- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

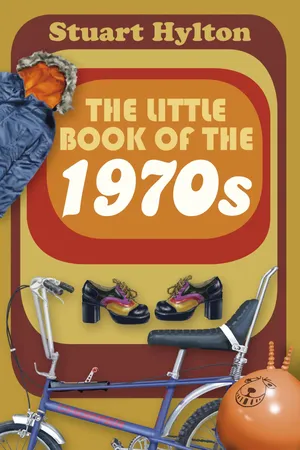

The Little Book of the 1970s

About this book

The Little Book of the 1970s is a fast-paced and entertaining account of life in Britain during an extraordinary decade, as we moved from the swinging sixties to the punk-rock seventies. Here are dramas, tragedies, scandals and characters galore, all packaged in an easily readable 'dip-in' format. Witness how major national and international events impacted on the population at home, the progress made by technology and the fads and fancies of fashion and novelty. Those who lived through the decade (and are therefore experts on the subject) should find plenty to remind, surprise, amuse and inform them, while a younger generation will see how different the world of the 1970s was to the one that we inhabit today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Little Book of the 1970s by Stuart Hylton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

As Seen on TV

Mass television ownership had been established by the 1970s. Nine out of ten of the population described viewing as a major leisure activity. But with only three channels to choose from, no video recordings and with computer games in their infancy, people were much more likely to be watching the same programmes. Thus they became part of the cement that bound the nation together, with shows like the Morecambe and Wise Christmas specials attracting audiences of well over 20 million.

The seventies were the decade of colour television. It first became available in 1967 but by 1970 only 1.7 per cent of the population had one. Colour started outselling black and white in 1974 and by the end of the decade there were over 11 million colour sets out there; only three out of ten households were still watching in monochrome. Many of those early sets were rented, since they were very expensive to buy (up to £400, or several thousands in today’s money).

To begin at the beginning, what were the tiny – and not so tiny – tots watching in the 1970s?

When We Were Very Young

Captain Pugwash first appeared in black and white in the 1950s, but the colour television series ran between 1974 and 1975. It told of the adventures of Captain Horatio Pugwash and the crew of the Flying Pig. They were incompetent pirates who were constantly getting into scrapes, often involving their arch-rival, Cut-Throat Jake of the Flying Dustbin. More often than not Tom the Cabin Boy, the one member of the crew who had his wits about him, would get them out of trouble.

One of the series’ lasting claims to fame is the urban myth that the programme had characters with sexually explicit names – Roger the Cabin Boy, Seaman Staines and Master Bates. This story is thought to have originated in 1970s rag magazines, but when in 1991 the Guardian and the Sunday Correspondent reproduced it as if it were fact, John Ryan, the creator of the programme, successfully sued them.

What actually was crude about it was the animation of the series, which was done by cardboard cut-outs of the characters or other bits of the scenery being slipped in and out of shot in real time. Speech was animated by moving a piece of cardboard in front of the characters’ open mouths. The animation was almost as primitive on Ivor the Engine, except that they used stop-frame techniques to move the cardboard cut-outs. The series was produced by Oliver Postgate, and was filmed in a cowshed at his home. It tells the story of Ivor, a small green steam engine who operates on a rural railway in the ‘top left-hand corner of Wales’. His driver, nominally, is ‘Jones the Steam’ – except that Ivor, being a very wilful little engine, can travel under his own steam without human assistance, can speak, and is strongly inclined to break railway regulations. His lack of respect for the rules gets him into trouble with Dai Station, the station master, who is a stickler for them.

Ivor even sings in the Grumbly and District Choral Society, having had his whistle replaced by three organ pipes for the purpose. If you think it odd for a railway engine to be in a choir, one of the choir’s other members for a time was Idris, the red Welsh dragon. The nation’s heritage railways naturally cottoned onto Ivor. A small industrial locomotive was given a makeover to look more like Ivor and went on to make personal appearances around the country.

Stop-frame animation also featured in the series Bagpuss, produced in 1974 by Peter Firmin and Oliver Postgate. Only thirteen episodes were ever made, but in 1999 it won a BBC poll for the favourite children’s programme and in 2001 even managed to come fourth in a poll organised by the rival Channel 4. It is set in a shop (more particularly in a shop window) in late Victorian times. The shop is run by a little girl called Emily, who does not actually sell anything, but displays broken and lost objects for their owners to collect and repair. The first part of the story is told in sepia photographs, as Emily shows her latest found object to Bagpuss, a knitted stuffed cat who lives in the shop window. When Emily departs, Bagpuss and the other characters in the shop window come to life, and sepia photographs give way to stop-frame animation. The characters discuss the new object, then repair it for the owner to collect.

