![]()

1

Origins

But Anthony Bek, bishop of Durham, put this question to him [Edward I]:

‘If Robert of Bruce were king of Scotland, where would Edward, king of England, be? For this Robert is of the noblest stock of all England, and, with him, the kingdom of Scotland is very strong in itself; and, in times gone by, a great deal of mischief has been wrought to the kings of England by those of Scotland.’

John of Fordun,

Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, 1873

The Bruces, like many others, were an adventurous Norman family who exploited opportunities to increase their landed wealth and status in the British Isles in the decades following William of Normandy’s conquest of England in 1066. Their original seat lay at Brix, near Cherbourg, but, by the early twelfth century, the first Robert Bruce had become Lord of Cleveland in North Yorkshire.

At some point after 1124, he was also granted the lordship of Annandale in south-west Scotland by the Scottish king, David I, who had grown up at the court of Henry I of England. Henry was married to David’s elder sister, Matilda, and was the ultimate owner of the lands south of the River Forth. This territory had once been the most northerly part of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria but was formally granted to the Scottish kings, who already controlled it, in 975.

The civil war that broke out after King Henry’s death in 1135 gave King David the excuse he needed to invade England, partly in defence of the claims of Henry’s daughter, Matilda, against her cousin, Stephen of Blois, and partly in pursuit of more territory. For the last twenty years of his reign the Scottish king held the three northern English counties of Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumberland. The gift of the lordship of Annandale with vice regal powers to Robert Bruce was not, therefore, about defending the border with England, which moved dramatically – if temporarily – some 100 miles further south during this period. Rather, it was intended that Bruce should keep an eye on the independent-minded lords of Galloway, west of Annandale, who had little enthusiasm for accepting the authority of the Scottish Crown.

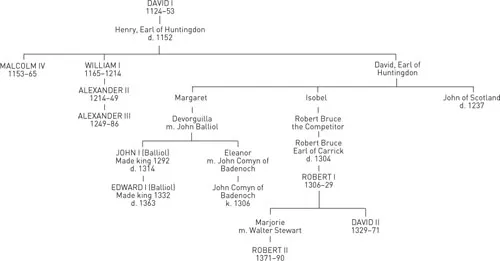

Though they continued to hold lands in England, this branch of the Bruce family soon rooted itself firmly in Scotland, becoming well respected and well rewarded. The wife of the third Robert Bruce was an illegitimate daughter of the Scottish king, William I, while his nephew, the fourth Robert, married Isobel, a great-granddaughter of King David I, around 1219. It was this marriage that would provide Robert and Isabella’s son – yet another Robert, nicknamed ‘the Competitor’ – with his claim to the throne of Scotland some seventy years later (see Family Tree).

In March 1286, the Scottish king, Alexander III, died riding through a storm to visit his new young queen. His three children by his first wife, Margaret, daughter of Henry III of England, had predeceased him. This left his granddaughter, a tiny Norwegian princess, as the only surviving direct heir. The Scottish nobility had already reluctantly promised to accept this Margaret as their future queen. However, Bruce the Competitor, now in his sixties, was adamant that he was a better choice as an adult male who, so he said, had been named heir to King Alexander II in the late 1230s, before the birth of the latter’s son, the future Alexander III.

As Margaret’s great-uncle and Scotland’s nearest neighbour, King Edward I of England naturally took an interest in these events, not least in order to ensure that the dispute did not degenerate into civil war and destabilise his northern border. Relations between the two kingdoms had improved dramatically over the last few decades, once Scotland had officially given up on claims to the northern counties of England, and intermarriage and the wealth generated by their wool trade had encouraged many Scots to seek property south of the border.

The Scots were well aware that Edward could be high-handed and single-minded: the English king had run roughshod over native law and custom when he conquered Wales in the 1280s. Nevertheless, given the need to safeguard Margaret’s future, the Scots were prepared to countenance her marriage to Edward’s son, Prince Edward, with the safeguard of a treaty defending Scotland’s integrity and independence.

