- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Story of Southampton

About this book

The Story of Southampton is a long overdue and engaging general history of the city, from the earliest times to the present day, taking into account its unique architectural development and heritage. It not only looks at the local history, but also how those events had a wider significance – especially in relation to the sea and communications. Peter Neal has an eye for a telling anecdote, and this, together with his lively tone and authoritative research, will make the book appealing to anyone who is seeking to find out more about this fascinating city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Story of Southampton by Peter Neal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

two

CANUTE, CONQUEST, CASTLE

As the settlement began to recover, it relocated to the southern part of the west of the peninsula. The precise way in which the settlement became known as Southampton is now unlikely to be proved definitively, but a number of theories have been expressed. A concept that the ‘South’ prefix was added to distinguish the town from Northampton is now disregarded: it may merely be that the newly occupied area was simply south of the previous Hamtun settlement. Confusingly, however, up until the sixteenth century the inhabitants still referred to the previous site of Hamwic as ‘Old Hampton’. The move could at least partially be attributed to shipping conditions: the River Itchen was silting up on the peninsula’s eastern shore, and furthermore the increasing size of seagoing vessels meant that the River Test to the west was more easily navigable.

A period of relative peace came to an end shortly after the accession of Ethelred in 978. Southampton was attacked in 980 and again the following year, with significant numbers of the townspeople killed or captured. In 994, the Danish king, Sweyn, chose Southampton as the location of a winter base for his troops, who arrived in almost 100 ships and forcefully entered and occupied the town. Sweyn’s men had originally targeted London with limited success, and had subsequently plundered the coasts of Kent and Sussex en route to Hampshire. Unable to sustain a worthwhile defence, Ethelred agreed to pay the Vikings rather than suffer any further at their hands, and the invaders retired to Southampton while they waited for their remuneration – menaces money on a grand scale.

Despite this pact, the Danes raided Southampton and the Isle of Wight again in 1001, and received a yet greater payment in exchange for their withdrawal. Evidently realising that there was good money to be made from periodic violent forays against Ethelred’s meagre defences, the Danes repeated the manoeuvre in 1006 and 1012, pocketing a larger windfall each time. By 1013, the king was a fugitive from Sweyn and barely more popular with his own people, and he escaped via Southampton and the Isle of Wight to northern France. In the aftermath of Sweyn’s victory, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle observed that ‘all the nation regarded him as full king’, but he died the following year and Ethelred returned. Sweyn’s son, Canute, withdrew to Denmark, but at the time of Ethelred’s death, in 1016, he was in Southampton, where he summoned the witan (a council of the wise men of Wessex) to him. The witan gave its blessing to Canute, but when Ethelred’s son, Edmund, reappeared the Council’s allegiance was tested; and eventually the kingdom was divided between the two contenders for the throne. However, before the end of 1016, Edmund too was dead and Canute became ruler of the entire country.

Wessex became the hub of Canute’s kingdom, with Winchester retaining the significance it had enjoyed since Roman times. Both Winchester and Southampton experienced newfound periods of prosperity under Canute, who went on to eschew violent conquest in favour of a more temperate policy. It was during Canute’s years in power that the relocation of the town’s core to the area later enclosed by the town walls was consolidated. The infamous anecdote that Canute attempted to repel the tide at a Southampton shore is now considered by most historians to be the stuff of myth and legend. Nevertheless, both this tale and Canute’s indisputable association with the town and surrounding area have seen his name given to roads and buildings for many years.

The town’s connection to the English monarch continued upon Canute’s death in 1035, when another of Ethelred’s sons, Edward, landed at the town on his return from France. He brought with him considerable forces, but did not become king until the death of Canute’s son, Harthacnut, in 1042; he was known as Edward the Confessor. Edward died in 1066, and the witan chose Harold as his successor. Before the end of the year, William of Normandy attacked England, landing at Pevensey in East Sussex. Harold was killed at the ensuing Battle of Hastings. When William’s invasion reached London it was met with submission rather than resistance, and he was formally made king at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, at the end of an especially eventful year.

