- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The First World War claimed over 995, 000 British lives, and its legacy continues to be remembered today. Great War Britain: London offers an in-depth portrait of the capital and its people during the 'war to end all wars'. It describes the reaction to the war's outbreak; charts the experience of individuals who enlisted; shares many first-hand experiences, including tales of the Zeppelin raids and anti-German riots of the era; examines the work of local hospitals; and explores how the capital and its people coped with the transition to life in peacetime. Vividly illustrated with evocative images from the newspapers of the day, it commemorates the extraordinary bravery and sacrifice of London's residents between 1914 and 1918.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Great War Britain London: Remembering 1914-18 by Stuart Hallifax in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

LONDON GOES TO WAR

A huge crowd gathered outside Buckingham Palace to cheer King George V. Several thousand people – mainly young, middle class men – crowded around the Victoria Memorial and up Pall Mall in response to the news that Britain had entered ‘the European War’ on the side of France and ‘poor little Belgium’. It was the evening of 4 August 1914 and Britain was at war with Germany. The scene provides the classic image of 1914 ‘war enthusiasm’.

It came as a shock to most people. Until late July, most saw the escalation of tensions in the Balkans as simply another local conflict. Georgina Lee, a solicitor’s wife, wrote on 30 July that, ‘Grave rumours of a possible terrible conflict of Nations are on everybody’s lips and have been for some days.’ The next day, the London Stock Exchange was closed in reaction to Russia’s declaration of war against Austria-Hungary. On Saturday 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia and France mobilised its armed forces. The London correspondent of the New York Times reported that people now thought that the UK being ‘drawn into a great European war … is now a probability rather than a possibility’, but not yet inevitable. People’s opinions about the war were divided: in Trafalgar Square, for example, a large anti-war rally passed a resolution in favour of international solidarity and peace on Sunday the 2nd; that evening the first crowds began to gather outside Buckingham Palace. The government extended Monday’s bank holiday by two days to avoid a financial crisis when the stock markets reopened.

The German army’s invasion of Belgium on 3 August convinced most of those who wavered over British involvement to accept that the nation would and should take part in the conflict. An ultimatum was sent to the Germans on Tuesday 4 August, due to expire at 11 p.m. (midnight in Berlin), demanding that they leave Belgian soil and honour its neutrality. As the moment approached, vast crowds gathered in Westminster; when Big Ben struck the fateful hour the people celebrated the declaration of war. Over the next few days, crowds gathered outside Buckingham Palace and in the West End and, according to the New York Times, ‘Street vendors, shouting “Get your winning colors” [sic] were doing a rushing business, selling tiny Union Jacks, which the demonstrators wore on their coat lapels. There was also a brisk demand for French and Belgian flags.’

Elsewhere in London, crowds also gathered on 4 August to hear the news – there was of course no radio or television to inform them in their homes. In Fleet Street, crowds sang the British and French national anthems, but dispersed soon after the declaration of war was announced. In Ilford, according to the Ilford Recorder, ‘Little knots of people gathered outside the local Territorial offices, and at various points all the way down the High-road from Chadwell Heath to the Clock Tower and railway station … awaiting the fateful declaration of war, and it was not until long after the momentous hour of midnight had struck that they began to disperse.’

The vast majority of people did not join these crowds, and those who did were often there seeking news rather than cheering on a war. While many people backed entering the war, most were not enthusiastic about what it might bring. In Croydon (according to the borough’s war history Croydon and The Great War), ‘our people braced themselves for their greatest war effort. There was bewilderment at first, but there was no panic. … Nor was there any war-fever, that enthusiasm which finds expression in flag-flapping, cheering, boasting, and the singing of patriotic songs. It was, as one acute observer remarked, “a war without a cheer”; it was too serious a matter.’

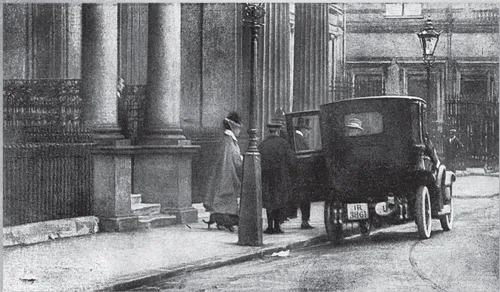

Germany’s Anglophile ambassador, Prince Lichnowsky, leaving London in August 1914.

On Carlton House Terrace, near the Mall, people watched in a ‘strange silence’ as the German ambassador prepared to leave the embassy. According to the Daily Mirror, one man booed but was shushed by the crowd and led away by the police. The remaining crowd watched quietly as a workman removed the brass plaque bearing the German eagle from the outside of the building.

