![]()

1

A CITY AND ITS PHASES

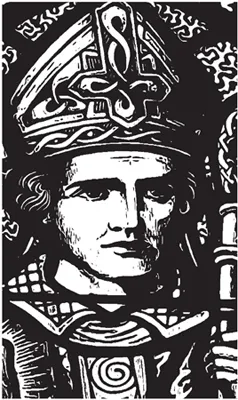

ST FINBARRE, PATRON SAINT OF CORK

A legend records that the origins of Cork City begins at the source of the Lee in the scenic Shehy Mountains at the heart of which lies the cherished pilgrimage site of Gougane Barra (Finbarre’s rocky cleft). Cork City’s patron saint, St Finbarre, reputedly established one of his earlier monasteries on an island in the middle of Gougane Lake. Legend has it that he then left to walk the river valley at the mouth of which he established the monastery at what is now the site of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral in Cork City. His myth endures in the valley and it is the legacy of St Finbarre that gives the city and valley its core spiritual identity and an origins story. Across the valley, there are churches named after Finbarre and a number of memorials depicting the saint in churches in the form of stained-glass windows and statues.

There are several ways of spelling the saint’s name, but Finbarre is the most common. His connection seems rooted in several religious sites across the Lee Valley from source (Gougane Barra) to mouth (Cork City). Finbarre’s Life was initially composed in Latin and was then passed down along three principal lines, each resulting in a major revision of the original text. In all, Finbarre’s Life survives in thirty-five manuscripts and twenty-one copies in early vernacular. Finbarre’s written vernacular life has undergone little major change between its earliest and latest extant copies. These date respectively from about 1450 to 1874. Finbarre’s original Life seems to have been composed, perhaps as part of a collection, in Cork between AD 1196 and 1201, some twenty-five years after the arrival of the Normans in south Munster. This was a time of reform in the Catholic Church.

St Finbarre, depicted in stained-glass window in church of the Immaculate Conception, Farran, County Cork.

Finbarre’s hermitage was located around the area of present-day Gillabbey Street. It grew to be an important religious centre in southern Munster, providing ecclesiastical services in the form of a church and graveyard, and secular services in the form of a school, hospital and hostel. The annals record that languages such as Latin were taught at the school and that it was one of the five primary sites in Ireland in terms of size and influence. Word quickly spread of the monastery’s valuable contribution to society, and it became necessary to expand the site. Between AD 600 and 800, a larger hermitage was constructed east of the original site, on open ground now marked by St Fin Barre’s Cathedral. It is believed that over the subsequent centuries this hermitage grew to a point where it extended along the northern district of the lough, and extended on both sides of Gillabbey Street and College Road about as far as the locality now occupied by University College Cork (UCC).

Around the year AD 623 St. Finbarre died at the monastery of his friend, St Colman, at Cloyne in east Cork. His body was returned to his hermitage and his remains were encased in a silver shrine. Here they remained until 1089 when they were stolen by Dermod O’Brien. The shrine and the remains have never been recovered. Legend has it that the location of his tomb is just to the south-east of the present cathedral, overlooked by the famous Golden Angel. St Finbarre’s feast day is celebrated on 25 September. As the city’s patron saint he is still greatly revered.

VICIOUS VIKINGS

All that is known of the first recorded attack on the monastery at Corcach Mór na Mumhan was that it occurred in AD 820 and that the most valuable treasures were plundered. It is also known that it was raided four to five times in the ensuing 100 years. The marshy environment would not have been entirely welcoming, but the Vikings nonetheless established a settlement or longphort here. We cannot be sure of the exact location of the Viking town, but it is known that in AD 848 a settlement called Dún Corcaighe (Fort of the Marshes) was besieged by Olchobar, King of Caiseal from north Munster. It is thought that it was located on an island, the core of which could be marked by South Main Street, an area that was developed in ensuing centuries by other colonialists. With this in mind, Dún Corcaighe would have been located strategically near the mature stage of the River Lee, and therefore would have controlled the lowest crossing-point of the river, whilst being sheltered by the valley sides. The Norse invaders established a maritime network with other Viking ports, namely those at Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, and Limerick.

The Viking presence in Corcach Mór na Mumhan was interrupted by invaders from Denmark around AD 914 who also attacked other Viking towns in Ireland and gained control of them. In Cork, these new invaders – the Danish Vikings – started off by raiding the monastery on the hillside but soon turned their attention to wealthier and more powerful Gaelic kingdoms in Munster. The Danes decided to settle in Ireland. They took over and adapted existing Norwegian bases and constructed additional ones to a similar but larger design. Unfortunately, the historical and archaeological information available regarding a Danish settlement at Cork is poor compared to that arising from excavations in Waterford and Dublin. Nevertheless, there are some clues that give an insight into the location, structure and society of Danish Viking-Age Cork. It is known that there were at least three main areas of settlement: firstly, they lived on the southern valley side next to the monastery, the core area of which is present-day Barrack Street; secondly, they settled on a marshy island now the location of South Main Street, the Beamish and Crawford Brewery, Hanover Street and Bishop Lucey Park; and thirdly they settled on the adjacent northern valleyside, now the area of John Street in Lower Blackpool.

The publication Archaeological Excavations at South Main Street 2003-2005 (2014) records Hiberno Norse structures found under South Main Street area. Two to three metres underneath our present-day city, archaeologists exposed the remains of timber structures. The dendrochronological dates of the timbers found on the site suggest that there was continuous felling of trees and construction of buildings and reclamation structures from just a few years before 1100 to 1160. So here on a swamp 900 years ago, a group of settlers decided to make a real go at planning, building, reconstructing and maintaining a mini town of timber on a sinking reed-ridden, riverine tidal space.