However, the lynchpin of this agreement, the little princess herself, proved too delicate to survive the rigours of an autumnal crossing of the North Sea. She reached her father’s island of Orkney at the end of September 1290 and died there, the sombre news then being carried to the Scottish nobility and English envoys waiting to greet her at Scone, near Perth. The Scots now faced the very real threat of a violent squabble over the throne between Bruce the Competitor and his neighbour in south-west Scotland, John Balliol, Lord of Galloway, whose grandmother was the elder sister of Bruce’s mother, Isobel (see Family Tree).

Deciding how a new king should be chosen, and by whom, was never going to be easy. However, whether the Scots liked it or not, King Edward, a renowned lawmaker, was determined to preside over the court that would make that decision. No doubt by now he also saw Scotland’s vacant throne as an opportunity to extend his own power into the northern kingdom. Having encouraged other candidates to come forward and after making them all swear homage and fealty to him as Lord Superior of Scotland, King Edward’s court took over a year to make its decision. Finally, in November 1292, it was adjudged that the rightful ruler of the northern kingdom was not the Competitor, but John Balliol. Despite later assertions to the contrary, most Scots agreed.

This first Scottish King John soon found himself caught between Edward of England’s desire to turn his claims of lordship over the Scottish kingdom into specific obligations, and the desire of the Scots, led by Balliol’s relatives, the powerful Comyn family (see Family Tree), to deny and resist this. In 1295, the Comyns found enough support to stage a palace revolution, taking control of government away from King John, whom they believed was unwilling to risk war with King Edward in defence of Scotland’s independence. The next step was the conclusion of a treaty with England’s great enemy, Philip IV of France. Although the Scots had allied with the French against the English before, most notably during the reign of Edward’s grandfather, King John, this was the beginning of a longstanding alliance that, in theory at least, afforded both sides the protection of the other if attacked by England.

When Edward got wind of this he reacted furiously, though a man with a greater imagination would have recognised the extent to which the Scots had been pushed into the arms of the French by the English king’s own actions. The following year he brought a huge army north, sacked the great border port of Berwick, sent the Earl of Surrey to defeat the Scots at Dunbar, formally divested Balliol of his kingship and set up his own direct government of Scotland.

The Bruces had joined with the English against King John, but were bitterly disappointed at Edward’s quite unexpected resolve to keep the Scottish throne empty rather than award it to the Competitor’s son.4 Nevertheless, this Robert Bruce, the 6th Lord of Annandale, remained loyal to Edward I. But his son, the Earl of Carrick, joined resistance to English rule, which began to erupt spontaneously in various parts of Scotland from the late spring of 1297. For the seventh Robert Bruce, it was the beginning of a long and brutal contest that would ultimately be played for the highest of stakes.

![]()

2

The Testing Ground (1297–1306)

Hardly had a period of six months passed since the Scots had bound themselves by the above-mentioned solemn oath of fidelity and subjection to the king of the English, when the reviving malice of that perfidious [race] excited their minds to fresh sedition.

Chronicle of Lanercost, 1913

This youngest Robert Bruce – grandson of the Competitor and the future king – was born in 1274. Astonishingly, given that an epic poem thousands of lines long was written about him only some forty years after his death, we have nothing on which to base a description. A forensic reconstruction of what was long believed to be his skull, moulded from the original in the nineteenth century when a tomb in Dunfermline Abbey was temporarily reopened, presents us with a pudgy, square-faced man sporting what can only be described as a cauliflower nose. Unfortunately, doubt has recently been cast on whether this is actually King Robert, with academic opinion now favouring his great-great-great-great-grandfather, King David I.

In the dark days of November 1292, when it was no secret that John Balliol was about to be proclaimed as the rightful King of Scots, Bruce the Competitor proposed a series of extraordinary dynastic somersaults to his progeny. He knew that he was too old to fight this battle another day. So he charged his son – Earl of Carrick5 through his marriage to the heiress, Marjory – with taking the family’s claim to the throne forward in whatever way he could.