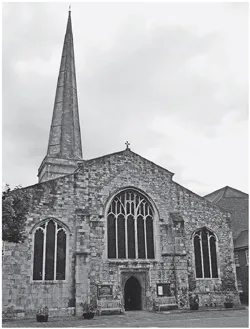

In order to know what his newly acquired kingdom contained, William commissioned a huge inventory. The Domesday Book was completed and presented to him in 1086. It recorded that Southampton was populated by seventy-six ‘original’ householders, and that a further ninety-six had settled in the town since the Conquest. The new residents were divided into approximately two-thirds French and one-third English, and the area in which the former resided has been immortalised with the naming of French Street. Likewise there was also English Street, which was renamed High Street in the sixteenth century. In the post-Conquest period, the town was regarded as being split into two boroughs, each with its own church for the use of French or English worshippers. The French church, St Michael’s, was built not long after the Conquest, and was named in honour of the patron saint of Normandy. There have been extensive adaptations over the years, such as the spire that now sits on the Norman tower, but many original features remain, especially internally.

St Michael’s church, 2011.

The Domesday record of Southampton omitted other residents of the town, however – specifically the poor or labouring class, who were seen as statistically irrelevant as they contributed nothing in taxation. William’s grand itinerary, therefore, contains no absolute figure for Southampton’s population in the late eleventh century, but around 1,000 can be considered a reasonable estimate. The town was thus not a great metropolis – Bristol was over three times larger and Winchester up to seven times – but it continued to enjoy a comparatively prosperous period. This affluence was common to a number of ports on the South Coast of England, as the links with William’s homeland remained important. Southampton’s geographical position was also significant, being approximately the same distance from London and Bristol, and a key point on the route between Normandy and Winchester.

Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, married Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152, and two years later became the King of England upon the death of King Stephen. The marriage with Eleanor meant that in addition to the existing trade with Normandy, new commerce sprang up between England and vineyards in the Gascony area of south-west France. Southampton quickly became a prominent wine port, and the wine trade remained an important factor in the town’s economy for several hundred years. Meanwhile, English beer on occasion travelled in the opposite direction. These business links with France, combined with Southampton’s French population, meant that some merchants in the town (and possibly Winchester as well) were likely to have been bilingual.

From about this time, Southampton’s defences were enhanced in accordance with its growing significance as a commercial port. As in a number of other towns, the Normans built a castle in Southampton after the Conquest, both as a signal of their power and as a base from which to maintain it. Since the monarchs of the time still oversaw kingdoms on both sides of the Channel, the town was a key embarkation point. The castle was located at the north end of Bull Street (today’s Bugle Street), and subsequently gave its name to nearby Castle Lane. It was first mentioned in a document in 1153, but it is likely that a fortification on the site was originally built in the reign of William the Conqueror. This is suggested by the fact that coins from the era have been found at the location, and that the motte (the man-made earthen mound on which the castle was built) was large, consistent with others constructed soon after the Conquest. Furthermore, one of William’s chief aides, William FitzOsbern, spent a good deal of time in Hampshire, and initiated the building of many castles throughout the country. His schemes sometimes made use of forced labour, and while FitzOsbern was successful in his endeavours, some of his methods have been brought into question.

The motte would have been surrounded by a ditch up to 65ft wide and a wooden fence, and originally the castle keep itself would also have been made of timber. Records show that between 1155 and 1162, over £50 was spent on building...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction

- One Beginnings

- Two Canute, Conquest, Castle

- Three Ransack & Recovery

- Four European Trade

- Five Mayflower, Civil War & Plague

- Six Spa Town

- Seven Military Might

- Eight Growth & Reform

- Nine Railway & Docks

- Ten The Shipping Companies

- Eleven Expansion of the Town & Docks

- Twelve RMS Titanic & the First World War

- Thirteen The New Docks & Civic Centre

- Fourteen Bloodied but Unbeaten

- Fifteen City Status

- Bibliography

- Copyright