- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Story of Cardiff

About this book

Cardiff has been on the frontline of Anglo-Welsh history, a place where the hammer blow of the past has periodically fallen hard. To really understand the character of a city you have to be aware of its scars: listen to the suffragettes, soldiers, slaves, martyrs, rebels, pirates and priests, and in the testimonies of each and every one you will find a number of prescient truths about Cardiff. Nick Shepley has an eye for a telling anecdote and this, together with his lively and authoritative research, makes The Story of Cardiff appealing to anyone who is seeking to find out more about this fascinating city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Story of Cardiff by Nick Shepley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ten

THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY

King Edward VII granted Cardiff city status on 28 October 1905. The mayor became a lord mayor and the city acquired a Roman Catholic cathedral in 1916. This growth in civic importance was matched by industrial progress and in 1913 the docks reached their zenith with 107 million tons of coal exported through them.

The tensions that industrialisation built up in Cardiff in the nineteenth century, coupled with the stresses on working people that the city’s introduction to the global economy and labour market had brought about, exploded into violence in the period of the ‘Great Unrest’ between 1908 and 1914, when there was industrial strife across the country and a working-class militancy that has never been seen since. A century of rapid industrial growth and the formation of an educated and politicised working class was hardly likely to be without consequence. In Cardiff the result was racial violence against and intimidation of the Chinese community in 1911, when sailors and dockworkers went on strike in support of the Liverpool Seamen and Dockers, who had been part of a general transport strike in Merseyside. In a bid to keep the docks open and coal moving to ports across the world, Chinese sailors and dockworkers were employed, triggering a frenzy of attacks against the strike-breakers and against the Chinese community that had lived in Canton for much of the nineteenth century. This was exceedingly rare in Cardiff’s history. There was ethnic violence triggered by economic desperation and communities pitted against one another by shipping magnates desperate to end the dispute. The level of violence and disorder that summer was sufficient to urge Home Secretary Winston Churchill to deploy 500 soldiers to the city to ensure the return of law and order. This was not the last time that racial violence born of economic struggle would grip the city. Following the First World War there was another outburst, again focused on the docks but this time attacking the black community.

The Welsh National War Memorial is situated in Cathays Park, Cardiff. Built in 1928, it was designed by Sir Ninian Comper.

It might well be that the level of success enjoyed by Chinese small businessmen provoked a deep-seated resentment. By 1910 there were twenty-two Chinese laundries employing fifty-five Chinese, seven ordinary houses occupied by Chinese, and four Chinese licensed boarding houses accommodating ninety-eight seamen. Only 2 per cent of seamen signing on were Chinese, although union officials constantly called for support against the threat of job losses, and there was an unspoken racism that stemmed from an ignorance about Chinese culture. There was a fear that the industrious and hard-working Chinese would drive down wages or be used as scab labour. This competition between ethnic and social groups is now established practice in our post-industrial world, as jobs are routinely outsourced to the Third World.

The material concerns of the strikers were clouded with imaginary fears and suspicions about the Chinese. For example there were raids on Chinese lodging houses, where it was alleged that white girls were being held against their will. The obsession that chaste white women were being corrupted by crafty foreigners is hardly unique in the annals of bigotry but it gives us an insight into the unspoken fears and anxieties of workers who felt their status threatened.65

The attack on the Chinese in 1911 shows how ethnically diverse Cardiff had become, and how far as a community the city had to go before it was able to resolve the ethnic tensions and differences that were thrown up by the new global economy it had joined.

The Temple of Peace

In Cathays Park stand two physical embodiments of the unexpected catastrophe that engulfed Europe, Britain and every city, town, village and hamlet in the British Isles. One is the War Memorial, unveiled in 1928, and the other is the Temple of Peace, created by the League of Nations during the 1930s, which was dedicated to preventing a repeat of the bloodshed of the First World War. The Welsh National Temple of Peace and Health was opened in 1938 when the last desperate attempts at establishing ‘peace in our time’ were failing. It was opened twenty years and a fortnight after the guns fell silent on the Western Front and still stands today, a beautiful but sombre fusion of neo-Classical and modernist architecture. The creator of the temple, Baron David Davies, intended it to be a lasting tribute to the enormous sacrifice of men around the world who had fought and died in the First World War. The Liberal peer and pacifist was part of a generation of activists who worked during the 1930s to further the cause of the League of Nations. He was interested in the possibility of using psychoanalysis to deal with mankind’s inherently aggressive and destructive nature, though when the projected timescale for this turned out to be a couple of centuries (known as ‘the Morbid Age’), Davies devoted his energies to other more practical issues.

The Falklands War Memorial, dedicated to the Welsh Guards killed at Bluff Cove during the conflict on 8 June 1982.

