![]()

PART 1

Possible Childhoods of The Dublin King

![]()

1

Richard, Duke of York

About fifteen years after the death of King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth, Bernard André (1450–1522), a French Augustinian friar and poet from Toulouse, who is also sometimes referred to under the Latin form of his surname as Andreas, and who was employed by Henry VII, wrote a history of the new king’s reign. This is often called by its abbreviated Latin title, Historia Henrici Septimi. André’s history of Henry VII offered the following account of the rebellion of 1487:

While the dire death of King Edward’s sons was still a fresh wound, behold, some seditious fellows devised another new crime, and so that they might cloak their fiction with some misrepresentation, in their evilmindedness they gave out that some base-born boy, the son of a baker or tailor, was the son of Edward IV. Their boldness had them in its grip to the point that out of the hatred they had conceived for their king they had no fear of God or Man. Thus, in accordance with the scheme they had hatched, rumor had it that Edward’s second son had been crowned king in Ireland. And when this rumor was brought to the king, in his wisdom he elicited all the facts from the men who had informed him: namely, he sagely discerned how and by whom the boy had been brought there, where he had been raised, where he had lingered for such a long time, what friends he had, and many other things of the same kind. In accordance with the variety of developments, various messengers were sent out, and finally [ — ],1 who said that he could easily divine whether the boy was what he claimed to be, crossed over to Ireland. But the lad, schooled with evil art by men who were familiar with Edward’s days, very readily replied to all the herald’s questions. In the end (not to make a long story of it), thanks to the false instructions of his sponsors, he was believed to be Edward’s son by a number of Henry’s emissaries, who were prudent men, and he was so strongly supported that a large number had no hesitation to die for his sake. Now see the sequel. In those days such was the ignorance of even prominent men, such was their blindness (not to mention pride and malice), that the Earl of Lincoln [ — ] had no hesitation in believing. And, inasmuch as he was thought to be a scion of Edward’s stock, the Lady Margaret, formerly the consort of Charles, the most recent Duke of Burgundy, wrote him a letter of summons. By stealth he quickly made his way to her, with only a few men party to such a great act of treason. To explain the thing briefly with a few words, the Irish and the northern Englishmen were provoked to this uprising by the aid and advice of the aforementioned woman. Therefore, having assembled an expedition of both Germans and Irishmen, always aided by the said Lady, they soon crossed over to England, and landed on its northern shore.2

There are several interesting points to note in André’s account, and we shall return to his narrative to consider some of the issues that arise later. However, the first key point to notice is that André believed the Dublin King to be an impostor. Of course, this was a natural viewpoint for an employee of Henry VII. It would be astonishing if André – or anyone else writing from the official point of view of the Tudor king and his regime – were to tell us that the Dublin King was a genuine royal personage. We need to keep that fact in mind later, when reviewing the accounts of other historians of the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII.

The second point is that André states that one of Henry VII’s heralds journeyed to Ireland on the king’s behalf and interviewed the pretender. Although this herald clearly expected to be able to expose without any difficulty the boy’s imposture, it is also evident, from André’s report of what took place, that in actual fact, on meeting the pretender, the herald did not find himself in quite the straightforward situation which he had anticipated. His questions were apparently answered without hesitation, and it seems that, in the end, the herald may have concluded that the boy might indeed be the person he claimed to be. Indeed, André states quite clearly the interesting fact that the Dublin King ‘was believed to be Edward’s son by a number of Henry’s emissaries’ even though they were ‘prudent men’.

