eBook - ePub

In Search of the Zeppelin War

The Archaeology of the First Blitz

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is the story of the first Blitz and the first Battle of Britain, featuring a full account of the first Zeppelin crash site excavation and also covering airfields, gun sites, searchlights, and radio listening posts. The book features contemporary accounts and archive photographs alongside the reports and photographs from the excavations, including Hunstanton, Monkhams, Chingford and North Weald Basset, the Lea Valley, Potters Bar and Theberton. Written in collaboration between academic archaeologists and aviation enthusiasts/metal detectorists, this fascinating project has also been the subject of a BBC2 Timewatch documentary.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Destruction

of Zeppelin L48

By 2.30 on the morning of 17 June 1917, the German Zeppelin L48, flying north along the coast beyond Harwich, was in trouble. One of a new generation of super ‘height-climber’ Zeppelins, L48 was on its maiden bombing mission to Britain. The mission was doomed from the start. Six Zeppelins had been assigned to the raid, but two had been prevented from leaving their sheds by stiff crosswinds, and two others had been forced to return home early with engine trouble. Only L42 and L48 had made it to the British coast. They got no further. A thunderstorm raged inland, and all hope of reaching London, the principal target of opportunity, was quickly abandoned: the weather had blown shut the small window of time given to the airships to complete their mission.

For Zeppelins were machines of the night – stealth-bombers that relied, ideally, on the darkness of long moonless nights for safety, often launching their bombing runs with engines shut down, drifting silently with the wind, the underbellies of the latest models camouflaged with black paint. Yet Peter Strasser, Germany’s iron-hard airship commander-in-chief, had ordered this raid with the shortest night of the year less than a week away. Some had doubted his wisdom. Some considered the mission little short of suicidal. With only a few hours of half-light, the airships could not afford to linger over enemy territory, for to be caught in daylight would be to fall almost certain prey to Britain’s increasingly efficient and numerous home-defence fighter aircraft.

Height-climbers like L42 and L48 had been developed in direct response to this threat. The previous autumn, in the space of just a month, four state-of-the-art airships had been shot down by British night-fighters. The German High Command, though badly shaken, had kept its nerve and resolved to invest in a new generation of machines able to reach altitudes beyond the range of the British defences. Everything that could be done in the new design to reduce weight was done. The old three-engine rear gondola with outrigger brackets for propellers was replaced by a twin-engine version powering a single propeller. Fuel capacity was cut from 36 to 30 hours’ flying time. The number of bomb release mechanisms was halved. The hull structure was lightened. The control gondola became more compact. All accommodation and comforts for the crew were eliminated. This new generation of Zeppelins – the ‘Forties’ – were thus able to reach altitudes above 20,000ft, around 3,000ft higher than their predecessors, the ‘Thirties’.

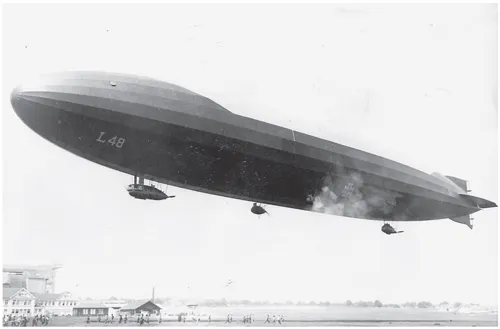

The L48 at Friedrichshafen in May 1917. The mighty Zeppelin was 645ft long – more than two football pitches in length, or three Jumbo 747s nose-to-tail. Having been stripped of every bit of excess weight possible to help it climb higher, it weighed in at just over 25 tons – whereas the average Jumbo weighs 390 tons at take-off. Such was L48’s volume that it could have held 687,400 gallons of water – the equivalent of more than eighteen Olympic-size swimming pools. (D.H. Robinson via Ray Rimell)

The height-climbers had made their debut over Britain on 16 March 1917. There had been problems from the beginning. Four miles up, higher than any aviators had ever ascended, the German aircrew entered the eerie world of the sub-stratosphere. Here, machines were buffeted by gales unknown to weather stations on the ground. Engines seized up, metalwork shattered, and instruments failed in the bitter cold. The aircrew were afflicted by pounding headaches, nausea, exhaustion, and frostbite. Moreover, from their icy nocturnal perches, the Zeppelin captains could discern almost nothing of the ground, and both navigation and targeting became little more than lotteries. The average damage inflicted by a raider slumped from around £6,500 in summer 1916 to around £2,000 now.

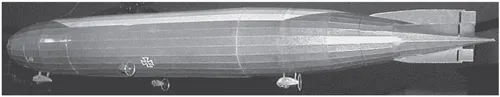

A model of L48. Note the tiny size of the gondolas suspended below the Zeppelin’s huge canopy. The forward one was the control gondola, the rear one the main engine gondola, the two small ones amidships also engine gondolas.

L48 in ‘night camouflage’ on a trial flight. As home defences improved, the undersides of Zeppelins were painted with black dope to make it harder for enemy searchlights to pick them up.

An official military shot of L48, showing the two amidships engine gondolas, and the black cross of Imperial Germany.