The building initially housed the Welsh National Council for the League of Nations Union and the King Edward VII National Memorial Association, dedicated to alleviating tuberculosis. Lord Davies continued to campaign throughout the Second World War for an end to war and the establishment of a supreme international body that would eliminate the need for it and make it illegal. He died in 1944, just ten days after D-Day, his dreams of a peaceful world in tatters, with only the temple standing as a lasting testament to his works. It is tempting to look upon the notion of outlawing war as naïve, but we should remember that Lord Davies represented an enormous mass movement against war and in favour of the League of Nations throughout the 1930s, which only began to lose support after the Czech crisis, when war with Hitler appeared to be inevitable.

The Temple of Peace also houses the Welsh National War Memorial, which dates from 1928. It was first proposed by the Western Mail in 1919, and the newspaper started a fund to establish it. It has been suggested that the location of the memorial in Cardiff was controversial, perhaps because the city was seen as unrepresentative of Wales as a whole. In May 1919 the Cardiff Times wrote that Councillor H.M. Thompson had misgivings about establishing a national memorial in Cardiff: ‘He did not think it would be possible to secure agreement with North Wales for a National Memorial at Cardiff, as most likely they would prefer memorials to their fallen in their own localities. What was wanted was a great memorial for Cardiff itself and not for the whole of Wales.’66

Contemporary accounts suggest that the response from across Wales was distinctly lukewarm: of those local authorities contacted, only sixty-three responded and of those only twenty-one responded favourably. Cardiff was felt to be too far away – in 1919 visiting it would have been beyond the means of many people in Wales, and most rural communities established their own small civic memorials. Those authorities which sympathised, such as Pembroke, did not have the finances to contribute to the project. Hostility towards Cardiff as a predominantly English-speaking city was a motivating factor in some instances, especially in North Wales. A particularly sour editorial in the North Wales Chronicle sheds light on how the city was viewed:

We offer our condolences to Cardiff. The cosmopolitan self-appointed ‘metropolis’ of Wales has experienced yet another and very serious rebuff. Public authorities in Wales have actually had the temerity to refuse to pander to Cardiff’s ambitions, and declined to fund the funds for erecting an imposing National War Memorial in Cardiff, intended partly for the commemoration of Welsh heroes in the war and largely for the glorification of Cardiff in Wales. Some 200 public bodies in Wales were circularised by the Lord Mayor of Cardiff and invited to assist Cardiff in erecting a National Memorial in a town which prides itself ten times more on its cosmopolitan than upon its national character. Only one authority out of every ten so circularised even expressed willingness to send representatives to another Cardiff ‘national’ conference to discuss the proposal. In a huff, the Cardiff City Council now declares it can do without Wales, and will forthwith erect its own Peace Memorial.67

The Welsh National War Memorial. The memorial was inspired by Roman architecture in North Africa dating back to the reign of Emperor Hadrian and is a Grade II listed structure.

The Inner frieze (below) reads: ‘Remember here is peace those who in tumult of war, by sea, on land, in air, for us and for victory endureth unto death.’

The Inscription reads: ‘FEIBION CYMRU A RODDES EU BYWYDDROS EI GWLAD YN RHYFEL MCMXVIII’: TO THE SONS OF WALES WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES FOR THEIR COUNTRY IN THE WAR 1918.

There was considerable controversy when it was built as North Walian communities who had lost men to the war felt that Cardiff was not representative of Wales and therefore not the place for a national memorial.

Glamorgan Home Guard annual parade at Cardiff Castle. During the war, Cardiff’s men who were too young or old to fight overseas joined the Home Guard.

The requisite funds were raised, with the majority of the money being raised in Cardiff and even a few donations from overseas. When it was unveiled the Peace Memorial was the largest memorial in Wales. The recriminations and bitterness as the memorial was commissioned and built identifies the disconnect between rural and North Wales and Cardiff (it had sprung up as a metropolis in a generation and lacked legitimacy in the eyes of many Welshmen) and the unspoken national trauma that would hang over Wales for the next two decades. All this was a far cry from the scenes of jubilation and enthusiasm that greeted the announcement of war in Cardiff in 1914.

The First World War

David Lloyd George, whose career went from strength to strength during the war, leaping from armaments minister in 1914 to prime minister in 1916, oversaw the creation of the 38th Welsh Division, a body of men that raised several battalions from Cardiff. Welsh nonconformism, nationalism and socialism all had a strongly pacifist sentiment, which meant that many battalions were staffed by Welsh officers with the rank and file from England. However, 1,000 men were recruited in the winter of 1914 for the 16th Cardiff City Battalion, even though initial euphoria had been replaced by a more sombre and solemn attitude to volunteering. Some travelled from other parts of South Wales, but for the most part these men were Cardiffians. Recruiting drives at football matches, rugby games, places of work and music halls were all used, and open-air concerts by military bands saw men joining up. In all it took eight weeks to get the full quota.