We should not get too carried away with an image of complete calm in London, however. Some celebrated, while others were panic-buying food in case supplies ran short or prices went up, with the predictable result that prices rose and shops ran low on goods. The dominant attitude was resolve or resignation, though: the war had to be fought, had to be put up with, and had to be won.

How long the public felt the conflict would last is very hard to tell. The phrase ‘over by Christmas’, so beloved of historians and novelists, was only rarely used in 1914. If people did expect a short war, the mid-August appeal for 100,000 men to join the army ‘for three years or the duration’ told them how long the nation’s military leaders (especially Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War) felt the war could last. Whether people thought it would last a few months, a year, or three years, few – if any – imagined the eventual scale of the conflict and the ways that it would affect life in London.

London Before the War

In August 1914, London could be described as being the centre of the world: it was the capital of an empire that included a fifth of the world’s population and the centre of a system of trade that linked nations across the globe.

London had grown rapidly during the nineteenth century: from under 1 million people in 1801 to nearly 2 million in 1841 and over 4 million by 1891. By the start of the twentieth century, the growth of the city itself had almost stopped, but the urban area did not stop growing. While the county of London had reached 4.5 million in 1901, an ‘outer ring’ that made up the rest of Greater London grew from less than 1 million people in 1881 to 2 million in 1901. By 1911, it made up over a third of the 7.25 million people living in Greater London, the largest city on Earth.

The county of London – its new county hall on the South Bank was under construction in 1914 – was made up of the Cities of London and Westminster and twenty-eight metropolitan boroughs. The largest were Islington and Wandsworth, each with over 300,000 inhabitants; Lambeth, Camberwell and Stepney also had more than a quarter of a million inhabitants each. Most metropolitan boroughs had at least 85,000 inhabitants, with Chelsea and Holborn among the smallest, with only 66,000 and 50,000 residents respectively.

The outer ring of Greater London comprised: the whole of Middlesex (1.1 million people in 1911), which included Hendon, Ealing, Edmonton, Willesden and Finchley; areas of Surrey containing 500,000 people, including Croydon, Wimbledon, Barnes, Richmond and Epsom; Kent districts, including Beckenham, Bexley, Bromley and Erith, containing 172,000 people; the urban areas of south-west Essex containing Barking, East Ham, West Ham, Ilford, Walthamstow and Leyton, with over 800,000 residents; and an area of Hertfordshire with 55,000 inhabitants, including Watford, Barnet and Bushey.

Over such a broad area and so many people, there was of course a wide variety of labour and living conditions. Many of the Victorian suburbs that encircled the city in the ‘outer ring’ were home to clerks and professionals working in Central London, while the area in the docks either side of the Thames in East London included large numbers of dockers and warehousemen. East and West Ham were also home to a large amount of heavy industry (helpfully, the London rules on factory emissions did not apply over the River Lea in Essex), while the Royal Arsenal was situated on the other side of the river, at Woolwich.

Just under half of the 1.4 million male workers in the county of London worked in the service sector, and 12 per cent in transport (on rail, roads and the river, including the Port of London Authority). Another 16.6 per cent worked in commerce and 2.7 per cent in banking and insurance alone. Soldiers, sailors and marines made up another 15,000 workers. A third of London’s workers were women, primarily in service (over 200,000 domestic servants, plus 35,000 laundry workers and 30,000 charwomen) but a large number worked in the clothing industry, as well as an increasing number employed as clerks (32,000), teachers (18,000) and nurses (16,000). Two of the largest cross-London employers were the London County Council (LCC) and the Metropolitan Police. The latter broadly covered the area of Greater London, while the council was for the county itself. Both organisations employed large numbers of ex-servicemen.

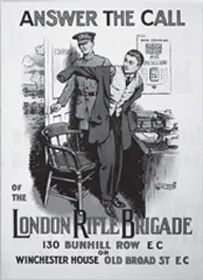

As well providing men for the regular army and housing many reservists (ex-servicemen who could be called up in an emergency), London was home to one of the few regiments of the British Army entirely made up of part-time soldiers – members of the Territorial Force, created in 1908 out of the old militias and volunteer corps of the previous century. The London Regiment had twenty-six battalions, including London-wide units such at the London Rifle Brigade, the Rangers and Queen Victoria’s Rifles, those for men with shared backgrounds and jobs like the London Scottish and the Civil Service Rifles, and those for areas, such as Blackheath and Woolwich, Hackney, and Camberwell (the First Surrey Rifles). There were also artillery and medical units, and the Honourable Artillery Company, which (despite its name) was an infantry unit based in the City of London. The Middlesex, Essex, East Surrey and West Surrey Regiments also had London-based territorial battalions. Although it had no Territorial Force battalions, the Royal Fusiliers were the ‘City of London Regiment’.

