- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

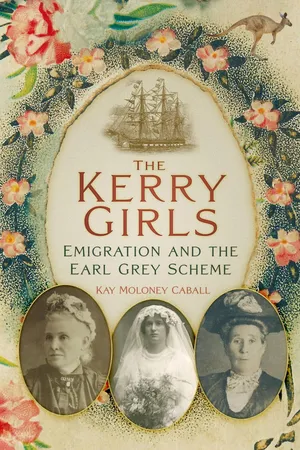

As part of the controversial Earl Grey Scheme, this is the true story of the Kerry girls who were shipped to Australia from the four Kerry workhouses of Dingle, Kenmare, Killarney and Listowel in 1849 and 1850.

Leaving behind scenes of destitution and misery, the girls, some of whom spoke only Irish, set off to the other side of the world without any idea of what lay ahead. This book tells of their 'selection' and their transportation to New South Wales and Adelaide, their subsequent apprenticeship, and finally of their marriages and attempts to rebuild a life far from home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Kerry Girls by Kay Moloney Caball in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BACKGROUND TO THE FAMINE IN KERRY

KING WROTE IN his History of Kerry, ‘During the first half of the nineteenth century distress was the constant condition of the people of Kerry’. The spectre of famine was never far off. In 1821, out of a county population of 230,000, 170,000 were reported to be destitute of the means of subsistence’.1 It is not surprising then that this endemic poverty, together with the rapid growth in the population and the misguided administration of the British Government over its Irish citizens, lead to the disastrous famine of 1845–1852, a human tragedy of staggering proportions.

During that period hundreds of thousands died of hunger and disease. Hundreds of thousands of Irish emigrated to England, Australia and the Americas. By autumn of 1845 when the Great Famine struck, there were more than 8 million people living on the island of Ireland. The population of Kerry had risen from 216,185 in 1821 to 293,256 in 1841, an alarming 77,071 increase, one of the highest rises in a countrywide population that was escalating rapidly. However, by 1851, after six years of famine resulting in death and emigration, the combined population of the eight baronies that comprised the County of Kerry had dropped to 238,256 in 1851 – a decrease of 55,624 persons in ten years.2

While we cannot say with certainty how many people died in Kerry or how many emigrated during the famine period, we know that 117 girls were part of the exodus. They emigrated through the Earl Grey Scheme and came from four of the six Unions in Kerry – Dingle, Kenmare, Killarney and Listowel in 1849 and 1850.

While each of these Union baronies from which the Kerry ‘orphans’ originated, had its own individual problems and challenges that were responsible for the high death rates and emigration, there were a number of problems common to all geographic areas of the county.

What caused the Great Famine and contributed to its disastrous results? While the loss of the potato crop, which was the main diet of the poor, was the proximate cause, there were a number of other reasons: widespread poverty among the majority, unemployment, overpopulation and an unsatisfactory system of landownership. A Royal Commission set up by the British Government under the Earl of Devon reported in 1845:

It would be impossible adequately to describe the privations which they [Irish labourer and his family] habitually and silently endure … in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water … their cabins are seldom a protection against the weather … a bed or a blanket is a rare luxury.3

In Ireland at this time, the daily intake of a ‘third or so of the population was mainly reliant on the potato … 4-5 kilos daily per adult male equivalent for most of the year’4 This may seem now like an enormous amount of potatoes for anyone to eat in one day but washed down with buttermilk it was in fact a very healthy diet.

The nutritional content of the potato and widespread access to heating fuel in the form of turf, eased somewhat the poverty of Ireland’s three million ‘potato people’, who were healthier and lived longer than the poor in other parts of Europe at the time.5

Arthur Young noted in 1779 that the potato was largely responsible for the healthiness of the Irish: ‘when I see their well formed bodies … their men athletic and their women beautiful, I know not how to believe them subsisting on an unwholesome food.’6 John Pierse, in his book Teampall Bán, quotes his ancestor Dr John Church: ‘I think they are healthy; I see them sometimes come out in crowds out of the cabins, sometimes perfectly naked, and we have been astonished to see how healthy they are.’7

While the loss of the potato crop may have been the immediate cause, too many people on too little land without fixity of tenure contributed to the disaster in no small way.

The colonisation of Ireland began with the Normans’ arrival in 1171, but it was in the reigns of Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Oliver Cromwell and William of Orange that the main confiscation of Irish land took place. Irish lands were granted by the Crown to English or Scottish planters. These new planters, of English stock with a Protestant identity then became powerful landlords over vast tracts of land.

In 1695 harsh Penal Laws were introduced. Irish Catholics who had been dispossessed of their own land were then prohibited from buying land, bringing their children up as Catholics, from entering the forces or the professions. Neither could Catholics, Jews, Protestant Dissenters (non-Anglicans) and Quakers run for elected office or own property (such as horses) valued at more than £5. So, instead of owning land, most rented small plots from absentee British landlords. While tenancy can be a very efficient and fair way to use land, this was not the case in Ireland.