An indication of the success of recruiting at sporting events was the number of Welsh international rugby players in the 16th, including Capt. John L. Williams, Lt H. Bert Winfield and Lt J.M. Clem Lewis. Club vice-captain Maj. Fred Smith was second-in-command of the battalion and became its commanding officer when Lt-Col. Gaskell was killed in 1916.

The battalion trained in Britain for a year, and finally arrived in northern France in December 1915 and saw their first action in the Givenchy-Festubert-Laventie area (where Lt-Col. Gaskell was killed). Their losses for May 1916 were comparatively light at only fifty men. In contrast, Cardiff paid an extremely high price on the Somme, with at least half the 16th Battalion being killed or wounded at the Battle of Mametz Wood. On the site of the battle today a memorial to the 38th Division stands, a red dragon grasping barbed wire. It is a small reminder of the unimaginable slaughter that the Welsh Division and its Cardiff contingent faced over the five days between 7 and 12 July.

One of the other Cardiff battalions was the 8th Pioneers, who took part in the Dardanelles Campaign. They landed as part of Winston Churchill’s disastrous strategic blunder on 5 August 1915 and spent four murderous months under a hail of Turkish gunfire, contending with artillery, disease and lack of supplies before being evacuated in December. The men had been ill-equipped, had not been trained for the kind of fighting they were faced with and orders were vague. Along with the rest of the 53rd Welsh Division, they were used by the same generals who had wasted the lives of the Australian and New Zealand troops who had come before them. Following their evacuation from Gallipoli to Egypt, the battalion took part in the 1916 invasion of Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and the capture of Baghdad.

Cardiffians served in every branch of the armed forces, and the city’s maritime importance led to many young men enrolling in the Royal Navy. The fact that over 1,000 black Cardiffians from Butetown and Cardiff’s Docks fought and died in Jellicoe’s navy has been shamefully under-reported in official histories.

Of the 1,356 Victoria Crosses issued, the Welsh have featured extensively, and Cardiffians in particular have a strong presence in the list of those decorated. Here are just two of the soldiers from Cardiff who were honoured with the Victoria Cross:

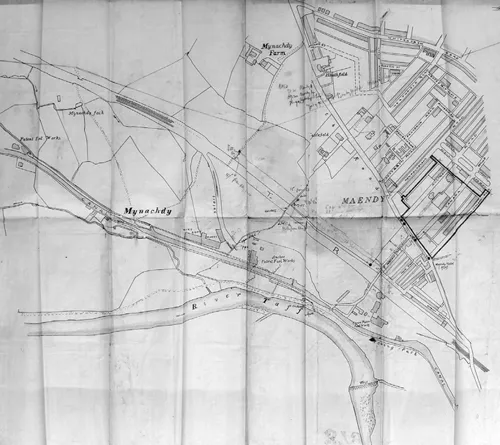

Plans and sections of streets in Maindy, an architect’s design of the streets of the district. Maindy was redeveloped in the late nineteenth century from land provided by the Marquis of Bute.

Frederick Barter of Daniel Street, Cathays, and later Harold Street, Roath, was born in January 1891, one of four children. He was educated at Crwys Road Board School before working for the GWR as a porter. Barter went on to become one of the most highly decorated soldiers in the First World War, all the more amazing as he was turned down for regular service before the war because his chest measurement did not meet minimum requirements. Forced to give up on his ambition to join the regular army with his brother John, Barter joined the militia battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, enrolling at Maindy Barracks on Whitchurch Road in 1908. He was quickly promoted from private to lance-corporal in 1909, corporal in 1910 and sergeant in 1911. Military reforms pushed through in 1908 in response to the sabre-rattling of Kaiser Wilhelm II disbanded the militia battalions, and Barter was incorporated into the special reserves of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. At the outbreak of war he was sent from Cardiff to Wrexham, where he was promoted to the rank of company sergeant major. By this time the 1st Battalion of the Fusiliers had already seen their first action in France, and one of those reported missing was Private John Barter.

The Special Reserve Battalion was quickly sent to Belgium to relieve the mauled 1st Battalion, and spent a long winter defending the frontline against further German attack and conducting raids into German trenches. In the spring the 7th Division, of which the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were part, moved south, Barter and his men being positio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- One Early Settlement

- Two Roman Development

- Three The Middle Ages

- Four The Tudor Age

- Five The Seventeenth Century and the Civil War

- Six The Eighteenth Century

- Seven The Nineteenth Century

- Eight The Expanding City

- Nine The Bute Family

- Ten The Early Twentieth Century

- Eleven The Post-War City

- Epilogue The View From St Peter’s Street

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Copyright