![]()

1

MOBILISING THE CITY

Birmingham at the outbreak of war was a leading city of the British Empire, where huge wealth and opportunity sat side by side with extreme poverty and hardship. It had grown dramatically from the small town of the eighteenth century to a manufacturing and industrial powerhouse, and the major employers – Cadbury, Dunlop, Nettlefold and Austin – employed thousands of workers. Granted city status in 1889, it was then expanded considerably by the Greater Birmingham Act of 1911 which almost trebled the city’s geographical area and brought Aston Manor, Erdington, Handsworth, Yardley and most of King’s Norton and Northfield within the city boundary. A month before war was declared, on 2 July 1914, the city’s best-known politician and elder statesman, Joseph Chamberlain, died and was buried at Key Hill Cemetery.

Even before the war began, the impact of European uncertainty was felt in Birmingham. The end of July and first few days of August 1914 saw a significant rise in the cost of living as food prices rocketed. On Saturday, 31 July the price of butter, bacon and sugar went up alarmingly.1 A few days later the local press reported a run on food shops and many closed their premises.2 By the end of the first week of war, the price of sugar had increased from two and a half pence a pound to between five and six pence, and bacon from between ten pence and one shilling per pound to over a shilling and two pence a pound. Some of the immediate wartime measures made the situation worse, the military requisitioning of forty-five of the Co-operative Society’s horses, for example, meant that routine food deliveries were impossible.

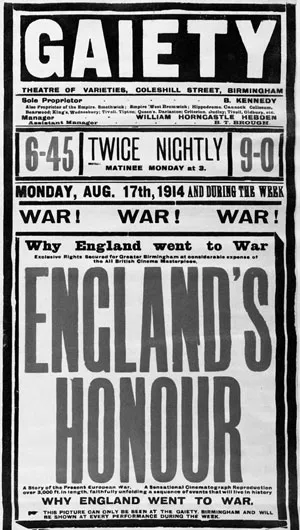

Playbill from the Gaiety Theatre advertising a war news film, August 1914. (Theatre Playbills Collection)

The hike in prices was accompanied by a depression in trade. Contracts and orders were cancelled or put on hold due to uncertainty about the situation. Countless people were made unemployed or put on short time which dramatically affected their pay. Firms such as Tangye, Metropolitan Waggon Works and many of the jewellery firms made drastic reductions to the working week, down to half time in many cases. William Henry Norton worked in the stores department at Veritys Plume and Victoria Works in Aston. On 7 August he received a letter from the firm:

Owing to the war … an immediate reduction in expenses is necessitated. Able-bodied unmarried men will not be required, as such can go to the Front and fight for their Country and homes, while the services of most of the lady members of the staff will be dispensed with temporarily; others will be put on reduced pay. In your case your salary will be reduced by 50% as from Monday, August 17th. If the war continues further reductions may be necessary.3

The local labour exchange dealt with double the normal rates of unemployment. In July 1914 there were 2,600 men and 600 women registered as unemployed. By the end of August this had increased to 6,200 men and 1,700 women. Male unemployment reduced during September and there were fewer than 4,000 men registered by the end of the month. In contrast the number of unemployed women increased to 1,766. Although the problems were short term and industry and employment would see a recovery very soon, there is no doubt that it caused significant hardship, particularly to the poorest who had no savings on which to fall back and so had to turn to charities for help. The records of the children’s charity Middlemore Emigration Homes illustrate how the outbreak of the war affected the poorest, and those whose circumstances as single or widowed parents exacerbated their difficulties. On 28 September, George Ball, a single father who worked at Brotherton & Co. in Nechells, turned to Middlemore for help when he could no longer maintain his child on his own. His earnings – twenty-two shillings a week when in full-time employment – had decreased substantially and he was in considerable debt. Similarly, in November, Ellen Elsmore – a single mother and hand-press worker – reported that her weekly earnings were normally between nine and twelve shillings but for the previous several weeks she had been paid only seven shillings a week and, as her rent alone was three and six, she had fallen into arrears.4

Great hardship was also caused in the early weeks of the war by the failure of the army to pay the separation allowance (a financial support due to the wives and dependants of soldiers who had enlisted) on time. Local schools reported an immediate effect on children in the poorer parts of the city as families who had lost a wage earner struggled to make ends meet. On 24 August 1914, Mr Tipper, the head teacher of Dartmouth Street School, recorded in his logbook that ‘Owing to the War there is much distress in this district. About 40 fathers and 60 brothers of our boys have been called up. The number of Free Brk. [breakfast] Cases has risen from 30 to 70. Next week will see it doubled.’ The numbers peaked on 25 September, when 300 boys were receiving free breakfasts at school. By mid-October the separation payments were beginning to come through and the hardship cases decreased accordingly.5