The name of the herald who made this trip to Ireland on Henry VII’s behalf is left blank in André’s account, which suggests that André’s report is probably at second hand, and that he had not spoken to the herald directly. However, Henry VII’s Garter King of Arms (who had also previously served both Edward IV and Richard III), was John Wrythe (Writhe), who held this post from 1478 until 1504. It seems likely that Wrythe, who had been close to the Yorkist court, and who would have been in a good position to identify a surviving Yorkist prince – or disprove the pretentions of an impostor – may well have been the herald who visited the Irish court of the Dublin King. He is known to have made at least one visit to Ireland.3 If John Wrythe was the herald in question, that might help to explain why André did not interview him in person. At the time when André was writing his account, Wrythe may already have been dead (for he died in 1504). If he was still alive, he was certainly an old man, and probably in a poor state of health. However, it is clear from André’s account that the herald apparently found his mission a less simple matter than he had anticipated. Further evidence on the identity of the Dublin King, taken directly from the contemporary Heralds’ Memoir 1486–1490, will be examined later (see Chapter 5).

As for the nature of the claims made by the Dublin King, André states quite specifically and unequivocally that he was a young impostor, who was attempting to pass himself off as one of the sons of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Two sons of this couple outlived their father. They are often known, both to historians and to the general public, as ‘the princes in the Tower’. However, since by June 1483 they were officially no longer princes; since it is not certain how long they spent in the Tower of London, and since for the purposes of this study it is very important to stress that the two individual brothers experienced two quite separate and very different life histories, use of that popular collective term will, as far as possible, be avoided here.

The two boys in question were Edward (who was Prince of Wales until 1483, and then briefly ‘King Edward V’), and his younger brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York and Norfolk. André claims that both sons had suffered what he characterises as a ‘dire death’ at some time prior to (but not long before) 1486–87. However it is also his contention that the Dublin King put forward a false claim that he was the younger of these two sons of Edward IV, namely Richard, Duke of York. If André was correct in his assertion, we should hopefully be able to find further near-contemporary accounts which tell us the same story. Moreover, we should also be able to find evidence that the boy-king in Dublin used the royal name of Richard.

For the moment it will suffice to say that Polydore Vergil does confirm André to the extent of stating that, initially at any rate, the Dublin King claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury. Moreover, there are certainly Irish coins in existence bearing the royal name of Richard which could possibly date from about this period. Unfortunately, however, fifteenth-century coins do not bear any date of issue. In the present case, this makes their significance somewhat difficult to interpret correctly. The Irish Richard coins could simply date from the reign of Richard III. We shall return to both these points to examine the relevant evidence in greater detail in due course.

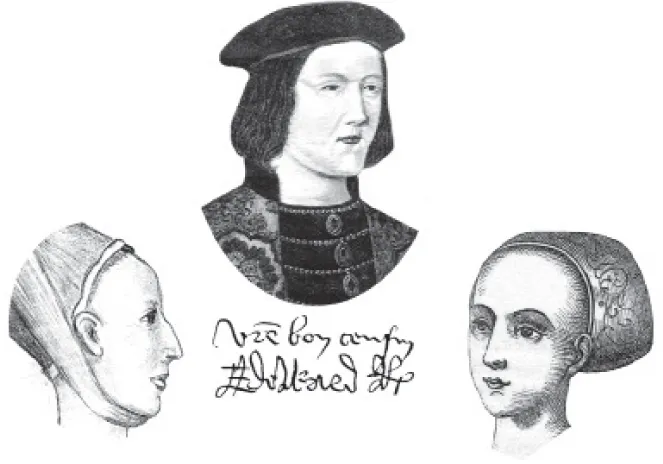

The first Yorkist king, Edward IV, with his two wives: Eleanor Talbot and Elizabeth Woodville. Edward and Elizabeth are the first possible parents of the Dublin King.

First, however, if this hostile historian of Henry VII is correct when he tells us that the Dublin King claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, it follows that in the eyes of historians from a non-Tudor background, the boy might conceivably have been seen as telling the truth. We therefore need to begin by examining the life history of the young Richard of Shrewsbury in so far as that is known. The clear evidence of his life story comes to an end in 1483. However, we shall also have to confront the very complex evidence of what became of him after 1483, and the question of when, where and how he died.

