![]()

1

NORTHUMBRIA: A BRIEF HISTORY

Quam cito transit gloria mundi. (How quickly the glory of the world passes.)

(Thomas à Kempis, The Imitation of Christ)

The Dark Ages2 are full of obscure kingdoms that briefly rose to power, only to sink slowly – or catastrophically – back into oblivion. What makes Northumbria worth writing about rather than Rheged, Lyndsey or Elmet, or any number of petty kingdoms that have been swallowed up over time?

And yet Northumbria is different. Its kings were no less violent; its battles were as often ignoble and rapacious as glorious and decisive; and its peasants have left as little a trace as peasants have elsewhere. The kingdoms of Britain in the early medieval period were no different from their inhabitants’ lives: nasty, brutish and short.

While we grant that Northumbria was a relatively short-lived kingdom, and its wars were certainly nasty, one look at a page of the Lindisfarne Gospels will reveal that it was far from brutish.

On the contrary, perhaps because of the sheer fragility of civilised life, beauty became all the more precious. A monk might spend six weeks working on a single letter, only to have it lost to fire, while a smith might hammer a sword blade 10,000 times and then see it shatter as a result of the quenching process. Beauty was something hard won, and harder still to preserve. But in the brief period of its heyday, in conditions that are as perfect an example of a Hobbesian world as one would not wish to find, Northumbria’s inhabitants made a civilisation that stood shoulder to shoulder and eye to eye with Byzantium (the eastern, enduring arm of the Roman Empire) and the new power of the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne.

It might be hard to imagine that kings who could not read and whose preferred method of dealing with an inconvenient relative was assassination, might be bulwarks of civilisation, yet they were. For a brief time, little more than a couple of centuries, an extraordinary kingdom flourished, creating islands of culture in the land by the sea.

The kingdoms of Britain and Ireland in the seventh century. There may have been others, too short lived to leave any historical trace. Wikimedia Commons

TWO BECOME ONE

Northumbria, as it became called, resulted from the forced union of the neighbouring kingdoms of Bernicia, centred on Bamburgh in Northumberland, and Deira, which had its heartland in Yorkshire, centred on York, which was known at the time as Eoforwic. As Northumbria, the kingdom became the most powerful in the land, with at least two of its rulers powerful enough to be known as Bretwalda, high king of Britain. But tensions between the old Bernicia and Deira ruling families ensured that there were always plausible alternative claimants to the throne. When you add one of the peculiarities of Anglo-Saxon kingship into the mix – if you weren’t constantly bringing new petty kingdoms under your control and scattering the largesse of battles won among your followers, then those followers would slowly drift away to rival courts and kings – and combine this with the lack of an established system of precedence, then you have a recipe for terminal instability. It took an extraordinary personality to hold things together at all and Northumbria had a supply of these for a while. But then, inevitably, factional fighting and the renewed strength of rival kingdoms, Mercia in particular, led to Northumbria’s decline. The decline turned into a fairly rapid fall with the arrival of the Vikings, who annexed the Deiran half of the kingdom in AD 867 and turned the Bernician rump of Northumbria into a dependent earldom.

However, the Northumbrians were still sufficiently sure of their ancient rights to self-determination to prove a major irritation to Harold Godwinson’s attempts to claim the throne for himself after the death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066.

Unfortunately for Northumbrian independence, Harold lost to William, and after a number of failed attempts to pacify the north, the Conqueror decided to destroy its powerbase. The record of the Domesday Book, compiled some sixteen years later, is a grim testimony to how thoroughly his troops despoiled Northumbria. That pretty well marked the end of the kingdom of the north, although the earls of Northumberland continued to play a major part in British history, most notably when Hotspur rebelled against Henry IV in 1403. The fifteenth-century Wars of the Roses were also principally northern affairs, with both the houses – Lancaster and York – once having been part of the kingdom of Northumbria.

DARK BEGINNINGS

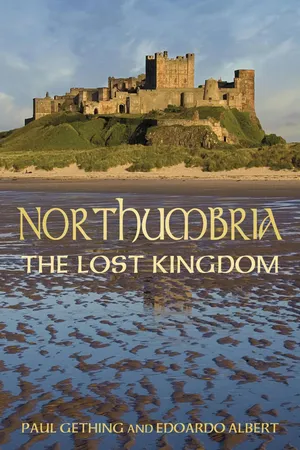

Historically speaking, we know next to nothing about what happened in Northumbria after the withdrawal of the legions and the foundation of the kingdom. This is traditionally dated to 547, when Bernicia was founded by a travelling warlord and his band of merry plunderers. Ida, an Anglian adventurer, spotted the potential of a huge isolated craggy rock by the sea – Bamburgh. Generations, stretching back to the Stone Age, had seen its defensive possibilities. The basalt rock, and the succession of strongholds upon it, command the coastal plain. In those days the sea washed right up to the base of the rock, ensuring easy communications up and down the coast and making a siege all but impossible to maintain.

