![]()

1

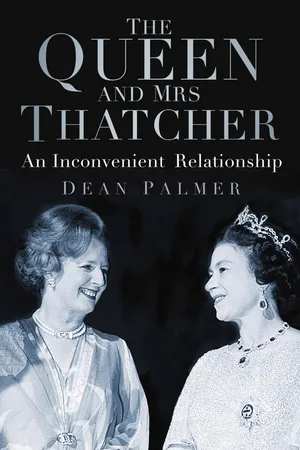

THE IRON LADY AND

THE ENGLISH ROSE

The meetings between the queen and Mrs

Thatcher are dreaded by at least one of them.

Anthony Sampson

At Conservative Central Office in Smith Square on 4 May 1979, Margaret Thatcher waited impatiently with her husband, Denis, her daughter, Carol, and favoured son, Mark, for the royal summons to Buckingham Palace for an audience with the queen. The previous night, Mrs Thatcher had won an astonishing general election victory defeating the rival Labour Party by 339 seats to 269. While she was still in her twenties, she had been told by a fortune teller at a fête in Orpington that she would be ‘great, great as Churchill’.1 Now she was on the verge of formally being offered the job of prime minister by her sovereign, Elizabeth II.

The atmosphere in the room was like the first day of a new school term, buzzing with feelings of anticipation, excitement and nervousness. Staff posed for a photograph, wearing slogan tops that read, ‘I thought on the rocks was a drink until I discovered the Labour Government’.2 Champagne and a giant chocolate cake, hastily baked overnight in the shape of the door to 10 Downing Street, home of Britain’s prime ministers, were served up. Piped in white icing across the top were the words ‘Margaret Thatcher’s Success Story’.3

Margaret would not become prime minister until the Labour incumbent, Jim Callaghan, had tendered his resignation to the monarch. Protocol dictated that Mrs Thatcher would then kiss the regal hand and officially be asked to form a government by the queen. Only at that point would she become Britain’s first female premier. Elected by the people, the job of prime minister remained, in theory at least, in the gift of the queen.

Now, dressed in a royal blue power suit, cream patterned blouse and her hallmark pearl earrings, Mrs Thatcher waited. And waited. Each time the office phone rang the entire family jumped in anticipation. Was it Buckingham Palace this time? Margaret’s biggest fear was that she would bump into the defeated James Callaghan en route to the palace, which she felt would be embarrassing. What if the two cars crossed? What was the etiquette for greeting a defeated political rival?

‘I wouldn’t want him to think I’m rubbing it in,’ she declared.

Denis sensibly reminded her, ‘Buck House has been doing this for years. I imagine they know the form by now.’4

Finally, the phone rang again. Everyone appreciated this must be the official phone call from the palace. Caroline Stephens, Mrs Thatcher’s diary secretary, went to answer it. Everyone else strained their ears, listening.

‘Wrong number,’ she said. Silence fell for five minutes until the phone rang again. Tensions were running high. ‘This is it!’ declared Caroline, and she went through to take the call. Again everyone struggled to hear. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Oh, thank you, would you hold on,’ she came back into the room. ‘Mr Heath would like to offer you his congratulations,’ she whispered.

Margaret sat for a full thirty seconds without moving, then she replied, ‘Would you thank him very much.’

She snubbed him and didn’t take the call. For almost four years he had been her boss in Cabinet. However, Ted Heath, the former Conservative prime minister, had been anything but supportive after Margaret had surprisingly challenged him as the leader of the Conservative Party after the 1974 election defeat, and won. For the rest of his career, he would sit behind her on the backbenches in the House of Commons, the enduring detractor, never quite recovering from the bombshell of being trounced by a mere woman.

Five more minutes passed, and the telephone rang yet again. At long last, holding out the telephone receiver, Caroline announced, ‘Sir Philip Moore from the palace.’

The queen had issued her summons, and Mrs Thatcher leapt into action. ‘Right. We’re off,’ she said, jumping to her feet. Her restrained and sensible husband, Denis, pointed out that, with a police escort and no traffic lights they would do endless circuits of the Victoria monument until their scheduled appointment time. Carol chipped in that they might look like kerb-crawlers, which wouldn’t give quite the right impression. For years, Margaret and Denis’s sense of timekeeping had never been in sync. Mr Thatcher always complained that his wife didn’t just want to catch the train, she wanted to be on the platform to welcome it in. Not surprisingly, that day Margaret won the argument, as she had on many other occasions, and their driver virtually had to crawl along the Mall so as not to arrive early.5 It would be the last time she sat in the back of the Leader of the Opposition’s car. Once she left the palace, she stepped into Jim Callaghan’s old vehicle, and he into hers.

