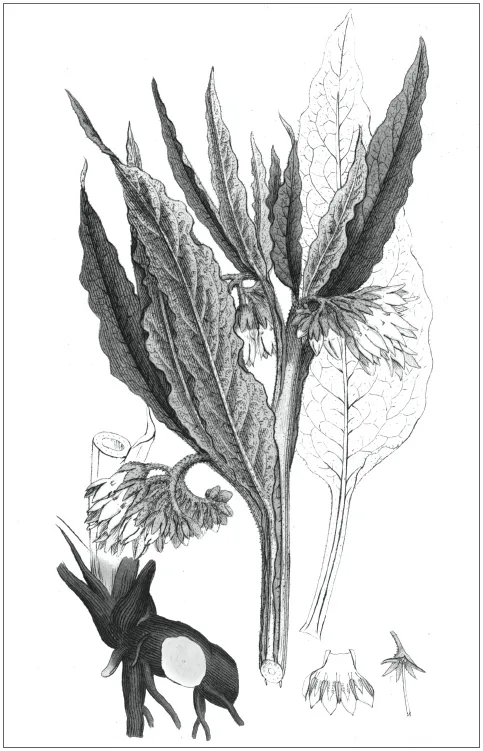

This story illustrates the fact that there was a general awareness of the misuse as well as the use of herbs in medicine. Although it was rarely written down, even in relatively recent times, common knowledge of plant medicines must have been accurate to avoid catastrophes. An interesting example of this is provided by comfrey (Symphytum officinale), a plant used medicinally since the days of the ancient Greeks. In very recent times, doubt has been cast upon the safety of its use. Substances toxic to the liver have been identified in the leaves, and the popular press has made much of the dangers of this traditional plant remedy. What is of great interest is that traditionally the root, and not the leaves, of this plant was used in plant medicine. When I mentioned the use of a tea made from the leaves of comfrey to a Romany friend, he was scandalized that anyone would use the leaves; the root alone was safe to use, and this (to him) was common knowledge, far preceding in time the modern pharmacological analysis. Used in its traditional way, this remedy is perfectly safe, but modern ‘secondary’ use of the plant was inaccurate. The common-sense approach to plant medicine, used as part of people’s everyday lives, included an awareness of which parts of a plant it was safe to use. People did not regard this as specialist information, but took it for granted as common knowledge.

Badmonnie (Meum athamanticum) From Stella Ross-Craig, Drawings of British Plants (by kind permission of the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew/photograph courtesy of John Innes Foundation Historical Collections)

For this reason, when I was collecting data on twentieth-century plant remedies, many people initially disclaimed any knowledge of the subject. If, however, I asked, ‘What did your mother do for you when you were ill as a child’, very often a great deal of information emerged. This is in no way a denigration of its value, more a reflection of how essential a part this knowledge played in people’s lives. Clifford Geertz has defined common sense as ‘a loosely connected body of belief and judgement, rather than just what anybody properly put together cannot help but think’.7

It is, he suggests, more than a recognition of things as they are, it involves ‘how to deal with a world in which such things obtain’.8 Before the advent of medicine as a profession in this country, a working knowledge of plant medicines was, quite literally, a vital part of this body of common sense. The great anthropologist Evans-Pritchard’s description of the Azande could equally well be applied to the country people of Britain, at least up to the present century. They ‘have a sound working knowledge of nature in so far as it concerns their welfare.… It is true that their knowledge is empirical and incomplete and that it is not transmitted by any systematic teaching but is handed over from one generation to another slowly and casually during childhood and early manhood, yet it suffices for their everyday tasks and seasonal pursuits.’9

Knowledge of domestic medicine was handed down orally and, even after the invention of printing and the rise of literacy, very little of it was ever written down: by definition, it is knowledge used by the least literate. Yet oral testimony can be remarkably accurate, sometimes more so than the written word, which is subject to copyists’ errors, misinterpretation and misrepresentation. Too often a writer has a point to make and will be selective in the information he uses to illustrate that point. Oral testimony may be highly accurate, but it rarely provides a complete picture for posterity; as the generation which used a particular knowledge dies off, so that knowledge dies too unless passed on to the next generation, or recorded in some way. I have frequently come across fragmentary knowledge of twentieth-century plant remedies; someone may remember a particular plant being used, but cannot recall how it was used; another may remember how to make a remedy, but cannot recall what it was a remedy for. This process accelerates as soon as a particular remedy is no longer in current use.

Comfrey (Symphytum officinale) From Sowerby’s English Botany (Photograph courtesy of John Innes Foundation Historical Collections)

There is no motivation for the users of domestic medicine to record their remedies in writing. What few records there are on the subject have usually been written by people with no direct experience of country remedies. Such writing tends to treat fragments of information as curios, of a rather quaint nature, to be collected together like a collection of dried butterflies. This not only removes the information from its context, it also tends to lead to a condescending attitude towards the users of such remedies.

