![]()

• 1 •

BIRTH AND BACKGROUND

THE WODEHOUSE FAMILY IS an old one; Sir John Wodehouse won his knighthood at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Established at Kimberley in Norfolk since the fifteenth century, the heads of the family served as Members of Parliament and were raised to a baronetcy in 1611. In 1797 they were promoted to the rank of baron, and in 1866 the head of the family was created the Earl of Kimberley. Wodehouse’s grandfather, a grandson of the 3rd Baron, fought at Waterloo.

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (known to his family and friends as ‘Plum’ throughout his life) was born on 15 October 1881 at 59 Epsom Road, Guildford, Surrey (there is now a plaque on the house). His mother, Eleanor Deane Wodehouse, home from Hong Kong, was staying with a sister a few miles away and was paying a social call on a friend when Wodehouse made his appearance. Soon afterwards, his mother took him out to Hong Kong, where her husband, Henry Ernest Wodehouse, was a magistrate. There the baby Pelham joined his two elder brothers, Philip Peveril (born 1877) and Ernest Armine (born 1879). A younger brother, Richard Lancelot, was born in 1892.

In 1883 the boys were brought back to England and put in the charge of a Miss Roper, who lived in Bath near Wodehouse’s grandparents. In 1885–86 they became boarders at a small establishment run by two sisters, the Misses Prince, at The Chalet, St Peter’s Road, South Croydon, which became today’s Elmhurst School. After a short period at Elizabeth College, Guernsey, Plum was sent to a small school in Dover. It was named Malvern House – the name Wodehouse used later for the prep school attended by Bertie Wooster.

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (right) with his brothers Ernest Armine (left) and Philip Peveril (centre). (Courtesy of Sir Edward Cazalet and the Wodehouse Estate)

Because his parents were in Hong Kong, Wodehouse saw very little of them until he reached the age of 15. In those days, when travel to the Far East took several weeks, home leave was granted only every four years or so. And since there was no air conditioning and European children were very vulnerable to tropical diseases, they were sent home to be looked after by relatives. Today this seems heartless, but then it was common for children whose parents served in distant parts of the Empire. The result was that Wodehouse was looked after by a succession of aunts and uncles whom he came to know better than he did his own parents.

Since Wodehouse’s father and mother both came from large families, he possessed no fewer than twenty aunts and fifteen uncles. These included four clergymen and many service officers and colonial administrators. Few were wealthy, but they were all what was then known as ‘gentry’ and were very conscious of the fact.

Where’s your pride? Have you forgotten your illustrious ancestors? There was a Wooster at the time of the Crusades who would have won the Battle of Joppa single-handed, if he hadn’t fallen off his horse. (Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen)

During much of his childhood, Wodehouse lived at Cheney Court in Wiltshire, the home of his grandmother and four spinster aunts. He recalled accompanying his aunts when they paid formal calls at the Big Houses in the area and the hostesses tactfully suggesting that young Pelham might prefer to have his tea in the Servants’ Hall. It gave him an early insight into ‘life below stairs’ that he would put to good use later.

When he came to live in London as a bank clerk and, later, a young journalist, there were uncles and aunts in Kensington and Knightsbridge who made sure he fulfilled what they considered his social obligations, whether he liked it or not. This meant donning a top hat, frock coat, gloves and spats, and accompanying his aunts when they paid formal calls or attended ‘At Homes’, or attiring himself in evening dress (white tie and tails) to attend dinners where the guests included members of the peerage and, on one occasion, an Italian prince. It was very different from his usual routine as a young freelance writer, but it was a social duty he could not avoid.

The influence of these uncles and aunts cannot be overestimated in Wodehouse’s stories. He realised early on that an overbearing father or mother cannot be a figure of fun; an overbearing aunt or uncle can, and this became a permanent factor, especially in the stories featuring Bertie Wooster. In a letter (14 January 1955), he wrote: ‘Aunt Agatha is definitely my Aunt Mary [Mary Deane] who was the scourge of my childhood.’

On the cue ‘five aunts’ I had given at the knees a trifle, for the thought of being confronted with such a solid gaggle of aunts, even if those of another, was an unnerving one. Reminding myself that in this life it is not aunts that matter, but the courage that one brings to them, I pulled myself together. (The Mating Season)

Towards the end of his long life, Wodehouse freely admitted he was writing of a world that ended in 1914, a world of country houses, eccentric aristocrats and young men with menservants and nothing to do but enjoy themselves. But it was the world he had grown up in; what he did was to see the funny side of it and exaggerate features his readers would recognise.

While we think of Bertie Wooster and his friends as typical young men of the 1920s and ’30s, that is because Wodehouse updated them so well. Their clothing, their sports cars and their speech change through the years, following faithfully the fashions of the day, and after 1945, in Ring for Jeeves and Cocktail Time, we read of the problems of those condemned to live in large country houses without the money to run them. But the same happy spirit runs through them all.