This system of landownership was one of the major causes of poverty. It is estimated that by the time of the Famine, 70–75 per cent of all tenants held land ‘at will’8 and leases were generally short or at most let for one life and twenty-one years, instead of the former system of three lives, with explicit clauses against subletting which in the main were not observed by the tenants. There was little or no security of tenure. By law, any improvements made by the tenant, such as draining the land, building fences or even erecting a stone house, became the property of the landlord. Thus there was never any incentive to upgrade their living conditions. The landlord could also increase the rent if the tenant’s ‘improvements’ warranted it. Tenants could be evicted between leases if the landlord or agent could make more money out of the land themselves, or get a higher rent from another tenant. These landowners, unlike the situation in England, had no link to their tenants save an economic one. They had acquired their estates during the plantations and confiscations over the previous 200 years. One such acquisition was in 1666, when the Provost, Fellows and Scholars of Trinity College, Dublin, were granted 54,479 acres of land in Kerry. By the early 1850s, most of this land was sublet to agents who in turn sublet it to tenants. At the eve of the Famine, Trinity College owned 6.4 per cent of the county.9

While the majority of Kerry landlords were absentees, they were represented in the area by these agents or middlemen. In a lot of cases, the latter were more feared than the actual landowner. They managed the estates of the absentees, set the rents, let and sublet the land. They were the ones who had the power to call in the bailiffs, evict tenants and put them on the side of the road.

The tenants were also separated from their landlords by culture, religion, language and a great sense of dispossession. Many of these Catholic tenants were now paying rent to families who had driven their ancestors out of the land they had previously owned for generations. On their part, the landlords did not have a great sense of security and did not relish living among what they saw as a disgruntled, unreliable peasantry. As a result, the major landowners lived elsewhere, some in other parts of Ireland but mostly in England. Rents collected to fund their extravagant lifestyles on their English estates were the main objective of this landowning class.

An addition to the landownership problems was the practice of subdivision. By 1841, the growth in population, resulting from marriage at a younger age, meant that land distributed among a number of sons, over a couple of generations, led to each holding becoming smaller and smaller until it was barely enough to support a family.

Social and living conditions in Kerry in the first half of the nineteenth century were diverse and wide ranging. At the top of the social ladder you had the aforementioned landlords, living outside the county, where they looked after their other estates, their commissions in the (British) army and/or their seats in Parliament. Next you had a slowly emerging merchant class in the towns, who lived in substantial houses with servants and a prosperous lifestyle. These were mostly Protestant, but since the Repeal of the Penal Laws in 1782, a Catholic minority of business people was emerging. In the country you had a small number of ‘strong farmers’, those who held 30 acres or more. Survivors of the famine, who were interviewed in the 1920s by Bryan MacMahon all agreed that ‘comfortable’ farmers were not in serious distress during these times.10

The average tenant farmers were those with between 5 and 30 acres. On this acreage they were living at subsistence level. Then you had the cottiers and labourers, who were the most numerous, and it was this section of the community who were wiped out during the Famine. A cottier or labourer might have half an acre, where he would grow potatoes and build a cabin. He would pay the farmer for the land, usually about £5 (1800s) or, more often, with his labour. This plot of ground was an essential need; without it he starved. These cottiers and labourers usually kept a pig and hens and most lived in one-roomed mud houses without windows or chimney. The 1841 Census classification distinguished between four types of houses. Fourth-class houses were defined as ‘all mud cabins having only one room’.11

Imagine four walls of dried mud (which the rain, as it falls, easily restores to its primitive condition) having for its roof a little straw or some sods, for its chimney a hole cut in the roof, or very frequently the door through which alone the smoke finds an issue. A single apartment contains father, mother, children and sometimes a grandfather and a grandmother; there is no furniture in the wretched hovel; a single bed of straw serves the entire family.12

These labourers and cottiers in Kerry at this time had a very low standard of living. They were poorly clothed and very few had shoes. A detailed enquiry into rural poverty reported in 1836 that an agricultural labourer could, on average, count on 134 days of paid employment in a year.

The cottier or labourer would have married young, men at 18 or 19 and girls at 16 or 17, and had a large family. The labourer’s children, mos...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Background to the Famine in Kerry

- 2 Life in the Workhouse

- 3 Circumstances in Australia

- 4 Workhouse Decisions

- 5 Background to the Girls

- 6 Voyage and Arrival

- 7 Working Life and Marriage in Australia

- 8 Pawns in an Imperial Struggle?

- Conclusion: An Opportunity or a Tragedy?

- Appendix: Orphan Database

- Notes

- Bibliography