![]()

1943

‘I am bursting with pride’

In July 1942, General Montgomery had taken over from Auchinleck and the tide began to turn. The Anglo-American First Army had landed in North Africa in November 1942 (Operation Torch), and met up with Montgomery’s Eighth Army in Tunisia, finally capturing Tunis on 10 May. The three-year battle for the Western Desert and North Africa was finally won. This paved the way for the Second Front that Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed in January 1943 in Casablanca: an attack on Europe through Italy, perceived to be its soft underbelly, leading to an unconditional surrender.

As a result the focus of the war shifted back to Europe, and Sheila was sent from Alexandria to Cairo to help Admiral Ramsay and his team plan Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, the precursor to landing in Italy itself. She was assigned to the important work of monitoring, via cyphers and signals, both enemy and British fleets in the Mediterranean. The work she did with Ramsay remained her proudest achievement and she was rewarded with the coveted ‘second stripe’.

When looking through her papers, I found a letter she sent to The Times on the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day, singing the admiral’s praises, which elicited a response from his son, David Ramsay. In her reply she says:

For myself, I knew little about your father when I was plucked from the C-in-C’s cypher office in Alex to join his staff at Cairo, save that he masterminded the evacuation of Dunkirk. Only 22, I was to be in charge of the speedy circulation of signals which came up from Alex each day … we were a motley crew to join the cream of Navy in a dusty old house in the backstreets of the road to the Pyramids, crammed into a tiny room with nothing but functional furniture – no detailed maps on the walls, and wastepaper baskets which had to cleared and the contents burned only by responsible personnel … security was minimal, although first class. No Wren in those days ever signed the Official Secrets Act, Egypt was bursting with spies, and we all lived ashore in various YWCAs in the city. It goes without saying that we were entirely trusted.

As for the Admiral, his calm and friendly manner belied the importance of the task he was undertaking. He had time to entertain even most junior officers such as me, and I was enormously impressed to hear from a Wren friend who had been on his staff at Dover in the days of Dunkirk that he had recognised her walking down the street in Cairo and had stopped to greet her by name.

It may seem strange to you, but in after years when faced with problems of integrity it was the memory of your father’s example which guided me to stick to my guns.

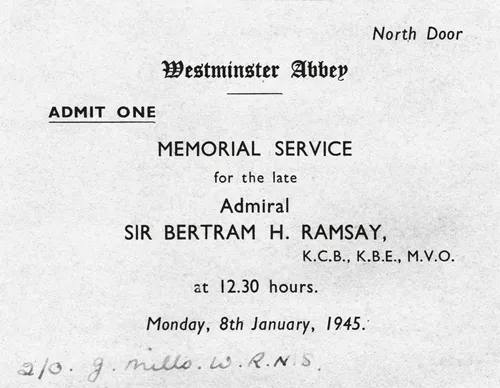

Her scrapbooks contain an admission ticket and a copy of the memorial sheet from his service in Westminster Abbey (he was killed in a plane crash in France in 1945, not long after the D-Day landings, when he was Naval Commander-in-Chief). She writes vehemently in his defence to her mother, who must have been critical of him.

While the letters reveal a seemingly never-ending social whirl of dining, dancing, sightseeing, yachting, the races, all jockeying for position with her hobbies of singing and riding, there are frequent mentions of the long hours and the rigours of office life – including an obsession with hair length – and her desperation to rejoin the war on a more active front after the thrill of working with Admiral Ramsay on the invasion of Sicily. As she herself says, ‘Our shadow is diminishing instead of increasing. Soon I feel we will fade out altogether and then what?’

Admission ticket to Admiral Ramsay’s memorial service.

Cairo in the middle of the war was a vibrant place, despite all the political upheavals of the time and a profound anti-British sentiment felt by some sectors of Egyptian society. Things were not only expensive for the forces (Sheila complains about the price of various necessities), but for the poor fellahin, or peasant, the wartime inflation and shortages of cereals, sugar and paraffin represented an enormous hardship. Anti-British propaganda – for Cairo was a hotbed of spies – would have fuelled such feelings; and with the king openly at loggerheads with the British ambassador, as well as with his own Prime Minster, the state of Egypt was far from calm.