The very word ‘folk’ has come to have a patronizing ring to it, and too often accounts of folk medicine concentrate on the bizarre and the fanciful. Taken out of context, and sometimes even quoted quite wrongly, this has built up a picture of folk medicine as a collection of odd anachronistic rituals, practised by the ignorant and superstitious. In reality, domestic medicine was a necessary tool for survival, and still is in many countries. It represents the essence of plant wisdom of many centuries, and it is our loss if we dismiss this wisdom too lightly.

The reasons for the lack of written records of domestic medicine were simply that there was no need to write down such common knowledge, and its practitioners often could not read or write. Simply because of this, their memory was much more retentive than is ours today. It is well known that the less an ability is used, the less efficiently it functions. Today we are so used to depending on the written word that there is no strong motivation for committing large tracts of information to memory. In the past, country people were more at one with their surroundings than we are today. Many could tell the time very accurately without a watch, and predict the weather without listening to radio forecasts or recording pressure changes. The use of plants for medicine as well as for food was part of this greater attunement with the environment.

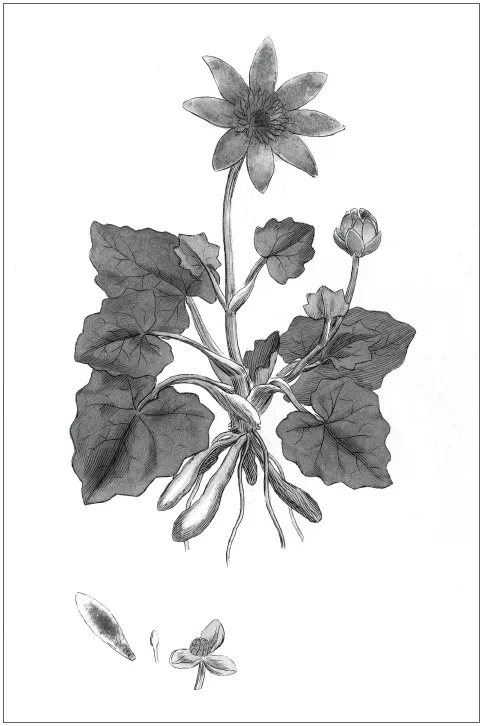

In order to remember which plant was used for which ailment, it seems likely that a system of mnemonics was developed. It was found that lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) relieved piles; the tuberous roots look vaguely like piles, so as well as giving the name pilewort to the plant, the bumpy roots could serve as a mnemonic. This seems to me a much more convincing explanation of many of our common plant names than the so-called ‘doctrine of signatures’. This famous doctrine was first proposed by Paracelsus in the sixteenth century. It is highly significant that he was himself a physician; like all the literate men of his day, he wrote at several removes from the ordinary common people and their ordinary daily life and ills. He suggested that every plant was ‘marked’ with its own medical use, resembling either the part of the body to which it should be applied or the symptoms of the disease which it could cure. This so-called doctrine of signatures was expounded by various seventeenth-century English herbalists, such as William Coles and Nicholas Culpeper.10

Pilewort, lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) From Sowerby’s English Botany (Photograph courtesy of John Innes Foundation Historical Collections)

Once committed to print, information takes on an authority which it does not always deserve. An anecdote from Norfolk will serve to illustrate this. Jack was born in 1900, and all his working days he led a shire horse stallion around the farms of Norfolk to serve the mares. He spent his life very largely with his horse, often sleeping alongside it in a barn. A local farmer, knowing of my interest in old remedies, had lent me an eighteenth-century book on farriery, and in this I had read that it was customary, in order to ensure that the mare fell pregnant, to beat her with a bunch of stinging nettles [Urtica dioica] before the stallion arrived. I was curious to know whether this practice survived into Jack’s lifetime.

I felt shy and awkward with Jack, and foolish because I found it difficult to understand his very strong Norfolk accent and vocabulary. I told him of what I had read in the old book on farriery. His whole face creased up with laughter, and he laughed until the tears made runnels down his grubby face. When he had recovered sufficiently to talk, he told me, ‘They books, they get it all wrong! You beat the mare after the stallion has been!’ (which of course, in physiological terms makes a lot more sense).11

The doctrine of signatures may represent another prime example of a case where the books got it wrong! Might it not be the case that Paracelsus, and others following his written lead, misinterpreted an already well-established and well-used system of mnemonics, well known to the country people who actually made up and used medicines from everyday plants? The berberis (Berberis sp.) was not good for jaundice because it had yellow bark: its yellowness, like a jaundiced complexion, was a feature of the plant by which to remember its medical use. Once the doctrine of signatures was invented by the literate class, it became embroidered and might well have led to some misuses of plants; so that, by extension, all yellow plants might be thought good for jaundice. This idea is explored further in Chapter 5.

Domestic medicine was a common-sense collection of first aid worked out by instinct, by observation of animals and by trial and error, and, at least until the advent of printing, preserved entirely by word of mouth. With the advent of printing came an entirely new chapter in the history of plant medicine. Once committed to print, whether accurate or not, one particular remedy would be preserved and copied from one century to the next. As long as remedies were actually in use, there was little danger of their becoming inaccurate; once they fell into disuse, and particularly once they appeared as reported remedies in print, the situa...