- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Searching the archives of the university, the Public Record Office, the Centre for Oxfordshire Studies, this work collects more than 100 accounts that paint a picture of Oxford's seedier side. Using court records and newspaper accounts, it brings together crime stories dating from 1750 to 1920, including: infamous murders, hangings, and more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oxford: Crime, Death and Debauchery by Giles Brindley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FIGHTING, RIOTING AND DUELLING

SOCIAL STANDING

In 1235 Henry Le Ferur was dragged by Adam Feteplace, trader and several times Mayor of Oxford, into the latter’s house and beaten. Henry charged Adam with assault and the robbery of a gold ring. Unfortunately the judge stated that the charge Henry made in court was not exactly the same as the one he had made at the time of the assault; Adam was acquitted of all charges. However, the jury concluded that Adam had beaten Henry and thrown beer in his face . . . hardly what you would expect from a former Mayor.

TIT-FOR-TAT

Considering the tender age of some of Oxford’s undergraduates, especially during the early history of the University, it is hardly surprising that it was often handbags at five paces. Ferriman Moore, a Balliol scholar, was charged in June 1624 with assaulting John Crabtree of the same college. Moore pleaded not guilty, but was convicted of homicide and manslaughter, having stabbed his fellow college member in the stomach. Moore pleaded the benefit of his status as clergy and applied to the King for a pardon.

It appears that during a snacktime in college the two had squabbled. Then, as now, there was often some fierce marking of territory between graduates and undergraduates. Crabtree, 20, a graduate, chastised Moore, 16, for presuming to drink with him, threatening him, kicking and then pulling Moore around by his hair and ears. Moore had left the buttery and headed for his rooms, but Crabtree followed. A brawl ensued and in the confusion Moore stabbed the other man.

The magistrates took pity on Moore, and his punishment was reduced to burning in the hand – quite common at the time – because Moore had pleaded his status as clergy. Since the magistrates expected a full pardon to follow, and because they feared the student may leave his studies, the sentence was reduced to nothing.

It did not work out as quite expected, as Moore presently disappeared. A year later he mysteriously reappeared and recommenced his studies at Exeter College.

RETURNING THE FAVOUR

During the Civil War Oxford was a royalist stronghold, but not before the parliamentarians were driven out soon after the royalist victory at Edgehill in October 1642. As the soldiers left, one of the London troopers, marching down the High Street, let rip at St Mary’s (the University church) and in particular at the statue of Mary above the porch, blowing off her head and that of baby Jesus.

But favours came from both sides when, later, some Christ Church aristocrats stopped the coach of the elderly Lady Lovelace (a Whig) outside the Crown and pulled her from it, calling her an ‘old bitch’. Even the Dean of Christ Church was forced to express displeasure with the students.

INCIVILITY IN CIVIL WAR

During the early years of the Civil War, when Oxford was held by the royalists, one Captain Hurst was executed by firing squad in December 1643, by order of the King, for having stabbed a superior officer during an argument. The sentence was carried out in Mr Napper’s ancient Great Barn, which stood across the road from his house, Holywell Manor.

DEAD MAN’S WALK

In 1645, towards the end of the Civil War, Cromwell routed a party of the King’s troops near Islip Bridge; 200 soldiers and 400 swordsmen were taken at this crushing defeat and the rest fled to Bletchington Park. Cromwell followed and besieged them there. The governor of the Bletchington Park garrison was Colonel Francis Windebank. Against his better judgement, but at the request of his wife and other women, Windebank made a deal and surrendered. Bletchington Park was one of several outposts that were intended to keep Oxford supplied and protected from sudden attack. The colonel was allowed to return to Oxford with his colours to report the surrender to Prince Rupert who, having just been humiliated at Islip, was rather less than pleased with the news. Windebank was brought before a court martial and taken to the meadow wall of Merton College and shot. To this day the path is known as Dead Man’s Walk.

NORTH–WEST DIVIDE

Battle commenced between Exeter and Queen’s colleges in mid-February 1665, between those from the north and those from west, which was unusual as battles were fought normally between north and south, but each to their own.

MONMOUTH VS YORK

Charles II died in 1685 and two men stood to gain by being crowned king: his illegitimate son, the Protestant Duke of Monmouth, and his brother, the Catholic Duke of York. Less than two years before, in 1683, tension was running high in Oxford, as elsewhere. In April 1683 it was only two months before the Rye House Plot (the plan to assassinate Charles and the Duke of York) would be uncovered.