Nevertheless for the officers, whether stationed in Cairo or when on leave, life was to be enjoyed at all costs. The military working day began at 9 a.m. and then broke for lunch at 1 p.m., when one retired to either the Gezira or Turf Club to swim and play tennis, with lunch being a sumptuous buffet. Then back to work from 4 p.m. until 9 p.m., when it was out to a restaurant followed by dancing. Other ranks were not admitted to the clubs, nor to the more upmarket nightclubs, such as the Continental and Shepheards, where Sheila danced the night away with her beaux. Groppi’s, on the other hand, was open to all, but was prohibitively expensive. This is where old Cairo society met for gossip and coffee on a daily basis.

The ratio of women to men meant that women were, according to Artemis Cooper, a ‘privileged minority’. She continues, ‘it was open season for husband hunting … young women in Cairo knew they would never have such choice again, certainly not in post-war Britain … the war provided not only the first real romantic opportunity for these young women, but also the most powerful argument for giving in to male supplication. That the man in question might be killed next week lent not only a poignant intensity but also a noble, generous element to the affair.’

In 1943, Sheila is tiring of the endless rows with John Pritty, although I imagine she felt torn, as he must have endured privations in the desert, weeks on end in terrible conditions – either stranded by sandstorms, or bogged down in mud (yes, mud) depending on the season – and mindful of the extremely high casualty levels suffered at the front due to the Germans’ superior air power, tanks and guns.

She has all this time retained a friendship with Robin Chater, whom she met on the boat coming out and, now in Cairo, meets a much more stable suitor in the form of Bruce Booth-Mason, a major in the Indian Cavalry, although he, too, is also drafted to the Eighth Army. She still writes fondly of her ‘childhood’ sweetheart, Paul, and of Jaap, her dashing Dutch officer, whom she met in Scotland. I suspect it was a case of rather hedging one’s bets, as the chances were that one or more boyfriends would not survive.

I only discovered the answer to the obvious question of whether she slept with any or all of her boyfriends when I, quite by chance, found a bundle of love letters from my father to her, written in 1946, during their engagement. Despite Olivia Manning’s loose living or, as my mother would have said, ‘fast’ ladies in The Levant Trilogy, the rule seemed to be that ratings did, while officers didn’t! I will return to these letters in a later chapter.

❖❖❖

The New Year gets off to a rocky start with a row with John Pritty, her current boyfriend:

C in C Mediterranean

10/1/43

My dear Ma and Pa –

First, a happy New Year, second, thank you for your cables, letters, pc’s and aircards which have just started coming in again. I’ve had no airmail letters, tho’, since the beginning of December, and fear they may be lost. I do hope not.

Well, I wrote and told you of my Christmas so now of my new year. New Years Eve and I had to spend on duty unfortunately, but Audrey Dean (a new girl and so nice) and I danced round singing Auld Lang Syne, and we drank to the New Year in ginger beer and munched bananas! Then the next day (New Year Day) I had 3 days leave and went up to Cairo. I had arranged it all beautifully, to fit in with John coming out of hospital, but he suddenly took umbrage and we only met once. However, I stayed with Ann Halliday at the YWCA and was determined to enjoy myself. So on my 2nd day, 3 of us took a gharry and went to the Musky, which is the native market and bazaar. There you really see Egypt as it has been for thousands of years. Narrow narrow streets with little shops open to the street, and inside men and boys sorting cotton, beating copper into pans, making minute and intricate silver bracelets in filigree. It’s full of shrieking children, beggars, guides, merchants and people buying. We suddenly found ourselves by the Blue Mosque which is a place I’ve wanted to visit for ages. It’s the oldest mosque in Cairo and is 900 years old. We went inside and soon found an awfully nice little man who became our guide. It was small, really, inside, with very high ceilings and a dome 40 or 60 feet high. Pillars of granite and marble which had been brought by goat from Aswan, taking 3 months. The tops of the pillars and the ceilings were inlaid with gold and lapis lazuli, and the windows were filled with the most gorgeous coloured glass you’ve ever seen. In the centre was the tomb of the man who built it, a king from Turkey: this was plain and made of sandalwood, and there was a short pole at the head with a monk showing how tall the king was. Actually, he was a hunchback and therefore very small. Then a fortune teller came along with a little bag of sand which he laid on the floor, drew a circle in the sand, and told our fortunes. Apparently I am destined for 3 children, the 1st being a boy with red hair and green eyes! So! While coming out of the Blue Mosque, an old old man came in in rags, bearing on his back a water bag made from goat carcass. It was just like the Bible. Then we went on to see a very old home, now protected by the Egyptian government, which is the only one of its kind left in Cairo. It is 600 years old, and perfect. You go down a narrow street and through a gate and find yourself in a courtyard with a palm in the middle, and then house all round. There are rooms for reading the Koran during Ramadan, and balconies for the women to sit and listen too. Coffee rooms, with fountains in the middle, and old old carpets on the floor. Bathrooms with hot and cold water and the harem where the Sheikh lived with his 3 wives. Little mosques and large garden behind with vines and orange trees growing and lastly, a water wheel and wheel used for grinding corn. All exactly as they had been 600 years ago. I was just thrilled. There was a dear old boab or ghaffer in charge who had been a sergeant in the last war and who had won a medal. Well, our little guide then took us to a silver factory, where we saw little boys of 5 and 6 making beautiful filigree brooches and bracelets. I bought one which I am sending to Rosemary. I didn’t think you’d wear bracelets, mummy. After drinking coffee with the owner, a young man who was most helpful, we then proceeded on to a silk shop, because the Egyptian brocade is heavenly and I have an evening gown made of it. Well, I bought a glorious bit – a deep royal blue, with gold flowers all down it, and shot so that it shines gold when worn. Already I have given it to the dressmaker and she is making an evening dress for me. By this time we had been exploring for about 2 hours, and really thought we had better go back to lunch, but no, the little man insisted on taking us to the perfume shop which we found in the spice market. The smell here was simply marvellous. Great sacks of cloves, chilies, cinnamon, corn of all kinds were displayed in front of the shops. When we found the perfume shop, the man immediately produced chairs and we proceeded to smell, and have dabbed all over us, all the perfumes of Arabia. It really was most amusing! Ann eventually bought the secret of the desert (!) (it smelt like citronella to me!) and I, Camabon (which I have since lost). Then we really had to go, so having tipped our guide (who was most fair about it) we rushed off to find a tram – which was so full that we had to stand on the step and cling on for dear life! How we all laughed and everyone was so kind to us, gave us seats, told us where to go! I did enjoy it so. I know you would have adored it mummy. I think I’ll do as last time and continue this on another card. I hope they both arrive at the same time …