Very few programmes for small children have a character based on the philosopher Bertrand Russell, but Bagpuss had Professor Yaffle, played by a woodpecker bookend (an imaginative if obscure piece of casting). This clearly impressed the University of Kent, for in 1999 they awarded honorary degrees to Firmin and Postgate. The two nominees said the award was really for Bagpuss, who was subsequently to be seen in academic dress.

If Bagpuss has a Bertrand Russell character, at least The Wombles have a large library of books left behind by human visitors to their home, Wimbledon Common. They also have a leader, Uncle Bulgaria, who is an avid reader of The Times (and thus, by definition, almost an intellectual). The Wombles have their origin in a series of children’s novels, written by Elizabeth Beresford and published from 1968. They concern a race of pointed-nose furry creatures who live underground (they are everywhere, but the stories centre on those beneath Wimbledon Common).

The books turned into a children’s television series, first shown between 1973 and 1975, a series of novelty records, a feature-length film in 1977 and even a rude football chant based on a Wombles record (‘Underground, overground, wandering free, the w*****s of Manchester City are we’). But unlike many football fans, the Wombles are useful members of society. They spend their time collecting and recycling the rubbish humans leave behind. Understandably, they have a pretty low opinion of humanity (with some exceptions, such as the Royal Family – you never see Her Majesty throwing away her McDonald’s wrappings). That is why they keep well hidden from us. The name ‘wombles’ comes from a mispronunciation of ‘Wimbledon’ by one of the author’s children.

Speaking of mispronunciations, what is the link between the children’s programme The Magic Roundabout and one of the most famous French presidents? The television programme was originally French and there was a conspiracy theory in that country that it was in some way a satire of French politics. When it was remade in Britain, the central character was renamed Dougal and those same conspiracy theorists assumed that it was a none-too-subtle anglicising of the name de Gaulle.

The French series proved difficult to dub into English (particularly since the perfidious French neglected to supply the scripts along with the visuals). The BBC therefore redubbed it, using scripts written and performed by Eric Thompson (Emma’s father) which bore precious little resemblance to the originals. It went out in 441 five-minute episodes between 1965 and 1977 (in colour from 1970), drew audiences of up to 8 million and attracted a fanatically devoted following. One theory is that at least part of the adult (or more precisely, student) audience watched it while stoned and saw psychedelic implications in it that the rest of us missed.

It was a puppet show, set in a magic garden, and used stop-frame animation and a cast of colourful characters. In addition to Dougal (a grumpy terrier), they included Zebedee (a jack-in-the-box), Brian (a well-meaning but simple snail), Ermintrude (a matronly cow), Dylan (a hippy rabbit) and Florence (a young girl). The show generally used to close with Zebedee saying ‘Time for bed’, which, given that the show went out before the six o’clock news, was far too early a bedtime for any viewers other than the stoned students.

Tiswas and Swap Shop

Tiswas started life on ITV in 1974 as a series of links between filler programmes such as cartoons, but soon proved more popular than the programmes it was linking and became a Saturday morning children’s programme in its own right. Hosted between 1974 and 1981 by Chris Tarrant, it also became a vehicle for Lenny Henry, Jim Davidson, John Gorman (formerly of The Scaffold group), Jasper Carrott and ventriloquist Bob Carolgees and his punk dog puppet Spit. It consisted of a mixture of film clips, pop promos and general insanity, with the audience being doused in water and anyone, including the cameramen, liable to catch a flan in the face. This latter was felt by management to set a bad example, and was nearly banned. Testament to its popularity with an adult (or, at least, fully grown) audience came from the successful tour the programme did of the university campuses.

The BBC recognised the popularity of its rival and in 1976 brought in Rosemary Gill of its Blue Peter team to revitalise its Saturday morning broadcasts. The result was The Multi-coloured Swap Shop (or just Swap Shop for short). Running from 1976 to 1982, it was presented by Noel Edmonds, with help from Keith Chegwin, Maggie Philbin and, adding a much-needed bit of gravitas, John Craven as its news and current (children’s) affairs correspondent.

The central feature of the programme (which otherwise was a familiar round of music, celebrity appearances, competitions and cartoons) was the ‘swaporama’. In this, a BBC outside broadcast unit would go to some sporting venue and children (on occasions, up to 2,000 of them) would turn up to swap their belongings. The venue would be one the BBC were going to cover for a sporting event that day in any case, making the cost of the OB team sustainable. Many other television favourites cut their teeth on the programme, including Philip Schofield, Sarah Greene, Mike Read and Andi Peters, not to mention the likes of Michael Crawford and Delia Smith, who was on hand to show the viewers how to make sausage rolls. Among its more bizarre participants were a stuffed toy dinosaur named ‘Posh Paws’ (almost Swap Shop spelt backwards) and someone called Eric, who lived among the studio rafters and used to lower the viewers’ postcards down to the presenters in a plastic ball.

Swap Shop was apparently voted the most influential show ever by industry insiders in 1999. But its competition with its ITV rival even spread to the football terraces, with supporters chanting out the names of one or other of the shows against each other.