One night in that April a flashpoint was reached in Oxford. In a pub in Magpie Lane both students and locals sat drinking, in separate rooms of course. The locals toasted Monmouth so the students toasted York. It was all too much for one student who yelled from the other room asking why the townsmen were so rude. This inflamed one of the students, Mr Taylor, who stood up and ripped off his coat and said he would fight any of them. Taylor was cooled down, but the locals continued to toast Monmouth. Eventually the students thought it would be a better idea if they left.

The bill was paid and the students walked out at 8.45 p.m., but the townies did not leave it there. The students were followed at close distance down the High Street with the locals yelling ‘up Monmouth’. Unfortunately one student innocently going in the opposite direction was clubbed by the townsmen, who cried out ‘kill him, kill him!’. With the mob hot on his heels, the poor student, having been freed, ran for cover in a cutler’s shop. Several attempts were made by the city authorities to remove the ringleaders, but without success. Mr Chartlett, a Deputy Proctor, was a no-nonsense type of man. He spied the mob at Carfax at 10 p.m. and went for the ringleader Will Atkyns. Despite Atkyns’s protest that Chartlett had no warrant, the Deputy Proctor clapped hands on him and hauled him off.

The 300-strong mob supposed that Atkyns would be taken to the Bocardo prison and they besieged the building. But Atkyns had been taken to the Castle gaol instead. While Chartlett tried to make it through the outermost wicket gate of the Castle, the mob were at the Bocardo screaming that they would rescue Atkyns and they would have the Proctor’s blood.

Chartlett had made it through the first and was now at the second wicket gate with Atkyns. By now the mob had realised their mistake and were heading for the Castle. Faced with a locked gate, Chartlett worked frantically to open it, while at the first gate a gentleman from London, a passer-by, kept the mob at bay with his sword. The gentleman may have fought a valiant rearguard action, but over his head projectiles were flying. While working on the lock, Chartlett was being pelted with stones. Possibly it was some consolation that Atkyns was also receiving his fair share of the battering. The mob broke free at the first gate, but Chartlett had managed to unlock the second and succeeded in closing the door on the rampaging masses, having dragged his prisoner inside with him.

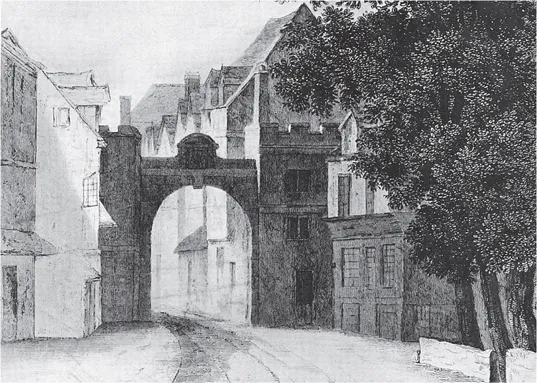

The Bocardo prison, demolished in 1771, abutted the North Gate at the end of Cornmarket Street. The tower of St Michael’s Church rises above the gate. (OCCPA)

The riot continued outside. Some tried to climb in over the walls, others just screamed that they would liberate Atkyns and have the Proctor’s and Vice-Chancellor’s blood to boot. Chartlett was now well and truly stuck inside, but managed to smuggle out a note to the Vice-Chancellor asking for help. Meanwhile, Atkyns was merrily telling his guards that he would see all the University members hanged. So keen was Atkyns that he said he would even see to it personally. For his services he offered to charge the very reasonable rate of 2d for each hanging.

At 1 a.m., in the dead of night, the Vice-Chancellor with men from Jesus College turned up at the Castle and rescued the Proctor, arresting numerous members of the mob as they went. Several men besides Atkyns stood charged with riot at the next Assizes on 4 September 1683, but the jury threw out the charge against them and all the men went free.

ARROGANCE BEFORE A FALL

Dalton, a junior Fellow of All Souls, was returning from a hunting trip in October 1705 when he met a policeman. Such was his pride that he would not lower himself to move for the policeman and tried to force the man aside as they came into contact, but lost out. As the policeman walked away, Dalton, pride dented, turned around and shot the constable in the back. But the policeman was a big, powerful man and ignoring the wound went up to Dalton, took the gun, arrested him and sent Dalton to gaol to await his trial.

