![]()

Part 1 NATURAL ABILITY AND

SELECTION |

![]()

1

Natural ability

‘Natural ability’ is often discussed when sheep dogs are the topic. It simply means the dog’s natural instincts as they relate to working stock.

Natural ability is the most important aspect of the working dog.

Just as a bitch knows how to chew the umbilical cord and nurse her pups without having to learn, or as a beaver knows how to build a dam, so too the good sheep dog knows how to work stock. It isn’t (or shouldn’t be) a learnt skill, but an inherited one.

So why should this ability be inherited, rather than learnt? There are two reasons.

- The natural worker requires much less training, and becomes a better dog more quickly and easily.

- Only the dog with the right instincts will handle stock well, particularly in difficult situations.

There are simple instincts, and there are complex instincts. For example, a beaver building a dam is an example of a complex instinct, involving various aspects over time. On the other hand most of the sheep dog’s instincts are simple instincts, or reflexes. The dog simply responds to the sheep’s movements or actions in a reflex manner, depending on which instincts it has inherited.

For instance, when a sheep is running away from it, one dog will run straight for the sheep and attempt to grab hold of it. However, the good dog will attempt to get around in front of the sheep to stop it – it will get wider out from the sheep as it heads it off and arc wide around in front of it. This is an instinctive, reflex action.

Yet when many people talk about natural ability, such as the more mechanical-style (and often successful) three-sheep trial handlers, or many UK trial handlers, they often simply mean the right make-up to best enable the dog to be turned into a robot, working completely under command. There is this type of so-called natural ability, and then there is real natural ability.

An example of a somewhat complex instinct in the sheep dog is the extraordinary mustering instinct, which has almost been lost. The ability to muster a big paddock of scattered stock, searching for them, putting some together and starting them on their way, then breaking back out for others and starting them on their way, and so on, until they are all together in a mob, then taking hold of the mob and working it where the dog wills, is instinct at its best. Not many people have seen such natural ability.

Bob Ross receiving the trophy from Queen Elizabeth II, after winning the 1970 National Sheep Dog Trial at Canberra with Yulong Russ. Russ was an exceptional natural worker and influential sire. (Photo reproduced courtesy of The Herald & Weekly Times Pty Ltd

It must be realised that instinct is different from intelligence. You can have a dull dog with good instincts, or a very intelligent dog with poor instincts. The two are more or less separate, and many people confuse them. Just because a dog will muster a paddock on its own does not mean that it is highly intelligent – intelligence is more related to a dog’s ability to learn things quickly. An intelligent dog can be taught a new command or manoeuvre very quickly, whereas the less intelligent dog requires more repetition.

However, the speed at which a dog learns is also affected by other aspects, such as its temperament and instincts. For example, a bold dog may not learn some things as quickly as a timid dog, only because it isn’t as sensitive; yet it may be just as intelligent. The sensitive dog may seem more intelligent in that it is easier to influence, but it may be an illusion. And a dog with natural casting ability may appear to learn to cast more quickly, simply because its instincts guide it.

Instinct and age

A dog’s instincts don’t change with age – they may become evident with age, but they don’t change. That is, some instincts may not be apparent until the dog matures a bit, such as a dog lifting its leg.

Instincts can show at different ages in different dogs, and the age at which they show is inherited. Some dogs’ ‘working instinct’ (the keenness to work stock) surfaces very young, before weaning even. In others it may not surface until 10 months old, or even older in some cases. Personally I like to see it developed fairly strongly by about four months of age, otherwise you can waste too long waiting to see whether a pup is going to be any good or not.

And, despite things that have been said to the contrary, there is no other advantage in either late or early starters. You can have late starters that are over-keen and excitable, and you can have early starters the same. And you can have early or late starters that are calm and sensible. It all depends on the bloodline.

However, once a pup starts, I like to see it start properly. Some pups show some interest, but only in a half-hearted fashion; most pups of this type are ‘weak’ – fear is holding them back. Often they show interest while the sheep are moving, but then, if the sheep stop and look at them, they lose interest. As they gradually gain confidence they begin working more strongly. However, some weak pups can still start strongly, particularly if they have very strong instincts and a lot of ‘eye’; while in contrast a gradual starter may be that way simply because it has only weak instincts.

So, although instinct surfaces at varying ages, once it has surfaced it doesn’t alter. Its expression may alter through gains in confidence or training, but the instinct itself doesn’t alter, and the basic instinct will always surface when the dog is pushed to its limits.

This means that a dog that doesn’t have natural holding ability as a pup will never have real holding ability, even though you may teach it to keep out wide and so on. So don’t make too many excuses for a pup’s faults, because a pup’s faults will become an adult dog’s faults.