Magpie

The BBC’s venerable flagship children’s programme Blue Peter has been broadcast since medieval times (actually 1958). It was always very worthy, but rather dull and square – a bit like having your dad making a television programme for you as children (perhaps they could have called it Blue Pater?). But between 1968 and 1980 it had a commercial television rival – Magpie. This set out to be as worthy as the original (well, almost as worthy) but a bit more groovy. Instead of the likes of Peter Purves and John Noakes, its presenters included a former Radio 1 disc jockey, Pete Brady, and ex-Bond girl Jenny Hanley. It even had a genuine rock band (the Spencer Davis Group under an assumed name) to perform its signature tune. At its peak the show pulled in audience figures of 10 million.

One of the characteristics of a magpie is that it has a reputation as a thief, and one explanation of the show’s name is that it completely stole the format of its competition. Certainly, the newcomer copied many of the features of the established BBC model. Its content included items on news, science and history, but it was leavened with more on pop music and fashion. It, too, had collections for good causes, but rather than collecting postage stamps and milk bottle tops, they relieved their viewers of their (or, more likely, their parents’) hard-earned cash. Blue Peter had a steam engine named after it, so Magpie had to do the same (number 44806, now living under an assumed name on the Llangollen Railway). Blue Peter had pet dogs, and Magpie had as its mascot a pet magpie named Murgatroyd.

The competition between them could sometimes get heartfelt. Blue Peter was scripted, whereas the Magpie presenters were free to improvise. Blue Peter doyen Biddy Baxter said of their rival, ‘they used to make the presenters arse around in a way that children found extremely embarrassing, and it was just a terrible mess’. One of the Magpie team responded that if their show was messy, then Blue Peter was just sterile. No reason was ever given for Magpie’s disappearance in 1980, though there are dark rumours of some unspecified ‘boardroom politics’ being involved.

When We Were Very Silly

So what were the grown-ups of the 1970s watching (at least, once The Magic Roundabout and Tiswas had finished?). The decade’s viewers had mixed fortunes. Starting with comedy, on the one hand there was Terry and June, a domestic sitcom that took blandness to a new level. Terry Scott and June Whitfield played a middle-class, middle-aged suburban couple coping with everyday tribulations (in his case, often self-inflicted). It started life in 1974 as Happily Ever After. Following a change of writers in 1979, virtually nothing else changed but the name, and that for contractual reasons. The ‘new’ programme continued until 1987, despite its dismissal by the critics, and managed to achieve better viewing figures than the edgier alternative comedy shows, some of which lampooned it. The programme’s apologists (they do exist) maintain that Scott is everyman and that male viewers in particular are seeing their lives played out in a comedic version, as wife, employer, life and even inanimate objects conspire against him.

Other equally gentle, but perhaps more highly regarded and durable comedies of the period include Last of the Summer Wine, following the antics of a group of Yorkshire pensioners and Dad’s Army, following the antics of a group of Walmington-on-Sea Home Guard pensioners during the Second World War. But the decade also gave us one of the enduring classics of television comedy, Fawlty Towers (1975–79). These complex farces were faultlessly constructed and the characters superbly drawn and played; the dialogue crackles and there are memorable one-liners. Only twelve episodes were ever made.

The series is set in a Torquay hotel and based on a real-life character – apparently an unbelievably rude and snobbish man called Donald Sinclair (who John Cleese says was much worse than Basil Fawlty – apparently the staff used to lock him in his room to stop him annoying the guests). The Monty Python team stayed at his establishment and suffered at his hands, leading John Cleese (and his then wife and co-writer of the scripts, Connie Booth) to revisit the hotel and study him further. The result is Basil Fawlty, a hotel proprietor who is unbearable towards the guests, hopelessly henpecked by his wife (played by Prunella Scales) and frequently on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The character was given a trial run in a 1971 episode of Doctor at Large but the series itself nearly did not get made. The BBC executive who was shown the first script said of it, ‘This is full of clichéd situations and stereotypical characters and I cannot see it as being anything other than a disaster.’

Even Bill Cotton, the Head of Light Entertainment, could see nothing funny in the script he was shown, and it was only the fact that he trusted Cleese that made it possible for the show to go ahead. Most inexplicably of all, even the critics did not get the joke at first, having seen the televi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Introduction and Acknowledgements

- Contents

- 1 As Seen on TV

- 2 Sequins and Safety Pins: 1970s Music

- 3 A Decade of Disasters

- 4 Naughty Boys

- 5 Gone But not Forgotten

- 6 Power to the People

- 7 Child’s Play: 1970s Toys

- 8 Sporting Heroes and Zeros

- 9 Two Prime Ministers

- 10 British Leyland

- 11 Conspiracy!

- 12 Rupert Bare: The Oz Trial

- 13 And Another Thing …

- Copyright