While Buckingham Palace officials swept Mrs Thatcher in to see the queen, Denis was whisked off to a private drawing room where he was offered a cup of tea. Not to his taste, he declined it, opting for a gin and tonic instead.

In the queen’s private audience room, no one else except the monarch and prime minister were present. Thatcher would have kneeled before her sovereign and been invited to form the next government. The British constitution is unwritten and, unlike the United States, there is no single document outlining its fundamental principles. Rules have arisen out of legislation, precedent and custom.

The kissing of hands is a sober ritual that takes place in the queen’s audience room. It is full of meaning and symbolism. The prime minister takes the official oath, receives the seal of office and kisses hands in a symbol of fealty and loyalty, before being asked to form a government in the sovereign’s name. Following a general election, the monarch always calls upon the leader of the majority party in the House of Commons to form the government. Not until that moment is the election of the people’s choice for prime minister ratified by the sovereign. In many ways, this is just a formality; in reality, the democratic process is already in motion, and no modern monarchy would ever question the people’s choice.

Margaret would then, under full glare of the world’s press, take possession of the highest political office in the land, and with it the occupancy of 10 Downing Street, and Chequers, a country house in Buckinghamshire also allocated to the British premier. Already, her personal assistant, Cynthia Crawford, known to everyone as ‘Crawfie’, was on her way to Number 10, with her staff and boxes of files, typewriters and other office equipment. The handover of power started the moment the election results were counted.

When the necessary formalities were completed by the queen and Mrs Thatcher, the new premier and her consort, Denis, were driven to Downing Street accompanied by a police motorcycle escort. The palace guards saluted Thatcher on the way out as she was now prime minister, something they hadn’t done on the way in.6

The people’s choice finally had the job she had craved. Downing Street was crammed with reporters, photographers, cameras and microphones. Crowds of enthusiastic supports sang ‘For She’s a Jolly Good Fellow’ as the official car made its way through, and Mrs Thatcher was deposited just outside the most famous door in the land. Flanked by uniformed police officers she recited the prayer of St Francis of Assisi:

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony.

Where there is error, may we bring trust.

Where there is doubt, may we bring faith.

Where there is despair, may we bring hope.

After adopting the royal ‘we’ on her first day in the job, albeit in disguise, Mrs Thatcher then turned and walked through the door of what was to be her new home for the next eleven and a half years.7

Her success was a global news story, a new female head of government. It had happened before, Indira Gandhi in India, Golda Meir in Israel and Sirimavo Bandaranaike in Sri Lanka. That Britain, a nation bound by tradition and custom, could elect a woman was inconceivable. Margaret Mead, the noted anthropologist, once said that a clever woman must have two attributes to fulfill her intent: more energy than normal mortals and the ability to outwit her culture.8 Margaret Thatcher could not only survive on four hours sleep, but she also had the wherewithal to break down the barriers of an inferior social background and gender handicap.9

On that first night in Downing Street, she shared a Chinese takeaway with her team in the grand setting of the State Dining Room, and worked until late.10 She started as she meant to go on.

It would, however, be wrong to think of the queen or any British monarch as merely a crowned and anointed ornamental icon. Margaret said herself, ‘Anyone who imagines that they are a mere formality, or confined to social niceties, is quite wrong; they are quietly businesslike, and Her Majesty brings to bear a formidable grasp of current issues and breadth of experience.’11

Prime ministers come and go with elections, but the monarch endures as head of state. Although Elizabeth II lacks direct power, she is a block on any prime minister having total control. For as long as she reigns, no premier can be number one, they will always remain in second place.

The reality is that the queen has far more power than she dares to use. She has been successful with most prime ministers because she has never rocked the boat or posed a threat as an alternative power broker. The monarch’s role in the British constitution is limited to ‘… the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn’.

Throughout Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, Elizabeth exercised these very particular rights every Tuesday at 6.30 p.m. No one knows what was said during the weekly visits Mrs Thatcher made to the audience room at Buckingham Palace, but they took place for over a decade. No one else was present; no notes were taken on either side and both parties have an unspoken agreement never to repeat what was discussed, even to their spouses.12 The queen had received her seven previous prime ministers in the same room, starting with Sir Winston Churchill when she was only 25 years old; Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan, Alec Douglas-Home, Harold Wilson, Edward Heath and James Callaghan all followed. The room they meet in is large, and painted duck egg blue with high ceilings. On the walls are two paintings by Canaletto and two by Gainsborough. At the centre of the r...