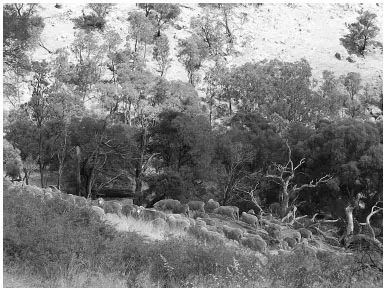

An ideal testing ground to push the best dogs to their limits

This is particularly true in practical work. If a dog is kept solely for trial work, or on small or easy properties, you may be able to hide its faults; however, if you push the dog to its limits in hard practical work they will always surface.

Basic premise for breeding working dogs

The basic premise for breeding sheep dogs is that you should never have to teach a dog how to work sheep. You should only have to teach it a system of commands that allows you to communicate your wishes. Everything else with regard to handling the stock should be inherited natural instinct.

The good dog should keep all the sheep together and never split them unless taught to do so; it should muster a paddock of scattered sheep; cast long distances with very little training; balance and hold and cover wild sheep; it shouldn’t ring sheep on the draw; it should force strongly but cleanly when required, but not otherwise, and so on. This is the real sheep dog – the natural sheep dog.

You can breed for just about anything you set your heart on, provided that you understand how to go about it. Nearly every aspect of the working dog’s behaviour is, or can be, inherited. For example, the place where the dog bites (if and when and how it does); the way it sits when riding on a motorbike; how many steps it takes before stopping when told; and so on. These things are all inherited (they can be modified by training) but you can breed for anything you like.

The trick is in knowing what you want, and knowing what makes a top dog.

Instinct is the most important factor of the working dog, because it determines how well the dog will handle stock, particularly in difficult situations or if left to work on its own resources, and how easy it will be to control and to work, and how much it will think about what it is doing.

Strength of instinct

A dog’s instincts can vary from weak to very strong. For example, some dogs’ heading instinct (particularly many three-sheep collies) is excessively strong and requires a lot of control to harness it, whereas a dog whose instinct is not so strong will be easier to control.

However, some breeders, in trying to breed easily controllable dogs (which is good, depending on how it is achieved), simply breed dogs with fairly weak instincts, that is, lacking real keenness. But, even though such dogs are easier to handle, they tend to lack much ‘heart’ (the desire to keep working in the face of just about any hardship).

It is possible, though, to breed controllable dogs with strong instincts and great heart. The clue lies in breeding calm dogs with the right instincts, as explained later.

The working traits

In the following chapters I have provided a reasonably comprehensive breakdown and analysis of the instincts and qualities that combine to make the working dog.

A knowledge of them allows a more accurate assessment of a dog’s abilities, and hence more accurate selection for breeding.

If you are ever going to breed top dogs, then, rather than just thinking that a dog is ‘a good dog’, you must be able to break its work down into individual traits, so you know exactly why it is a good dog.

A clear understanding of the make-up of the good dog will help anyone to breed better dogs. Only then will you be able to develop a clear goal in your mind of exactly what a good dog is, and what you are trying to breed and select for, so that you aren’t fighting against yourself (which can easily happen).

One vital point is that it is difficult to assess many of these characteristics when the dog is seen working quiet stock in a small area, or under tight control. You must see it tested in difficult situations, and left to work on its own resources.

For example, it is difficult to know how much ‘mob cover’ some dogs have, when they are working a few quiet sheep that plod about and stick together. Only when you see them handling a dozen wild, shorn wethers or similar, which are running and splitting and carrying on out in a paddock, can you get a good idea.

Always make a point of testing a dog beyond its limits. Only by seeing it pushed beyond its limits can you see its limitations.

The modern trend to work dog trials on quietened sheep is deplorable (and this includes not only three-sheep trials but also trials such as the national Kelpie utility trial). Not only do these trials greatly reduce the challenge and skill involved, but also they don’t provide the breeder with a sufficient insight into the dog’s natural abilities. Many dogs look good on quiet sheep, if they are well trained. But only the high quality natural dog will look good on wild sheep (or wild cattle, for that matter). Sheep dog trial handlers with the better natural dogs sometimes comment that the only time they can get among the winners is when wild sheep are worked, because with quiet sheep the more mechanical dogs can score highly.

Pat Murphy’s high quality, big casting, all-round Kelpie dog Paddy’s Shadow (Karrawarra Boogles × Paddy’s Loo). (Photo courtesy Pat Murphy.)

People often reminisce about the ‘old-time Kelpie’ and regret that such dogs are rarely seen today. But there is nothing mysterious about those old-time dogs; they were simply the product of experienced and knowledgeable stockmen selecting for a certain type of practical dog, without any thought of breeding to win trials. The same can be said about the ‘old-time’ Border Collie.

The reason those dogs aren’t common now ...