- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

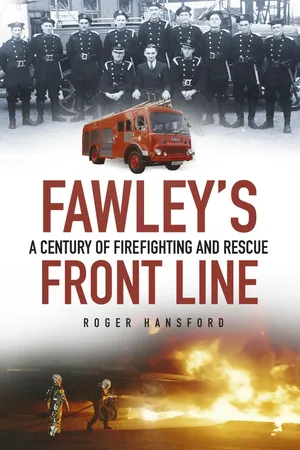

Home to the UK's largest refinery, Fawley is among the most at-risk parts of the country for petrochemical fires. Its fire service is vital to the area's infrastructure and its firefighters must always be prepared. For the first time, the story of this fire station and of the Waterside's private and military fire brigades is told. From establishment in the early twentieth century, through the development of the fire engine and firefighting techniques, to combating modern-day terrorist threats, Fawley's firefighters have witnessed it all. This book looks at how the station and its crew, now reduced from full- to part-time staffing, have evolved in the face of new dangers and challenges.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fawley's Front Line by Roger Hansford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

CADLAND ESTATE AND THE EARLY FIRE BRIGADES

At the start of the twentieth century, much of the parish of Fawley was rural in character, and the area consisted of villages, farms, lanes, farmland and woodlands. Significant buildings were the Norman church at Fawley and the Tudor stone castle on Calshot Spit. By this time the Drummond family was well established at the Manor of Cadland, having extended the house originally designed by Henry Holland and set in ‘Capability’ Brown parkland. The records of a fire at the estate farm in the late nineteenth century give a glimpse of the practice of firefighting in the parish at this time. My research on the fire is sourced from two accounts of the event, which I refer to as ‘Report 1’ and ‘Report 2’, both included as cuttings in the Drummond family’s scrapbook dated 1894. It has been difficult to date the incident precisely, but it could have been the fire at ‘Cadlands Farm, Cadlands’ attended by Southampton Fire Brigade on Sunday 1 March 1885, as documented in their records (SC/F 1/1).

Report 1 describes a ‘destructive fire at Cadlands Home Farm’. This was ‘of a very extensive character’ and destroyed five ricks of hay, six of barley, four of wheat, one of barley straw and one of ferns, later spreading to the granary and cart house, which almost completely burnt down. The initial alarm was raised at 8 p.m. on the Saturday by a Mrs Sarah Fry, steward to Edgar Atheling Drummond and servant to the farmer, Mr Hogg. At this, ‘the farm servants and others quickly mustered, and there being a plentiful water supply, the fire was soon extinguished’. Although a watch was kept on the yard, fire broke out again at 1.30 p.m. on the Sunday. This was attributed to brisk winds fanning embers from the previous day’s fire, which had been spread out in the open close to other ricks. Report 2 stated that in total some eighteen ricks were on fire within ten minutes of the alarm being raised in the village by one of the farm boys.

Report 1 details which fire brigades responded, and how they were called. Two engines were sent from nearby estates, one by Count Batthyhany of Eaglehurst Castle and another by Lord Henry Scott of Beaulieu. The naval vessel HMS Zealous was anchored off Netley, and dispatched two engines ‘manned by marines and sailors, and taken in boats up Cadlands Creek, to the scene of the fire’. These engines, when on land, were probably drawn by horses, with pumps operated manually or using steam. Report 1 suggests the engines were mobilised when the fire was sighted: ‘The conflagration was of course very great, lighting up the whole country round.’ More sophisticated methods of despatch were also in use, however, as this report informs us that a telegram was sent to Superintendent Gardner of Southampton Fire Brigade (SFB). Despite a slight difference in spelling, there was a Mr W.H. Gardiner in charge of SFB from 1876 until the mid-1880s, the term ‘Superintendent’ being used instead of Chief Fire Officer at that time. The officer and his personnel took the shortest route to the fire by catching the Hythe Ferry across Southampton Water. Meanwhile, their engine was sent around by road through Redbridge and Totton, but returned to base after meeting Mr Hogg’s messenger in Totton, who stated the fire was too seriously advanced for the engine to be of use. This left the Southampton firemen to assist the crew from Beaulieu, whose engine was the first to arrive. Report 2 said it was ‘thought necessary to telegraph for the Sappers and Miners’, and that the Sappers had arrived at Hythe before receipt of a second telegraph saying they were no longer needed. This may refer to the Southampton engine described in Report 1.

