![]()

1

Introduction

From the beginnings of horticulture, growers have tried to improve their orchards and gardens by choosing and keeping the productive or desirable trees. At first, there were merely stands of seedling trees, either natural or planted. Each tree was different from the others, as usually happens when plants are grown from sexually produced seeds.

Eventually growers discovered how to make almost exact copies of their superior plants. One way is by taking cuttings. Put simply, you cut part of a shoot from the original plant and stick it into the ground where it grows some roots.

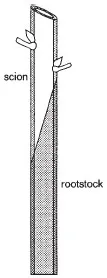

Another way is by grafting. Once again, you cut part of a shoot from the original superior plant. In grafting, this part is called the scion. You then attach this scion to another plant of the same sort (the rootstock) in such a way that the two unite and grow together. Shoot growth from the rootstock is discouraged, so that the scion grows to become the trunk and branches. The rootstock, as the name suggests, provides only the roots and perhaps a short part of the lower trunk. These asexual methods of reproduction are called vegetative propagation. The cuttings, and the scion portions of plants made by grafting, are clones of the parent plant.

Figure 1. A graft consists of a rootstock and a scion.

These days, commercial fruit and nut trees are nearly always propagated vegetatively from selected varieties, as are many important ornamental plants.

Plants produced in this way maintain all of the characteristics for which the variety was selected, such as better fruit yield and quality, desirable form, flowers and foliage, and resistance to pests and diseases. By contrast, seedlings of most plants are inherently variable. Even if the parent plant is a selected variety, its seedlings will vary in crop production and quality from one to another and will rarely equal the parent plant in all aspects. A further disadvantage of seedling fruit trees is that they often take much longer to first crop.

To make a graft, the rootstock must unite successfully with the desired scion. RJ Garner, in his Grafter’s Handbook (see Further reading), described the formation of the graft union as ‘the healing in common of wounds’. This healing in plants begins with the formation of scar tissue or callus, produced either from the plant’s cambium, or from nearby immature wood and bark cells. The cambium is the thin (cylindrical) layer of cells between the bark and wood, where annual growth originates in woody plants. Whenever a scion or rootstock shoot is cut, the cambial layer is exposed along the cut surfaces where the wood meets the bark. All grafting techniques must achieve intimate contact between the cambial regions of the scion and stock, so that they can grow together.

Figure 2. A seedling sweet orange rootstock plant suitable for budding.

Compatibility between rootstock and scion exists only between plants of the same species or closely related plants. Seedlings of the same species as the scion are often used as rootstocks. Seedlings are cheap and easy to produce and sometimes have better root anchorage than cuttings.

However, seedlings are variable, so increasingly, rootstocks are also propagated vegetatively as cuttings. For many major crops, rootstocks have been selected for resistance or tolerance to soil-borne problems such as fungi and nematodes, different soil types, drought, and waterlogging. Once compatibility has been considered, the rootstock can be chosen, independently from the scion, to suit the planting site.

Most modern fruit varieties (and some ornamental plants) are propagated by grafting selected scions onto selected rootstocks. However, a few species such as grapevines, figs, olives and some roses grow successfully as cuttings and are propagated commercially in this way.

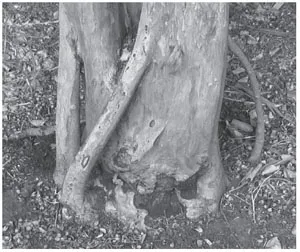

Figure 3. A crepe myrtle accidentally ringbarked by a line trimmer was saved by bridge grafting. Shoots arising below the ringbark were grafted under the bark above the ringbark.

This book describes techniques of budding (bud grafting) – where the scion is a single vegetative bud with only a small piece of stem attached – as well as grafting, where the scion is a length of shoot bearing one or several vegetative buds.

The goal of the grafting process is to form a union between the tissues of the scion and those of the rootstock, followed by suppression of any shoot growth from the rootstock, so that the scion becomes the new aerial part of the plant. The success of the operation depends on having a rootstock in prime condition, selecting quality scion wood and using the most suitable technique for budding or grafting. The timing of the operation and correct after care are also important ingredients for success.