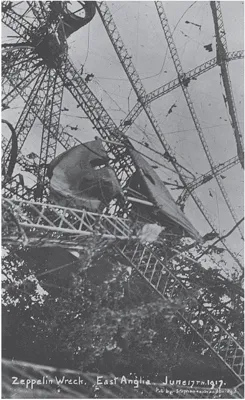

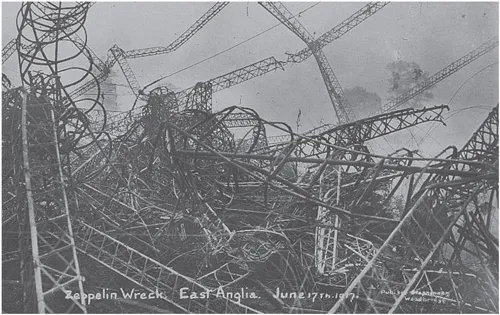

A contemporary postcard showing the wreckage of L48 in Crofts Field at Theberton Hall Farm – a tangled mass of lightweight duralumin girders.

Thus, in the early hours of 17 June, with the pale glow of dawn already showing in the east, L48 was in trouble. Approaching the East Anglian coast around midnight, in the bitter cold at 18,000ft, first the starboard engine had failed, then the forward engine had begun knocking badly, and finally the magnetic compass had frozen. Giving up on London, Kapitänleutnant Franz Georg Eichler ordered a bombing run over Harwich prior to turning for home. But the twenty-four recorded bombs dropped by L48 that night all landed harmlessly in Suffolk fields.

By then, the home defence was on full alert. During the bombing run, two dozen searchlights had snapped on, thrusting long, luminous, groping arms into the night sky. Then one of the arms caught the airship and held it in a circle of light. The others had quickly closed into a tight cone, bathing the airship in bright, dazzling light, illuminating its black underbelly, strung with tiny gondolas, and emblazoned with the serial number and the black cross of Imperial Germany. ‘Instantly it began to thunder and lightning below,’ recalled Leutnant zur See Otto Mieth, the airship first officer, ‘as if an inferno had been let loose. Hundreds of guns fired simultaneously, their flashes twinkling like fireflies in the blackness beneath. Shells whizzed past and exploded. Shrapnel flew. The ship was enveloped in a cloud of gas, smoke, and flying missiles.’

Fear twisted inside every man aboard. Weariness, the cold, the constant gasping for air were subsumed by the imminence of the fate most feared by men who fight in the air: burning to death in a tangle of flaming wreckage. For what was an airship but a vast gas-filled incendiary bomb? L48 flew only because it was lighter than air. A huge lightweight framework of duralumin girders and steel wires supported a row of eighteen gas-bags made of animal membrane, cotton fabric, and glue, which, when inflated, contained two million cubic feet of hydrogen gas and filled almost the entire interior space. Stretched over the exterior of the framework was an envelope of light cotton fabric, coated in dope, laced together, and pulled taut. The keel of the duralumin framework formed a gangway running the length of the ship, and here were stowed water-ballast sacks, petrol tanks, and bomb racks. Slung beneath the keel were the forward control gondola and three engine gondolas, a large one towards the rear, two smaller ones amidships. The airship’s five engines (with two in the rear gondola) powered four propellers, one at the back of each gondola, and afforded a maximum speed of 67mph. Direction was controlled by cables which ran from the forward gondola to movable rudders and elevators attached to the ends of the four tail-fins.

At almost 200m long and 24m across, L48 was bigger than a battleship. She was, at once, a triumph of modern engineering, a symbol of industrialised war, and a sinister black force in the night sky threatening death and destruction to those below. For the men who served her she was also something more: a huge, slow-moving, technically unreliable and highly vulnerable flying machine, with the potential to be transformed in an instant into a vast celestial funeral pyre.

The contorted wreckage of L48 captured in another contemporary postcard. Amid the structural girders are two sections of ladder by which aircrew would have moved between the gondolas and the hull. Commemorative or ‘newsy’ postcards such as this were commonplace at that time.

There were nineteen men aboard that night. Half were machinists serving the engines, which required constant maintenance and occasional in-flight repairs. Though warmed by the engines during the long hours of flight, a head-splitting roar and an asphyxiating mix of oil and exhaust fumes assailed the machinists. Meanwhile, in the forward control gondola, bitter cold assailed the airship’s three officers – Korvettenkapitän Viktor Schütze, the commander of naval airships and leader of the raid, Kapitänleutnant Eichler, the commander of L48, and Leutnant zur See Mieth, his executive officer. Also in the control car were two petty officers operating rudders and elevators, two more working in a soundproof wireless compartment, and a navigator. Despite it being high summer, temperatures could sink below -25°C. The crew wore thick woollen underwear, blue naval uniforms, leather overalls, fur overcoats, scarves, goggles, leather helmets, thick gloves of leather and wool, and large felt overshoes covering their boots. They were sustained by generous rations of bread, sausage, stew, chocolate, and thermos flasks of strong coffee. Thus did the pioneers of military aviation enter the strange new combat zone of the upper skies.