Well, that afternoon Ann and I decided we would go and visit the Pyramids. Unfortunately we left it rather late but set off on a tram, as usual, it was terribly crowded and we found we had to travel 2nd class as there was no room. It was absolutely packed with fat old women with baskets, people who looked like Bedouins with all their earthly possessions with them. English, Arabs, Greeks – just everyone. Eventually we got out at Giza, and took a taxi. We arrived at the Pyramids at about 4:30 and the sun was almost setting. However, we hurried on, and saw 2 horses which we decided to hire. Here we did strike a patch of unpleasantness as the 2 syces kept saying ‘give me tip now’, but we were firm. We chartered a guide and off we sped. I wasn’t in the least bit disappointed, as most people are, and wanted awfully to climb up and go inside, but there wasn’t time. The sun sets so fast here. So we rode round to the Sphinx which I adored, but I am very annoyed with Napoleon for knocking off his nose. We also saw an old granite temple nearby, and a lot of tombs cut into the rock. Unfortunately it really was growing dark, so we had to turn back. What we want to do next time is to start out early, thoroughly explore the Giza pyramids, and then take horses and ride over to Sakara, where there are some more far older pyramids, tombs of the kings and the ancient city of Memphis. But I’ll have to get more leave before we can do this. It was now quite dark, for we rushed off and caught a tram and landed up in Cairo about 3/4 hr later. The blackout there is negligible, and all the shops were open and ablaze with light. We really were terribly tired by now, and so had dinner and went back to bed.

The next day I had to return to Alex, but I visited Ann’s new office which I liked tremendously, and we had coffee in the famous Groppi’s.

Since I have been back here, John has been staying here on convalescent leave, and eventually, after seeing him around the place, we did meet. The trouble is, in a nutshell, that he wants to become engaged to me now, and I feel it would be a silly thing to do, we have been engaged, on and off, several times now, and at the moment I’m not at all sure how things stand, but he really is so temperamental it rather frightens me. I really feel the best thing to do is to wait till the end of the war and see how we feel. Another thing is that he’s probably leaving this country and going miles away, which wouldn’t entirely help matters would it? Anyway, at the moment, we are the best of friends.

I was told this week by the P.P.O. [Principal Personnel Officer] that he had recommended me for a 2nd stripe but not to bank on it as all promotions have to come from home. Well, I just know that I won’t get it, or really deserve it, in view of the far senior people there are out here, and anyway, feel it must just...