![]()

• 2 •

DULWICH AND THE BANK

From my earliest years I had always wanted to be a writer. I started turning out the stuff at the age of five. (What I was doing before that, I don’t remember. Just loafing, I suppose.) (Over Seventy)

ON 2 MAY 1894, Wodehouse entered Dulwich College, South London, which his brother Armine had entered two years earlier. Wodehouse loved the school from the moment he saw it and followed its fortunes for the rest of his life. Some have said he had a fixation on his old school and never grew out of it. Perhaps so, but it should be remembered Dulwich was his first real home. Until he was 15, he only saw his parents at three- or four-year intervals and never developed the normal child-parent bonds. Dulwich was the first stable environment he knew. It was a place with a routine of order and discipline – factors every boy needs. He was successful there; he became a prefect, played for the cricket and rugby teams, boxed, and was an editor of the school magazine The Alleynian.

Years later, Wodehouse noted how lucky he had been to attend in what was a golden period for the school. The headmaster, A.H. Gilkes, inspired not only the staff but the boys as well, and Dulwich became known for the number of scholarships it won to Oxford and Cambridge. Wodehouse was not alone in his affection for Dulwich; a remarkable number of boys went to university and promptly returned to their old school as teachers. When Wodehouse was living in London, he attended every important Dulwich rugby and cricket match and later arranged his trips from France to coincide with such matches. He also used the area immediately around the school as Valley Fields, a setting for many of his later stories.

From the fact that he spoke as if he had a hot potato in his mouth without getting the raspberry from the lads in the ringside seats, I deduced he must be the headmaster. (Right Ho, Jeeves)

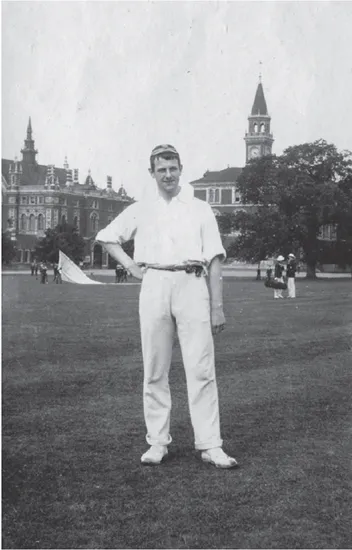

A young Wodehouse on the cricket pitch at Dulwich College. (With kind permission of the Governors of Dulwich College)

‘You don’t know anything about anything,’ Mr. Pynsent pointed out gently. ‘It is the effect of your English public-school education.’ (Sam the Sudden)

One of the school libraries is now named after him, and his desk and typewriter stand in one corner.

In his last year at Dulwich (1899–1900), Wodehouse was working hard for a scholarship to Oxford. In early 1900, however, his father informed him he would be unable to pay the university fees and had secured a place for him as a clerk at the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, which trained its managerial staff in London. After a few years in the Lombard Street office, they went out to the Far East as assistant managers. Most of the young clerks were, like Wodehouse, from public schools, and although he claimed he never really got to terms with the technical side of banking, he played rugby and cricket for the bank and got on well with his fellows.

But he was determined to make his living as a writer and spent his evenings writing articles on schools like Malvern and Tonbridge for The Public School Magazine and such topics as football at Dulwich. They did not bring in much money, perhaps half a guinea each, but the average wage then was about £1.40 a week.

He also began submitting humorous pieces and verses to newspapers and magazines. He was fortunate in his market. There was no radio, film or television then, and there were over 700 weekly and monthly ‘story’ magazines in the UK, while London had nineteen morning and ten evening papers.

Perceval Graves, elder brother of the poet Robert Graves, shared lodgings in Walpole Street, Chelsea, with Wodehouse and remembered him leaving the table immediately after the evening meal and writing, writing, writing in the bathroom until midnight. In August 1901 he went to see W. Beach-Thomas, who had been a Dulwich master and who was then working on the ‘By The Way’ column of The Globe evening newspaper. Wodehouse secured an occasional day’s work on the column and continued to submit jokes and short articles to a wide variety of magazines. In September 1902 he was offered five weeks’ work on The Globe, upon which he made the decision to leave the bank and become a freelance writer.

He was not yet 21 years old, but the first of what were to be many contributions to Punch appeared on 17 September 1902, followed by the publication of his first book, The Pothunters, the next day. Over the next eleven months his work appeared in many magazines and he secured more work on The Globe’s ‘By The Way’ column, culminating in the offer of regular employment in August 1903. He was on his way.

![]()

• 3 •

THE GLOBE, THE SCHOOL STORIES AND PSMITH

THE ‘BY THE WAY’ column appeared on the front page of The Globe, a London evening newspaper, and consisted of humo...