PISTOLS AT DAWN

Sir Cholmly Dearing, formerly of New College, and Mr Thornhill were very close friends. Well, they were close until they had a falling out over a ‘matter of honour’. On 17 May 1711, only two weeks after the bust-up, it came to a head. The gentlemen met to duel with dagger and pistol. In this theatrical rendition the first act was also the last. Mr Thornhill was the first to shoot and blew a hole clean through Sir Cholmly. The runner-up in this competition only survived until 3 p.m. that afternoon. Death must have come as a shock for Sir Cholmly and also for his two young sons who survived him. But most of all it would have been a great shock for the woman who had been destined to be his second wife only days later. And this was probably not the final blow-out with friends that Dearing was looking for in the run up to his own wedding day.

DRUMMING UP SUPPORT

Accompanied by a drummer, an officer from the Dragoons was beating up support for volunteers on the Oxford streets one night in August 1715. They were booed and hissed as they went about their business, but carried on until finally they were surrounded. The pair were cornered by a pumped-up mob, which consisted mostly of students. The mob jeered and jostled the soldiers, yelling out ‘down with the Roundheads’. The two men were heavily outnumbered, but forced their way out and pushed on towards the Angel Inn with cries of ‘God save the Duke of Ormond’ echoing in their ears. The good duke at the time was the University’s Chancellor. As the troops neared the doors of the inn, out came a gentleman, sword drawn and ready for combat. He put the fear of God into the officer who, under threat, was made to sheepishly call out ‘down with the Roundheads’. But this token did not buy the soldiers’ freedom, it only served to draw an even larger crowd, who continued the chant. With such large numbers, those who would otherwise not have dared get involved soon joined in. Out stepped a tailor, a well-known Roundhead, to gather evidence against the rioters. He was known locally as ‘My Lord Shaftesbury’ on account that he, like the Earl, was physically deformed. This was a particularly bad move on his part as he was instantly recognised and jumped on; though it did take a little heat away from the battered soldiers.

The would-be informant was driven down the street, buffeted and pushed towards the East Gate, presumably to shove him outside the city and shut the gate behind him. The tailor saw his ‘saviours’ as they rode through the gate and into town. He grabbed the bridle of the first horse, which only served to give the mob a stationary target to flog. The stranger was indignant and asked what the hell was going on. The crowd replied the man was a Roundhead and the rider coolly said, ‘Please, carry on.’ The crowd took great pleasure in this, but presumably the tailor did not.

Despite the fact that attention had been drawn away from them, the Dragoons were still overwhelmed by force and were being pelted with eggs and rocks. The authorities were forced to step in. The crowd was told that if they did not stop they would be reported to the King himself. Ignoring this the mob stoned on – seemingly mobs do rule and strangers are not always kind.

The East Gate, now demolished, lay at one end of the High Street. Outside the city walls Longwall Street leads off to the right behind the trees. (OCCPA)

Two weeks later a group of Dragoons came upon ‘four students of note and distinction’. Not much distinction was made and the only note that would have been heard would have been ‘ow, ow’, as the soldiers gave them a sound beating. It was only when the Vice-Chancellor and others stepped in to rescue them that the students were saved from some rough justice and from being torn to pieces by the miffed Dragoons. It would appear that the score line was one apiece, but the Vice-Chancellor used his power to take the soldiers to task and had all the Dragoons sent away from the city.

Seemingly this was the end of the episode, but it was the Dragoons who would have the last laugh. The final blow was dealt to the University in September 1715 when the Chancellor, the Duke of Ormond, was impeached for high treason and crimes against Parliament. The great man fled for his life to France and Parliament issued a declaration that if he did not surrender himself by the 10th he would be considered guilty and a traitor. It was a bit of a toss-up: he did not return, which left the University perplexed; and they had no Chancellor, although Ormond had not resigned. It was a sticky matter, but it was resolved when a letter was received from Ormond’s brother. The communiqué signified that Ormond finally had resigned, which happily allowed the University to elect his replacement, presumably too happy to notice that its former Chancellor had just been condemned as a traitor.