To that end, it was imperative that this middle Robert Bruce should hold no land in Scotland requiring him to swear homage and fealty – a solemn and binding oath – to the new Balliol king. The Competitor retained his vast lordship of Annandale, but Carrick was now passed on to his grandson, 18-year-old Robert, who became an earl. Shortly thereafter, the latter married Isobel, daughter of Donald, Earl of Mar – a close ally of his grandfather. Though Isobel was dead by 1297, the couple had a daughter, named Marjory after Carrick’s mother.

Around the same time, the young earl decided to try a different tack, rather than hoping, like his father, that loyalty to Edward I would help them to fulfil their ambitions. What Carrick was taking astute advantage of was the fact that most of the Comyns – Scotland’s most powerful political family – had been imprisoned or forced into exile in England for their part in fighting against Edward on Balliol’s behalf in 1296.

This was a power vacuum that young Carrick now tried to exploit. In the early summer of 1297, he, along with his friend and neighbouring lord, James the Steward, and the powerful Bishop of Glasgow, Robert Wishart, called out their armies in protest at King Edward’s demands that ‘the middling sort’ of Scotland should fight with him in his impending campaign against France. This was viewed as an outrageous and potentially debilitating imposition on men who, though not nationally prominent, were nonetheless important leaders in their own communities. At the same time, Carrick and his allies were positioning themselves as the voice of Scotland’s political community.

The timing was well planned too, coming as it did not long after William Wallace launched the first known attack on English officials at Lanark, south-east of Glasgow, on 3 May 1297. Initially, the Scots were only loosely co-ordinated. However, the prospect of a group of senior noblemen joining the unrest seriously alarmed the English government based in Berwick and an army sent out against them spent most of June negotiating their surrender. As part of that agreement, Carrick and the others were supposed to hand over hostages: in the earl’s case, his baby daughter. Over the coming months, considerable pressure – including the ravaging of his father’s lordship of Annandale (inherited in 1295) – was put upon the earl to comply, but he never gave Marjory up.

Despite this aristocratic capitulation, Andrew Murray and William Wallace were still attacking English garrisons and Edward was sufficiently concerned to countenance the release of members of the Comyn family explicitly to deal with them. The latter, like many of the Scottish nobility, sat on the fence until the Scottish victory at Stirling Bridge against the Earl of Surrey in September 1297. With almost all English garrisons expelled from the country, it made sense to revive the position of Guardian to run those parts of Scotland not under English control until King John was able to return from imprisonment in England. With Andrew Murray dead from his wounds, William Wallace was the obvious candidate to hold the office, despite not coming from a noble family. He earned himself a knighthood at the same time, reputedly – though there is no evidence for it – at the hands of Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick. Ten months later, however, Sir William was defeated by King Edward at Falkirk and, since success in warfare was the sole reason for his elevation, he was forced to resign as Guardian. By the end of 1298, Sir John Comyn, the younger, of Badenoch – King John’s nephew – and Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, had become joint Guardians in an uneasy compromise between these two powerful families.

It did not take long for the two young men to come to blows as both sought to take advantage of the possibilities afforded by an absent king. The year 1299 was comparatively quiet, since Edward was focused on his marriage to Philip of France’s sister, Marguerite, rather than a campaign in Scotland. In August, Scotland’s leaders, including the two Guardians, dared to meet in Selkirk Forest, in the heart of English-held territory. An altercation began between one of Comyn’s men and Sir Malcolm Wallace – the former Guardian’s elder brother, who was part of Carrick’s retinue – because Sir William was known to be going to the Continent to lobby for support on behalf of King John without Sir John Comyn’s permission.

Word of the scuffle reached Comyn and he immediately seized Carrick by the throat, crying treason, while his cousin, the Earl of Buchan, rounded on the Bishop of St Andrews, William Lamberton. Cooler heads stepped in to calm things down and, in light of news of a raid by pro-English Scots in the north that needed their immediate attention, it was agreed that Lamberton shoul...