The initial distress caused by the war was so intense that a meeting of social welfare workers from across the city was called at the instigation of the acting lord mayor, Alderman Bowater, on 7 August. They formed the Birmingham Citizens’ Committee, which brought together the existing charitable provision of the City Aid Society and the Birmingham branch of the Charity Organisation Society. The Citizens’ Committee’s function was to relieve distress and administer national relief funds such as the Prince of Wales’ Fund. Bowater also launched a public appeal to raise money. The Citizens’ Committee comprised of a central committee based at the Council House and forty-one district committees across the city. It made temporary grants to those in need of relief and assisted with managing unemployment through a scheme for transferring people who had been thrown out of work in one trade to another where there was a labour shortage. Women, who formed a substantial part of the unemployed, were transferred from occupations such as dressmaking, tailoring, the cycle trade and pen-making into munitions and other war-related work. As government war contracts began to come through the situation improved; by the end of March 1915 there were only 249 cases of unemployment on the books.

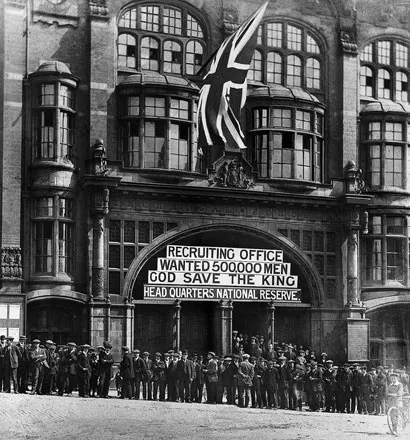

Recruiting Office at the Municipal Technical School, c. 1914. (MS 4616/1)

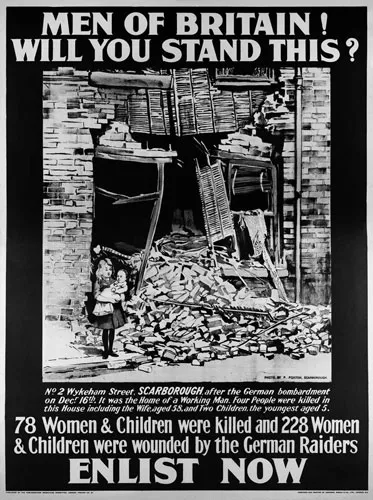

Recruitment poster showing the destruction wrought by the naval bombardment of Scarborough in December 1914. (MS 4383)

BIRMINGHAM CITY BATTALIONS

On 28 August the Birmingham Post appealed to Birmingham men to enlist under the heading ‘To Arms’, and advocated raising a battalion that would be directly connected to the city. On the 29th, Alderman W.H. Bowater, the acting lord mayor, sent a telegram to the War Office offering to raise and equip a City of Birmingham Battalion, on the same principles as the ‘pals’ battalions already formed in Liverpool and Manchester. His offer was accepted. On the same day the Post carried an advertisement – ‘A “City” Brigade. Who Will Join? An Appeal for Names’ – which requested 1,000 men to come forward by the end of the week. The call was answered eagerly and the Post compiled a pre-recruitment list of volunteers which it published over the following days. By the evening of Saturday, 5 September, 4,500 names had been received. A special recruiting office was opened in the Art Gallery Extension and actual recruitment began on 7 September. The required number for the first battalion was reached within a week, and from 14 September enrolling began for a second battalion. Three City Battalions were recruited in total. Money was raised by public subscription from individuals, local firms and organisations to provide the three battalions with equipment. The men departed for their training, the first two City Battalions to Sutton Park and the third to Springfield College, Moseley, with an overflow of men billeted in local houses. Until their uniforms arrived they were dressed in civilian clothing, with a badge in their buttonhole to mark them out as City Battalion recruits. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd City Battalions were later officially known the 14th, 15th and 16th Service Battalions of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Church Parade, Birmingham City Battalion in Corporation Street, 1915. (MS 2724/2/B/3730)

Even when the army separation allowances were being paid, there were still cases where the family could not make ends meet and the Citizens’ Committee became the local body responsible for the care and relief of dependants of soldiers and sailors. It could give supplementary grants for rent, sickness or in special emergencies. It could provide a maternity grant to poor mothers for four weeks before the birth and three weeks afterwards. It made grants to elderly parents who had lost the wages of one or more sons as well as to wives and children, and it could assist when soldiers returned home wounded. Widows were given help to fill official forms and correspond with official bodies, and the committee later also administered the War Pensions Act locally.6 Like many charitable concerns, the committee’s assistance went hand in hand with moral regulation of the behaviour of those in receipt of their help. The guide that they produced for their social workers indicates that they took a dim view of what they perceived as ‘abuse of grants’, particularly through ‘drunkenness or shirking of work by husband in unemployment cases’. Unmarried mothers were also suspect and could not receive the army separation allowance, although the Citizens’ Comm...