London Regiment battalions appealed directly to men to join their ranks, in this case for clerks to join the London Rifle Brigade. (Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-10960)

The Call to Arms

As soon as war was declared, the number of men volunteering for the armed forces overwhelmed the recruiting offices. Tens of thousands of Territorials and Reservists were reported for duty, but the more startling sight was that of civilians queuing for hours to join up. At first there were too few recruiting offices to cope with the enormous demand and the crowds became enormous – especially around the Central London recruiting office at Great Scotland Yard, off Whitehall. London Regiment battalions had their own recruiting offices, which were also overcrowded. City clerk Bernard Brookes waited for two or three hours on Buckingham Palace Road on 7 August to join the Queen’s Westminster Rifles (16th Londons): ‘After much swearing outside the building, we were “sworn in”’.

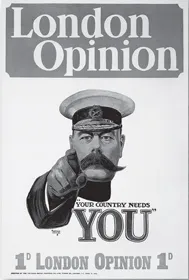

Alfred Leete’s famous image for the magazine London Opinion summed up Lord Kitchener’s call to arms. (Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-3858)

This ‘rush to the colours’ was an extraordinary increase on peacetime recruiting; within eleven days, more men had come forward to join the army than in any of the previous four years: almost 39,000 men (nearly 10,000 in London alone). New recruiting offices were established across the capital: on 7 August, The Times reported new offices opening in Camberwell, Islington, Battersea, Fulham, and Marylebone. The headquarters of German shipping firm Hamburg-Amerika on Cockspur Street also became a recruiting office. By 30 August, over 168,000 men had joined the army, including over 29,000 in London. An even greater recruiting boom was about to begin, though – well beyond anything seen before in the nation’s history.

On 23 August, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) first encountered the German Army at Mons in Belgium, only a few miles from Waterloo, where British and German forces had defeated Napoleon in 1815. Among the men who encountered the Germans at Mons was Lance Corporal Ernest Stretton from Islington; called up from the reserves in August 1914, he went straight into battle and was killed at Mons. The BEF suffered heavily in the fighting there and in the retreat to the Marne that followed it, but the Allies’ fighting retreat eventually brought the German offensive to a halt. Another reservist, William Hurcombe from Walworth, arrived in France on 26 August with the 20th Hussars and entered straight into the retreat from Mons; he survived that battle and numerous others through the rest of the war.

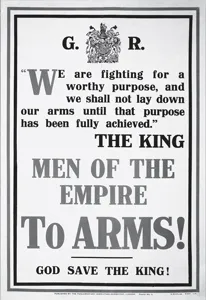

A typical parliamentary recruiting poster of autumn 1914, before the picture posters that characterised the later recruiting campaign. (Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-10872)

News soon got back to Britain about the losses at Mons. On 30 August, a report appeared in The Times stressing the threat to the very existence of the BEF and the need for more soldiers: recruiting rates for the army immediately rocketed. Men came forward in droves to help defend their nation. Helpfully, the timing also coincided with the end of harvest in rural areas and the peak of wartime unemployment in London; the recruitment boom also included those men who had earlier decided to join but first needed to sort out their personal affairs. The combination of these factors, public pressure and increased pro-recruiting rhetoric and speeches, brought in 4,000 recruits in London on 1 September (the next weekday after The Times’ report was published), more than double the rate of any previous day. In the first week of September, 24,814 men enlisted in London. Nationally, over 186,000 men joined up that week – more than in the whole of August, with over 33,000 on both the 4th and 5th of that month. Between 4 August and an increase in the height requirements on 11 September, 463,456 men joined up, including 67,276 in London.

A hopeful recruiting poster from the first winter of the Great War. (Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-10946)

This great rush of men came before the big national recruiting campaigns. In fact, it was in the wake of the steep decline in recruiting after 11 September that the national campaign really got going: London’s weekly enlistment rate fell from 15,000 to under 5,000 three weeks later (and the national rate fell from 100,000 to 15,000). The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC) – a national body with branches in every constituency – was formed at the height of the boom and began their work as enlistment declined, with their famous posters coming mainly in 1915. The most widely-known 1914 recruiting image is the ‘Kitchener Wants You’ poster, which was not in fact an official recruiting poster, nor was it very widely used at the time. The image was created by Alfred Lee...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Timeline

- Introduction

- 1 London Goes to War

- 2 The War Spirit

- 3 Work of War

- 4 News from the Front Line

- 5 Home Fires Burning

- 6 Armistice and Peace

- Select Bibliography

- Copyright