L48 completed its bombing run unscathed. She then dropped to 13,000ft and headed for home. But the frozen compass misled the navigator, and instead of setting a course east, L48 went north, along rather than away from the British coast. By the time the error was detected, the forward engine had failed, and the airship’s speed, dependent now on three engines, was well down. Eichler radioed stations in the German Bight for bearings, and with them came the information that he would find useful tailwinds to assist his speed if he descended to 11,000ft. But the telephone lines that fed information from radio stations and observer posts to home-defence headquarters on the ground, and from there to the searchlights, AA batteries, and fighter airfields, were already humming. The lower skies were filling with hostile aircraft as they brightened with approaching dawn.

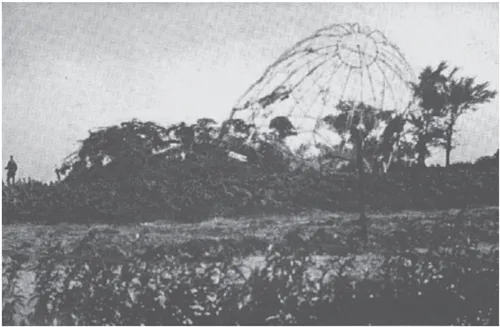

A postcard showing the wreckage of L48 in Crofts Field, including the hedge which was later grubbed out, guarded by soldiers.

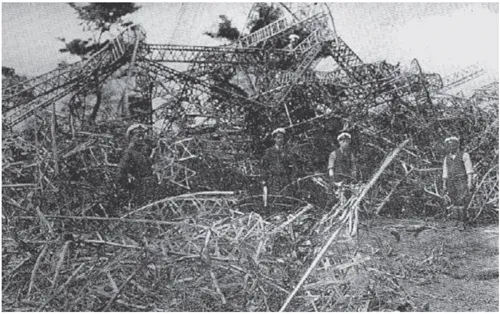

Military salvage team at work on the debris of L48. The wreckage was of huge importance to the war effort, providing much information about the workings of the Zeppelins. The salvage teams reduced the wreck to manageable sizes for transporting by road to a special goods-train at Leiston Rail Station (three miles away). From there the remains were taken to The Royal Aircraft Establishment (or RAE) at Farnborough, where it was hoped valuable data could be collected to help Britain in her own efforts at designing successful military and civil airships.

At 1.55a.m. Second Lieutenant Frank Holder and Sergeant Sydney Ashby ascended from the Royal Flying Corps airfield at Orfordness in an FE2b night-fighter (see image here). Built of wood, wire and canvas, First World War aircraft were flimsy, low-powered, and often lethally dangerous to fly. As well as being slow, difficult to manoeuvre, and liable to develop technical faults in flight, they could take up to half an hour to climb to maximum altitude. The FE2b had a maximum speed of 92mph, an altitude ceiling of 11,000ft, and could stay in the air for only two hours thirty minutes. A pusher-biplane, with engine and propeller behind the cockpit, it had the appearance of a huge bug, with a stubby, round-nosed fuselage, and open struts and wires connecting this to the tail-plane. An observer sat in the nose, the pilot in a raised cockpit behind, and both were armed with machine-guns.

Holder first sighted L48 at about 2.10a.m., during her bombing run over Harwich under heavy anti-aircraft fire. The British had already developed a distinctive air-war doctrine: air supremacy – and thereby security from aerial bombardment – was to be achieved by relentless efforts to locate and destroy enemy aircraft. The British fighters were hunter-killers: once an airship had been sighted, their job was to pursue and attack just as long as they had operational range. Holder now did exactly that. He attempted to close with L48 over Harwich, but he could not achieve the necessary height, his and Ashby’s fire was ineffective, and his own machine-gun promptly jammed.

Following as L48 headed north, however, Holder began to gain on the airship as she was slowed by engine failure and descended in an effort to gain speed. Two other British fighters were also closing in. Flight Commander Henry Saundby had taken off from Orfordness at 2.55a.m. in a DH2 pusher-biplane (see image here). The DH2 had a similar bug-like appearance to Holder’s FE2b, but it was a single-seater, considerably smaller – with a wingspan of only 8.5m as against 14.5m – and performed rather better. Meantime, Second Lieutenant ‘Don’ Watkins had taken off from Goldhanger in a BE12 (see image here). A conventional single-seater aircraft with engine and propeller at the front, the BE12 was exceptionally stable, affording the pilot, who had to control the plane while doubling as machine-gunner, a secure firing platform amid the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The Destruction of Zeppelin L48

- 2 In Search of the Zeppelin War

- 3 Weapons of Mass Destruction

- 4 ‘Take Air-Raid Action’: the Early Warning System

- 5 London’s Ring of Iron

- 6 Lights and Guns

- 7 Airfields and Fighters

- 8 The Crash Site

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Summary of First Blitz Project Fieldwork

- Appendix 2 First Blitz Project Personnel and Acknowledgements

- Suggested Further Reading

- Getting Involved

- Plates

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access In Search of the Zeppelin War by Neil Faulkner,Nadia Durrani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia militare e marittima. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.