![]()

1

VIKINGS, NORSEMEN AND NORMANS

The Duchy of Normandy emerged in the tenth century out of the region known in the post-Roman era as the Breton or Neustrian March, an area which occupied the western edge of the decaying Frankish, or Carolingian, Empire. Neustria meant ‘New West Land’ in contrast to Austrasia (East Land). It was the inhabitants of Neustria who first used the term ‘Francia’ for the Western Kingdom of the Carolingian Empire. ‘Frank’ was derived from the old Germanic word for members of the tribe on the Rhine which conquered the country that became France. According to the rather scanty surviving historical records, the legal origins of Normandy date from 911 when a Scandinavian warlord called Rollo, or Hrólfr, was created Count of Rouen and granted the lower Seine valley by Charles the Simple, king of the western Franks. Before this, there had been Viking activity in north-western France for at least the previous half century, during which time towns, villages and monasteries were plundered in just the same way as eastern and central England was being regularly attacked on the other side of the English Channel. Evidence of Viking settlement in Normandy during this early phase has been difficult to identify, but it seems likely that there had already been some Scandinavian colonisation in the region before 900. The Franks used the word ‘Normand’ to describe the Viking peoples and this word soon came to be synonymous with the region taken over by Rollo and his Scandinavian followers.

THE CAROLINGIAN EMPIRE

The Carolingian Empire had extended over much of modern France and Germany and had reached its greatest extent under the Emperor Charlemagne, after whom it was named. Its capital was at Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) in Westphalia. The Carolingian Empire inherited many of the administrative structures of the Roman Empire on which it was loosely based, but it extended far to the east of the Rhine, the conventional northern European frontier of the Roman world. In the late eighth century, the Carolingian Empire appeared to be about to reconstitute the pan-European empire of the Romans, particularly after Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day 800. This event effectively marked the beginning of that curious but persistent medieval phenomenon, the Holy Roman Empire, which continued to mould together the fragmented Germanic world throughout the Middle Ages.

Charlemagne was an imperialist who extended his military activity into Saxony, into Muslim Spain where he created the Spanish March, into northern Italy and into central Eastern Europe. The Franks were anxious to claim for themselves what they could of the Roman legacy and this meant bringing architectural styles to Aix from Ravenna, where the late Roman imperial court had left a more dramatic architectural and artistic legacy than in Rome itself. The Carolingian Empire, however, did not have time to take root before it began to fall apart. The governance of such a vast and complex empire proved cumbersome and only partly effective, yet there were strong elements within it which were to serve as models for many of the medieval successor Christian kingdoms of the west. Essentially, however, the empire lacked the military base of its Roman predecessor and proved to be too large for its rural manorial base, and following Charlemagne’s death in 814 it began the long, familiar process of disintegration, the inevitable fate of all empires in the fullness of time.

The Carolingian Empire was made up of a patchwork of principalities under the control of counts, viscounts and dukes. Initially these were closely tied to the Emperor and held their power directly from him. In the early stages there were few hereditary dynasties within the Empire, but by the middle of the ninth century the extended empire proved too cumbersome to be managed from a single centre and was again divided into three: in effect, Germany, France and the Middle Kingdom (Lorraine, Burgundy and Lombardy). These constituent principalities became increasingly powerful and they themselves evolved into semi-autonomous separate sub-kingdoms. Principalities such as Burgundy, Aquitaine and Septimania (Toulouse), while still acknowledging the Emperor’s sovereignty, were able to operate with an ever-increasing degree of independence. These sub-kingdoms were ruled over by dukes (duces) and princes (principes). In the tenth century, the great duchies began to fragment into their constituent counties. In the north of France, in addition to Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Maine, Blois and Flanders all became important principalities under the control of counts. The royal lands, which were, effectively, the residue of the Carolingian Empire, contracted to the area around Paris and Orléans.