As his toponym indicates, Richard was born in Shrewsbury on 14 August 1473, the second son of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. The reign of the Yorkist dynasty, which had first formally claimed the throne in the person of Richard of Cambridge, Duke of York, had finally been made a reality by that duke’s eldest son, Edward IV, in 1461. The Yorkist claim was founded upon the principle of legitimacy, which arguably gave the princes of York a better right to the English crown than their Lancastrian cousins. As we have seen, however, it then becomes difficult to establish whom Edward IV married.4

It appears to be the case that Edward IV contracted two secret marriages. The first of these, which probably took place in June 1461, was with Eleanor Talbot (Lady Butler), daughter of the first Earl of Shrewsbury. The second, reportedly in May 1464, was with Elizabeth Woodville (Lady Grey). The first union was childless, but its enduring consequence was that it made the second union bigamous, because the two marriages overlapped. As a result, the children born to Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville were all technically illegitimate – and hence were ultimately excluded from succession to the throne. These, at any rate, were the conclusions reached by the Three Estates of the Realm in 1483, and formally enacted by Parliament in 1484. Thus, ironically, the marital conduct of the first Yorkist king did much to undermine the principle of legitimacy upon which his family’s claim to the throne had been based.

At the time of his birth, however, Edward IV’s son Richard of Shrewsbury was generally assumed to be legitimate, and was seen as the new second in line to the throne – thereby pushing his senior royal uncle, the Duke of Clarence, one step further from the prospect of ever wearing the crown of England. Richard was created Duke of York on 28 May 1474, when he was less than 1 year old, and he was knighted just under a year later, at which time land formerly held by the Welles and Willoughby families was settled upon him. In May 1475 both Richard and his brother, Edward, were made knights of the Garter.

The death of John Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk, in January 1475/76,5 offered Richard’s parents an unexpected further opportunity to improve their second son’s future. Plans were made to marry him to Norfolk’s only living child, his daughter, Anne Mowbray (1472–81), who, incidentally, was also the niece of Eleanor Talbot. A papal dispensation was required for the marriage of Richard and Anne, because they were close relatives through their mutual Neville ancestry.

Richard’s marriage to Anne was celebrated with great splendour in January 1477/78, at the Palace of Westminster. On Wednesday, 14 January 1477/78, the 5-year-old bride, accompanied by the king’s brother-in-law, Earl Rivers, was escorted into the king’s great chamber in the Palace of Westminster, where she dined in state in the presence of a large assembly of the nobility and gentry of the realm.6 The following morning Anne was prepared for her royal wedding ceremony in the queen’s chamber, from which she was escorted by the queen’s brother, Earl Rivers, on her left. At her right hand side was the king’s nephew, the Earl of Lincoln. Her procession passed through the king’s chamber and the White Hall to St Stephen’s Chapel, the site of which is occupied today by the House of Commons. This Chapel Royal, brightly painted and gilded more than a century earlier by King Edward III, was also adorned for the occasion with rich hangings of royal blue, powdered with golden fleurs de lis.

In St Stephen’s Chapel, under a canopy of cloth of gold, the royal family was assembled to await Anne. The king and queen were there, with both their sons – possibly one of the rare occasions on which the two princes found themselves in the same place at the same time. Their sisters, Elizabeth, Mary and Cecily of York, were also present. So was their grandmother – Anne Mowbray’s great-great-aunt – Cecily, Duchess of York, mother of the king, and the ‘queen of right’, as she was called.

Anne’s local Ordinary, Bishop Goldwell of Norwich, richly vested in a cope, waited at the chapel door to receive the bride. However, her procession was halted by Dr Coke, who ceremonially objected to the marriage on the grounds that the couple were too closely related, and said that the ceremony should not proceed without a dispensation from the pope. Dr Gunthorpe, the Dean of the Chapel Royal, then triumphantly produced and read the papal dispensation.

Once it had thus been formally established that the Church permitted the marriage contract, the Bishop of Norwich le...