Report 1 gives an idea of the firefighting methods employed at the scene. The fire had spread too rapidly for those present to remove the carts from the cart house before it was engulfed. However, they did remove cattle from the cattle house and sprayed water on the farmhouse and other buildings to prevent them from igniting. Several water sources were available, all of which were utilised. There was a large tank of water 300–400m from the rick yard, and Report 1 states: ‘Two lines [of people] were formed from the yard to the tank, the one side passing empty buckets down from hand to hand, and returning full buckets of water in the same way on the other sides, and thus some of the engines were kept supplied with water.’

In this task, the Southampton and Beaulieu teams ‘did exceedingly good work, the men behaving themselves admirably’, and they were supported by many volunteers. Among the volunteers were important local figures including Mr Hogg, Mr Drummond, Mr Jenkinson, Revd Unwin, Dr Stephenson and Mr Perkins, and the same report states, ‘other gentlemen came, each lending a hand at the pumps or hose’. Meanwhile, Count Batthyhany directed the sailors and others in showering water onto the burning ricks from the farm pond, where one of the Zealous engines was working. Twenty men from HMS Zealous worked through the night with water from a tank in the roof of the corn mill, managing to save the corn and a threshing machine. The first team worked until midnight, when they were relieved by several other detachments from the ship, each led by an officer. This coheres with the Southampton Fire Brigade record, which mentions the attendance of private and manual engines not of SFB, and says the Cadland blaze was extinguished by ‘Firemen and Strangers’.

Despite the efforts of all involved, the impact of the fire was huge, doing damage estimated to cost £15,000, and ruining a good harvest along with the farm buildings. Smoke continued to issue from a hayrick at the scene on Monday, leading local people to believe the fire was still burning then, and there were unfounded rumours in Southampton and Beaulieu that Cadland House itself had been on fire, and even that fires had occurred simultaneously at Broadlands and Netley.

A tragic fire at Cadland Farm on 11 May 1923 was triggered by a boiler explosion and caused £5,000 worth of damage. Southampton Fire Brigade’s motor pump No. 3 attended the call, which had been raised by Leycester Meyer of Fawley. Alfred James Eldridge, aged 29, was killed in the incident along with his horse and three calves. (Waterside Heritage)

Enquiries were made into the origin of the blaze, and the police officers Superintendent Troke and Sergeant Fox concluded that the cause of the initial fire on the Saturday was accidental. Report 2 suggested spontaneous combustion as a possible cause of the fire on Saturday, and questioned whether ‘the crime of incendiarism’ had played a part in the fire’s rapid spread on Sunday. This was thought unlikely given that watchmen had been on guard all morning, and also that Mr Drummond was well-respected in the area. He was not a ‘hard landlord’ but ‘a most affable and kind gentleman, taking delight in and doing his utmost to promote everything that is for the improvement of the estate’. The author was ‘not afraid to assert’ that he was ‘more regarded and respected by all classes’ than any other landlord in the country, and could therefore ‘scout the idea with scorn that anyone of the parish of Fawley could have been guilty of such a dastardly outrage’. A final suggestion was that a ‘fanatic’ of the ‘destestable Trades’ Unions’ may have started the fire, but no such guilty party could be found. Put in context of the scientific approaches to fire investigation used in modern times, it is amusing that the accidental verdict was based largely on the character of the property owner. I suggest the failure to keep burnt embers away from fresh crops on the Saturday, and the rejection of the Southampton engine on the Sunday, leaving its crew unequipped and depriving the incident of an extra pump, were significant errors. Interestingly, the nineteenth-century reports do not question the allegiances or competence of those left to watch the yard before the main outbreak on Sunday morning!