In addition to this internal fragmentation, the successors to the Carolingian Empire faced external threats from the Scandinavians in the north and west, the Bretons in the west and, to a lesser extent, from the Muslims in the south. After establishing a bridgehead in Spain in the early eighth century, Muslim forces rapidly took over most of the Iberian peninsula and moved north of the Pyrenees into Francia, where their advance was eventually stopped at Poitiers by Charles Martel in 732. Subsequently, the Muslims withdrew from the north-west of the Iberian peninsula and from the area immediately to the south of the Pyrenees to consolidate their activities in the rest of Spain. Nevertheless, although the Muslims’ hold on mainland European territories was on the decline, partly as a result of their own civil wars, they were still extremely active in the Mediterranean and retained control of all the major island groups, including Sicily, which provided them with a base to attack and settle in the relatively weak Byzantine-controlled areas of southern Italy. They were also able to establish a foothold at Fraxinetum, which was not finally extinguished until 973.

THE VIKINGS

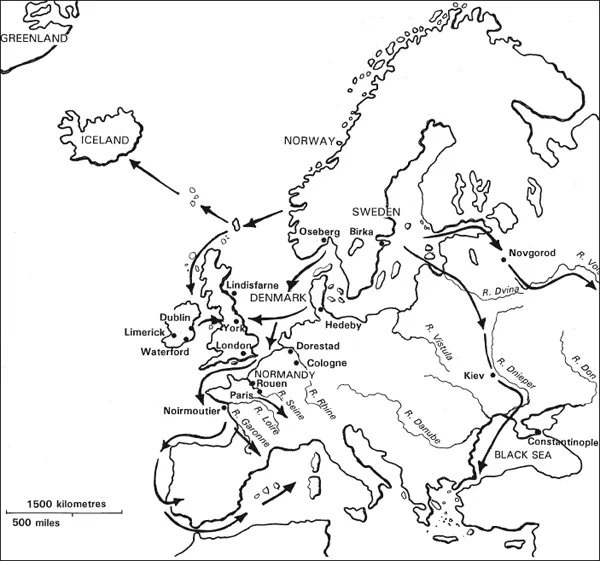

To the north were the Scandinavians or the Vikings who, during the first Viking Age, put an indelible imprint on the political and demographic geography of Western Europe, most notably by the establishment of the Danelaw in north-eastern England and the creation of Normandy in the north-west of France. The Vikings have been traditionally portrayed as pirates: merciless barbarians who plundered and burned their way through Western Europe, intent on destruction and pillage. This deep-rooted popular prejudice about the Vikings can be traced back directly to contemporary ecclesiastical chroniclers who, because they were the custodians of much portable wealth, were frequently the first victims of Viking raids. It could, however, be argued that the Vikings simply represented an unwelcome new player in a crowded political world which had already demonstrated a considerable degree of ruthless violence, particularly against pagans (2). Charlemagne himself had laid Saxony to waste in order to convert it to Christianity, and similar examples of comprehensive premeditated ferocity are common to the whole Norman story.

2 Map showing Viking invasion routes in Western Europe, the western Atlantic and the Mediterranean

THE VIKINGS IN BRITAIN

The riches of churches and monasteries were obvious and easy pickings for the seaborne early pagan Vikings. In 793 the island monastery of Lindisfarne, off the Northumbrian coast, was plundered. On hearing of this attack, Alcuin (d.804), the Northumbrian monk-scholar then working at the palace school at Aix which he had founded for Charlemagne, wrote expressing his horror at the event: ‘it is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such a terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made’. He went on to imply that Charlemagne might secure by ransom the return of ‘boys’, i.e. noble children offered by their parents to the monastery, who had been carried off to Denmark. In 794 another Northumbrian monastery, probably Jarrow, was looted, and in 795 Iona was attacked. The first raid in Ireland was reported near Dublin in 795, and by 799 the raiders had reached as far south as the mainland European coast of Aquitaine. Although Scandinavian invaders and settlers had been involved in Western Europe on a modest scale from the fifth century onwards, the ‘Viking Age’ proper started in the last decade of the eighth century.

Settlement as well as plunder often followed acquisition of land; in this way Greenland, Iceland and the Scottish islands were colonised in the second half of the ninth century. Yet when the Vikings arrived, these were largely empty lands where there was little opposition to their settlements. It was a very different story when their activity was directed against the politically sophisticated and culturally settled lands of Western Europe.