Ida and his men took the stronghold that was already in place, presumably killing or driving out the previous British king of the area.3 What happened then? The most honest thing would be to say ‘we don’t know’, and move on to other matters. But hey, this is a book on archaeology: we’re not going to let a lack of historical sources stop us speculating about what did and didn’t happen!

Exactly how many men Ida had with him is impossible to say, but it was enough. Enough to hold and consolidate his new kingdom, to fight off the attempts by the native British to take back their land4 and enough to be able to pass it on to his heirs. Ida’s achievement is all the more impressive given that the British were well organised, had several strongholds, including Edinburgh, and were capable of fielding armies, if the sources are to be believed. Strathclyde was still a large kingdom in its own right. The Angles, on the other hand, would have had to cross the sea to call on reinforcements. In any case, the early kings would have had only family allegiances to draw on, since fealty was normally only given once a king had proved that he was actually worthy of being a king. So Ida and his sons and followers probably carved out their realm with limited resources and little or no back up.

It is not until Æthelfrith, some fifty years and, according to the king list, seven rulers after Ida – which gives a good idea of the short tenure of a king at that time – that we reach firmer historical ground.

It was Æthelfrith who conquered the neighbouring Anglian kingdom of Deira and brought Northumbria into being, turning it into a real player in the power struggles of sixth- and seventh-century Britain.

But what of the other half of Northumbria? What of Deira? Unfortunately, if the origins of the northern half of Northumbria are dark, those of its southern end, Deira, enter the realm of mystery. One of the few sources we have is the History of the Britons, ascribed to Nennius,5 a Welsh monk, and probably written in the ninth century. The problem here of course is that this is so much later than the events we are interested in. To give a rough comparison, it would be like relying on a contemporary book for news of what happened during the French Revolution.

Of course, our most important written source is Bede, the author of the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and one of the most remarkable men of Northumbria’s flowering. He wrote the Ecclesiastical History in AD 731, which puts him somewhat closer to events, and undoubtedly his accounts of the later history of the kingdom are the best evidence we have.

Gildas, writing from the perspective of the Britons who were being slowly pushed out of the east and into the west of the country, is our earliest source, probably writing his Ruin of the Britons in the sixth century. According to him, the Anglo-Saxon invaders first arrived as paid mercenaries, hired to fight by British kings who no longer had the services of the professional armies of Rome to call upon. But the mercenaries stayed and gradually started carving out kingdoms for themselves in what became England as the original Britons were pushed west and became the Welsh. But almost everything Gildas says must be taken with a pinch of salt as his account is loaded with his own agenda.

When Augustine, the missionary sent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the English, reached Canterbury in 597 there was an English king ruling in Deira. The genealogy of the kings in the History of the Britons gives a list of predecessors to the kings of Deira and Bernicia, and both lists terminate with the god Woden. But even assuming the king list is accurate, it still gives us no more than a bald list of names begatting other names for the crucial foundational years of these kingdoms.

So what really happened?

This is the question that has exercised generations of historians and archaeologists. It is in this interregnum between the fall of Rome and the pagan English converting to Christianity that the legends of Arthur originate. But of course, the once and future king was warchief of the Britons in their struggle against the invading Anglo-Saxons – the leader of the (soon to be) Welsh against the English! Ultimately, the Britons lost and the English won, pushing the Celtic peoples into the extremities of the island – Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. But what remains an open question is how much this national transformation was brought about by mass migration and how much by a change in the ruling elite.

HISTORY RESTARTS

From our vantage point, nearly a millennium and a half after the events we’re going on to describe, one major problem remains the predilection the Northumbrian ruling families had for beginning their sons’ names with a vowel, in particular O and Æ. It can be difficult to separate Oswald from Oswiu from Oswine, or Æthelfrith from Æthelwod and Ælfwine in one’s mind. It’s hard not to think that these were dynasties in desperate need of an injection of consonants.

There is a complete list of the kings of Northumbria here, with their dates of reign (as far as these can be attested). But the story of the kingdom is not the same as the story of the kings; some of them can simply remain as names on the list, with nothing more said. But after Ida, the first king we must speak of is Æthelfrith, traditionally the eighth king of Bernicia and the first to rule Deira as well.

Æthelfrith became king of Bernicia around 593. From about 604 he was also king of Deira, thus uniting under him the constituent kingdoms of Northumbria. It is with him that history restarts; an ironic destiny for an illiterate warrior who was one of the key figures in driving the still literate and Christian Britons out of what became England.

In the desperate Darwinian struggles of the sixth century, Æthelfrith proved a master. Bede records him inflicting a devastating defeat on the Scots in 603, ensuring, according to Bede, that no king of the Scots attempted to attack English land again up until Bede’s own day, some 130 years later. With Deira annexed the following year – we don’t know how it was done, whether by force, persuasion, intimidation or some combination of the three – Æthelfrith turned his attention on the Welsh, winning a crushing victory over them around 615.

At the time, the victory must also have seemed a triumph of the old pagan gods over the new Christian God, for as a prelude to the actual battle, Bede tells us that Æthelfrith ordered his warriors to attack and slaughter the Welsh monks who had come to pray for their side’s victory.

This victory established Nort...