In the 1970s, the CSIRO Division of Horticultural Research (now CSIRO Plant Industry, Horticulture Unit) established a wide range of tree fruit species at test sites throughout Australia. This book describes the techniques used for propagation of these various deciduous and evergreen species. It provides examples of the selection and storage of scion wood, the timing and techniques of the budding or grafting operation, and suggests a timetable for each step of the procedure.

The techniques described in this book are widely used in the commercial production of grafted plants. Home garden enthusiasts can also use these methods to multi-graft their fruit trees, thus making best use of their available space.

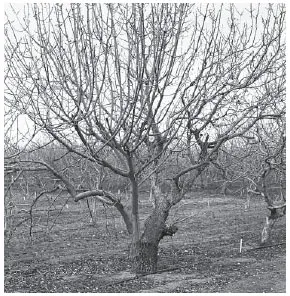

A multi-grafted tree consists of several scion varieties worked onto a single rootstock. Generally, different plants that are closely related may be grown on a single rootstock, such as most citrus varieties, most stone fruits, or a selection of pome fruits. Similarly, different cultivars of a single species can be grown on one tree by budding different varieties to different branches. For example, a range of peach varieties grafted on one tree will mature their fruit from November to March in southern Australia.

However, scions for multi-grafting should be carefully selected to ensure success. If virus-free scion wood is not available, virus or virus-like diseases may cause stunting and interfere with the balanced growth of the tree.

Figure 4. A multi-grafted male pistachio tree.

Figure 5. The essential tools for grafting.

In addition, you should choose scion varieties that have similar vegetative vigour, or else the strongest variety will soon overgrow the others.

![]()

2

Grafting – the basics

The essential tools you will need for budding or grafting are:

- secateurs for making rough preliminary cuts;

- a very sharp knife for making the grafting cuts;

- some suitable binding material, such as plastic budding tape;

- some wound sealant, or scion covers, such as small plastic bags.

Professional grafters have special budding or grafting knives, but you can use any knife of a convenient size and shape. Knives with disposable or replaceable blades avoid the need for sharpening. Be careful when using sharp tools, and check that your fingers are out of harm’s way before making cuts.

The grafting cut

Well-made grafting cuts result in flat, smooth cut surfaces of stock and scion that will lie together with maximum contact, especially where the cambial layer is exposed. For many grafting and budding cuts, you will need to move the knife towards your body, an action that contradicts the usual safety advice for handling sharp knives. You should draw the knife through the wood with a slicing action, rather than trying to push it straight through (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Making a grafting cut.

If you are an inexperienced grafter, you should practise your cuts on some prunings of the intended scion or rootstock.

- Take the knife in your dominant hand, with the sharp edge facing your body.

- Hold the scion (or support the rootstock) with the other hand, on the far side of the point of attack.

- Lay the knife blade flat on the nearest surface of the shoot, diagonally across it.

- Position the blade on the shoot so that the handle end of the blade is at the desired starting point.

- The knife should now be in such a position that the butt of the handle is closest to you, and the tip of the blade is facing diagonally away. The angle between the sharp edge of your knife and the shoot will be 30–60 degrees, with the blade still flat on the surface of the shoot.

- Raise the back edge of the blade slightly from the surface of the shoot to allow the cutting edge to bite into the bark.

- Make the cut by drawing the blade along, through the shoot, and at the same time across the shoot, so that the length of the blade is used, moving from base to tip as you cut through the shoot.

- Make the whole of the cut in one smooth stroke. Stopping or sawing will inevitably result in a rough or jagged cut.

Figure 7. Paring off a thin slice to improve a grafting cut.

Often it is easier to get a good flat cut on the second try, when you are only paring off a thin slice rather than cutting through the full stick. Therefore, you should start by cutting the scion or stock just a little longer than you want it.

Scion wood

Take scion material from sources that are true to variety, that have superior performance, and if possible, from plants of known good health. Always select solid shoots that are well exposed to sunshine and avoid weak, shaded shoots. If you cut scion wood from a grafted source tree, watch out for rootstock suckers.

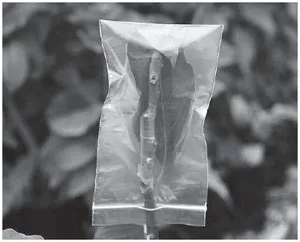

Figure 8. An avocado scion protected from drying with a plastic bag.

It is best to collect and use scion wood on the same day, but you c...