In the first instance, the Vikings’ overriding interest was in portable wealth, usually precious metals, and this made churches and towns particularly vulnerable since the former were frequently used as treasuries for the regions surrounding them. Inevitably, this meant that initial Viking visits to England and, later, Normandy were characterised by violence. Within years such raids were replaced by a form of ‘protection-racket’ throughout western Europe, with a tax called the Danegeld being levied on Christian kingdoms in order to buy off the Scandinavians. Frankish and English rulers made ad hoc payments in the ninth century, but the whole process became more systematic in England after the defeat of the English at Maldon in Essex in 991. Enormous sums ofmoney were raised and paid to the Danes during the latter half of the reign of King Æthelred, and the system of levying geld was refined and made more efficient under pressure of the need to meet escalating Danish demands. The use of geld to support Viking fleets and trained elements in the army led to ambiguity in the use of the word, but the term Danegeld persisted in general use in England until the middle of the twelfth century.

Some scholars point out the more positive aspects of Viking activity: they came in relatively small numbers to begin with and the later phases of Viking incursion were associated with peaceful settlement. The results of the excavations of Viking York (Jorvik), for example, are often used to demonstrate a thriving, industrious, and peaceful urban community, with trading links throughout Western Europe. It is certainly true that by the eleventh century the Scandinavians were operating in much more conventional political and military ways than their predecessors, but the Viking reputation for brutality was more difficult to transform.

In 851 a Viking army made the first attempt to winter in England, in Kent. Some 14 years later, in 865, the ‘Great Army’ landed in eastern England, when a Danish force came with the deliberate purpose of territorial conquest. The ancient kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia were quickly conquered and a Viking territory was established in northern England, which eventually developed into the kingdom of York. Soon, East Anglia and most of Northumbria were under Danish rule, and Mercia was divided between the Saxons and the Danes. Effectively, only the southern kingdom of Wessex remained English. The whole of England might well have been overrun by the Vikings but for the determined defence of Alfred the Great of Wessex (871–99). Alfred defeated the Vikings at Edington (Somerset) in 878, and the resulting political accommodation with Guthrum led to the departure of a large Viking force to northern Francia, allowing Alfred to undertake an ambitious defensive strategy which resulted in Wessex annexing areas of Mercia, including London.

Alfred and subsequent Saxon monarchs devised and developed a defensive system against the Vikings, firstly in the form of a navy and secondly with a series of fortified river crossing towns known as burhs. Some of these fortifications were newly erected at places such as Wallingford (Oxon) and Wareham (Dorset), while others at centres such as Bath and Winchester re-used existing Roman defences. In fact, the ninth-century burhs represented the first systematic campaign of communal defence construction since Roman times. In England, the network of fortified towns created by Alfred and his successors helped revitalise urban life by providing safe locations for the transaction of trade and commerce. By 886 Alfred had made peace with Guthrum, and Alfred’s son Edward the Elder had conquered all the Danish-held lands south of the river Humber. Saxon victories in England marked a crucial turning point in the history of the Vikings’ relations with western Europe since, for the first time, a serious check had been imposed on their activities. The Vikings became aware that there were limits to what could be achieved by their traditional raiding activities in England. The military resistance in England resulted in the diversion of those Vikings who wished to continue raiding across the Channel into western Europe, thereby intensifying the pressure on the lands remaining under the control of the Frankish kings.

Alfred’s success opened the way for a series of attempts to integrate the Vikings into western European life. The Treaty of Wedmore, agreed with Guthrum in 878, had sought a modus vivendi with the Vikings on the basis that he and his followers would, in return for their territory, keep the peace and convert to Christianity. This was a pattern of compromise frequently adopted to contain Viking forces, particularly in Francia. There were, indeed, significant advantages in this type of agreement for beleaguered native rulers, because, in theory at least, the Vikings’ appetite for land was met, but confined within defined territorial limits. Also, the Viking poacher was obliged to turn gamekeeper by taking responsibility for maintaining order in the conquered lands; it was thus hoped to tame the Vikings by integrating them into the existing governmental and religious establishments.