BAYONET PRACTICE

In June 1716 a scuffle between students and twenty or more soldiers led to the soldiers being beaten and students running away with the soldiers’ swords to Exeter College. The army officers gave orders that soldiers should carry their bayonets fixed and if anybody, townsman or student alike, offered them the least affront, they should stab them.

BIRTHDAY PARTY

On the Prince of Wales’s birthday at the end of October 1716 the lights, as was custom, were displayed in house windows to celebrate the day. Soldiers quartered in the town were told by their major to smash windows where there were no lights. This they happily did, kicking off in the parish of All Saints, smashing windows as they went and throwing burning brands of fire through windows, as well as letting rip with their guns. They abused the Vice-Chancellor and the Mayor, and blew a hole clean through the mace bearer’s hat. The carnage was only stopped when their colonel, lodging at the Angel Inn on the High Street, ordered the soldiers back to their quarters. It was a miracle they had not managed to kill anyone by shot or by fire, least of all that they did not burn the whole city to the ground.

BOG HOUSE RULES

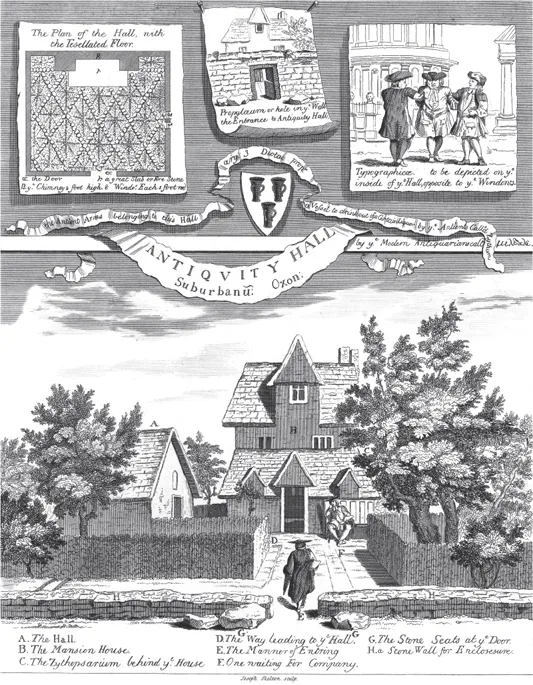

Antiquity Hall, so-called because antiquaries including Thomas Hearne used to meet here, was owned sometime before 1718 by Geoffrey Ammon. He was an ingenious man, well respected for his knowledge of history, geography and heraldry, and was often consulted there by antiquaries as well as students. He was a merry chap, but one night a dispute arose over the bill and Ammon threw a bottle at the offending Exeter student. The bottle cracked the student across his temple. The student staggered out to the bog house where, rather ignominiously, he died. Ammon was charged with murder, but found guilty of manslaughter instead lived to tell the tale for several years to come.

Antiquity Hall in Hythe Bridge Street, 1817. The building was the meeting place for many of the city’s antiquaries, and the site of a fatal dispute in the early eighteenth century. (OCCPA)

WORLD CAVES IN

Cuthberth Ellison of Corpus Christi College, who was described as a sad, dull and heavy preacher, was preaching in February 1719 at St Mary’s. One of the University Proctors, also present, hap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Fighting, Rioting and Duelling

- 2. Theory is Better than Practice

- 3. Country Sportsmen

- 4. Sex, Politics and Religion

- 5. Love’s Labours Lost

- 6. Watery Grave

- 7. Murder, Death and Suicide

- 8. Speaking in Tongues

- 9. If at First You Don’t Succeed, Give Up before You Get Caught

- 10. No Place to Hide

- 11. Students, Fellows and the University

- 12. A Little Knowledge is Dangerous

- 13. Watchmen 4, Drapery Miss 0

- 14. Trials, Punishments and Larking Around

- 15. Body behind the Toilet

- 16. Mother’s Ruin for Father

- 17. How to Win Friends and Influence People

- 18. In the Hunt for Medals

- 19. To Kill a Mocking Rat

- 20. The Town vs Gown Question

- 21. The Gentleman’s Secret Identity

- 22. The Early Days of Mobile Banking

- 23. Working, Robbing and Other Professions

- 24. Policemen’s Punchline

- 25. The Sky’s the Limit

- 26. Fraud, Fire and Oddballs

- 27. To Outsmart a Quack

- 28. Death through Insecurity

- Conclusion

- Bibliography