The accounts of the Cadland Farm fire in Reports 1 and 2 are significant because they raise issues that have been important for firefighting in the parish – and in this location – over the last century. The reports evoke pictures of a rural landscape where farming was paramount, and rural firefighting has been commonplace in the surrounding area ever since. After development as an industrial site, the land at Cadland often saw fires and incidents where different fire brigades would respond and work together. The military are mentioned in the Drummond reports and they were involved with firefighting and rescue in the wider vicinity at different times; for example Southampton Fire Brigade recorded assistance from soldiers and sailors at a fire in Bourne Hill Cottage, Fawley, on 10 September 1916. In the 1880s many people from the community were prepared to help at Cadland on a voluntary basis, showing a willingness to serve in the face of danger which has not disappeared in the present day. Some of the firefighting techniques used in the farmyard, such as passing buckets down a line of people, differed little from those used since ancient times and employed, for example, at the Great Fire of London in 1666. Such techniques continued to be used into the early 1900s. The methods used to prevent fire spreading anticipated modern techniques, but the inefficiency of communication between fire teams contrasts strongly with the present. Finally, although four engines were called to a fire within the parish, all of them came from stations outside the boundary and none of them were from Fawley.

2

MODERNISATION AND WAR: THE BEGINNINGS OF ORGANISED FIREFIGHTING IN FAWLEY

The first significant signs of change in Fawley occurred in 1920 when the Atlantic, Gulf and West Indies Oil Company (AGWI ) started building a small refinery for bitumen and bunker fuels on land from the Cadland Estate. On 19 July 1921, SFB recorded attending a fire, with Engine No. 3, which had broken out in 500 out of the 1,200 sleepers piled beside the Totton railway line that were ‘to be used for the new Fawley line’ (SC/F1/1). This call-out heralded the arrival of the railway on the Waterside, meaning the area would no longer be isolated from development.

A fire brigade began in Fawley’s neighbouring parish of Hythe in 1919, moving to a purpose-built fire station in New Road in 1927. Pam Whittington’s Hythe Fire Brigade: A Local History (1998) tells the story of this brigade, including incidents they responded to within the Fawley area. In contrast, it would be another half-century before the parish of Fawley had its own purpose-built and permanent local authority fire station. Yet the area had a successful volunteer fire brigade before the legal requirement to provide a Fire Service came in the late 1930s. This chapter covers developments underlining Fawley’s need for a local authority fire station and describes the measures taken in the meantime to save life and property from fire. From the 1920s to the 1960s the degree of petrochemical risk was to increase unrecognisably and special arrangements were needed for the threat of armed assault and invasion by Nazi Germany. However, it was not until the 1970s that the new fire station was built.

The Fawley Volunteer Fire Brigade in the 1930s

During the first decades of the twentieth century there was no fire brigade in the area. No legislation required such provision and no piped water supply was available. The population relied on pumps and wells for domestic purposes and the authorities jostled to avoid responsibility. The minutes of the Fawley Parish Council, held at the Hampshire Record Office in Winchester (Shelfmark 25M60/PX1), show how the need to improve firefighting capacity was recognised in the parish as early as 1927, but it was initially difficult to obtain necessary backing from the New Forest Rural District Council (RDC). The entry for a meeting held on 21 March 1927, at 7 p.m. in the Public Hall, reads:

Fire Hydrants

Mr. G. Musselwhite brought forward the question of Fire Hydrants, stating that in view of the recent disastrous fire at Copthorne, and difficulty of obtaining supplies of water in case of fire, he considered that it was advisable that Fire Hydrants should be fixed in the village. Mr. Maclean explained what had been done by the Agwi Co. regarding Hydrants for their works and a let...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Cadland Estate and the Early Fire Brigades

- 2 Modernisation and War: The Beginnings of Organised Firefighting in Fawley

- 3 A New Fire Station at Fawley: The Hampshire Fire Brigade Years, 1977–92

- 4 New Names, New Challenges: Developing a Modern Fire & Rescue Service at Hardley, 1992–2014

- 5 Petrochemicals and Ammunition: Fawley’s Industrial Fire Brigades and Marchwood Defence Fire Station

- Bibliography

- Appendices

- Plates

- Copyright