THE VIKINGS AND THE CAROLINGIAN EMPIRE

In the second half of the ninth century the Vikings turned their attention to the great river estuaries of mainland Western Europe, in particular the Rhine, the Somme, the Seine and the Loire, which allowed access into the very heart of western mainland Europe. Even before Charlemagne’s death, Viking raids along the North Sea coasts had presented the empire with formidable problems, and despite the revival of Frankish military strength epitomised by the growth in the strength of their cavalry, the Empire was ill-equipped to deal with maritime enemies. The first Viking ships arrived off the coast of France c.820, and by the middle of the ninth century Scandinavian incursions into France had become an annual occurrence. As early as Easter Sunday 845, the Viking leader, Ragnar, is said to have moved up the Seine to attack Paris. It is reputed that the emperor Charles II, ‘the Bald’, paid him 7000 pounds of silver to leave peacefully and to take his plunder with him.

Specific involvement in the region that was to become Normandy began when it was recorded that the Vikings first entered the Seine estuary. The abbeys at Jumièges and St Wandrille were sacked in 841, and it is recorded that the latter paid 26 pounds of silver for the release of 68 prisoners. There was an escalation of Viking involvement in northwestern France when they overwintered in the Seine valley for the first time in 851. Reputedly, two bishops of Bayeux, Suplicius (844) and Baltfrid (858), were martyred by the Vikings, and c.855 the Scandinavians captured the regional capital of Rouen. It is symptomatic of the havoc that the Vikings were able to inflict on the vulnerable monastic institutions along the Seine, which were the chief chroniclers of early Viking activity in the region, that the accounts of events ceased in the second half of the ninth century as the monasteries themselves were suppressed.

For more than a century the Danes attacked the Empire; not only in its weaker outlying territories, but also in its heartlands, in the valleys of the rivers flowing into the North Sea and in the Loire Valley, where the Frankish traditions of the Empire were strongest. It was here that the monasteries were thickly planted and, enriched by two centuries of royal patronage, presented an almost irresistible target for the Vikings. The imperial family’s political troubles after Charlemagne’s death did not help to co-ordinate resistance to the new enemies, and even the energetic emperor Charles the Bald (861–2) was reduced to employing one band of enemies to fight another. The invaders’ skill on the water, their surprise attacks and their ability to operate in small bands made them difficult for the Franks to deal with except at a local level, and it was here that the imperial government was at its weakest.

The Franks did not respond in the same way as the Anglo-Saxons to Viking attacks; there is, for instance, little evidence of a co-ordinated use of defensive works. Some linear earthworks, such as the Hague Dyke which extended across the northern Cotentin peninsula, were constructed or reinforced, and defensive earthworks of one form or another sprang up across the region, but there appears to have been no systematic network of defended towns as found in England. The invaders were not faced by the co-ordinated resistance which developed under the auspices of the Wessex monarchy in the later years of the ninth century. Despite the energetic efforts of some of the Carolingian kings, effective defence was increasingly organised independent of the monarchy. What this actually involved in terms of the types of fortification to be found in the territory which was later to become Normandy is an area where archaeological investigation has only just begun. The persistence of the raids and the progressive dissolution of the powers of the Frankish monarchy meant that both the kings and the local men who were in the process of acquiring authority began to offer political compromises similar in character to the Treaty of Wedmore.

Other embryonic Norse colonies in the lower Loire and in Ireland failed. Normandy was thus by far the most successful of the European mainland ‘colonies’, several of which had already floundered before 911. One of these, on the lower Weiser, lasted for less than 30 years (826–52), another in Frisia around Walcheren survived for just over 40 (841–85). A colony at Nantes planted in 919 was eliminated in 937. Only in England had dense Viking colonisation in the Danelaw enabled the Scandinavians to bring about a major change in the history of the whole country, but even here it was not because it survived as an independent political unit. Normandy alone survived several political and military crises to become one of the major feudal principalities within the old Frankish kingdom.

THE BRETONS

There were other threats to the empire in the west. Flanders had been created as a result of military expansion by Count Baldwin II between 883 and 918, from a much smaller base given to his father, count Baldwin I, by King Charles the Bald, and was developing into a potential threat to the empire. Even more significant was the danger from Brittany. Brittany, for most of its history, enjoyed a separate existence from mainstream France and had never been fully absorbed into the Carolingian Empire. The Bretons, with strong Celtic roots, were ethnically distinct from the Franks, but their close proximity to the empire meant that they were heavily influenced by Frankish customs and i...