A SAFE HARBOUR FOR SHIPS

By the early 1170s the Anglo-Normans had taken control of large tracts of land from Waterford to Dublin. In 1172 they turned their attention to Cork. Two Anglo-Norman lords, Milo de Cogan and Robert Fitzstephen, were despatched to Corcach Mór na Mumhan with a small land force to confront and dispossess the Vikings and chief of the McCarthys, Dermod McCarthy, of his lands in counties Cork and Kerry. Once they had been defeated, Fitstephen and De Cogan began the transformation of the settlement into an Anglo-Norman town. It was to become one of fifty-six early Anglo-Norman walled towns established in Ireland, some re-founded on adapted and extended Viking settlements sites. Initially, they noted that the Danish settlement on the marshy island was ‘fortified’ and had a gate (‘porta’) leading into it. The nature of the fortification, whether it was stone or timber, was not recorded. Incorporating elements of the old settlement, the newcomers instigated many fundamental changes to the town.

The name of the town was shortened to Corke. The renaming was significant as it was the first instance of the anglicising of a Gaelic name. In the late 1100s, Henry II chose Bristol as the model to be followed in developing manorial towns in Ireland, especially in issues such as liberties, privileges and immunities. Corke was to have its own mayor, sheriffs, and a corporation of councillors. The city still possesses these legacies. The term is now Lord Mayor and the Corporation a City Council.

Between the 1170s and 1300s, a stone wall, on average 8 metres high, became the new perimeter fence for the old Viking settlement area on the island, which was accessible via a new drawbridge built on the site of the Viking bridge, Droichet. Beyond this wall, a suburb called Dungarvan (now the area of North Main Street) was established on a nearby island.

By 1317 the full circuit, which included the extension of the wall around Dungarvan, was complete. Thus the redevelopment of the town walls created one single walled settlement (6½ha. in extent) instead of a walled island with an unfortified island settlement and Dungarvan outside it. Within the town a channel of water was left between the old walled settlement and the newly encompassed area of Dungarvan, with access between the two provided by an arched stone bridge called Middle Bridge. A millrace dominated the western half of this channel, while the remaining eastern half was the town’s central dock.

The wall had mural towers at regular intervals that projected out and were used as lookout towers by the town’s garrison of soldiers. The walled town extended from South Gate Bridge to North Gate Bridge and was bisected by long spinal main streets, North and South Main Streets. These were the primary routeways and although narrower than the current streets, would have followed an identical plan. They would also have been the main market areas.

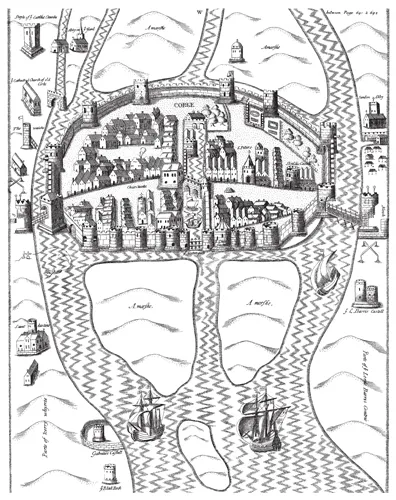

The walled town of Cork, as depicted in Sir George Carew’s Pacata Hibernia, or History of the Wars in Ireland, vol. 2 (1633) .

The town was now well defended and all those seeking to gain entry had to use one of the three designated entrances: one of the two well-fortified drawbridges with associated towers or the eastern portcullis gate. The first drawbridge, allowing access from the southern valleyside, was South Gate Drawbridge, while entry from the northern valleyside was via North Gate Drawbridge. From 1300 to 1690 these were the only two bridges spanning the River Lee. There are still bridges on these sites today and they still possess the names North and South Gate Bridge. The current South Gate Bridge dates to 1713 while the North Gate Bridge dates to 1961.

The third entrance overlooked the eastern marshes and was located at the present-day intersection of Castle Street and Grand Parade. Known as Watergate, it comprised a large portcullis gate that opened to allow ships into a small, unnamed quay located within the town. On either side of this gate, two large mural towers, known as King’s Castle and Queen’s Castle, controlled its mechanics.

The Anglo-Normans consolidated this port by establishing new export destinations and by the end of the seventeenth century, the walled town of Cork was exporting to other European ports such as to Bordeaux, in France, and to a large range of English Ports such as Bristol, Chichester, Minehead, Southampton and Portsmouth. Trading contacts were also made across the Atlantic Ocean to eastern North American ports such as Carolina and those in the Caribbean, trading goods such as beef and butter. In addition, the sheltered nature of the mature river valley and Cork harbour has provided a safe berth for ships right through the ages.

The coat of arms of the city comprises two battlemented towers with a ship, depicted as a medieval galleon, in between. The arms are said to depict King’s and Queen’s Castles, which operated Watergate. A Latin motto is attached: Statio Bene Fida Carinis (a safe harbour for ships).

A VENICE OF THE NORTH

For nearly 500 years (c.1200-c.1690), the walled port town of Cork remained as one of the most fortified and vibrant walled settlements in the expanding British colonial empire. However, economic growth as well as political events in late seventeenth-century Ireland, culminating in the Williamite Siege of Cork in 1690, provided the catalyst for large-scale change within the urban area. The walls were allowed to decay and this was to inadvertently alter much of the city’s physical, social and economic character in the ensuing century.

By John Rocque’s Map of Cork in 1759, the walls of Cork were just a memory – the medieval plan was now a small part in something larger – larger in terms of population (from 20,000 to 73,000) and in terms of a new townscape. A new urban text emerged with new bridges, streets, quays, residences and warehouses built to intertwine with the natural riverine landscape.

The 1759 map is impressive in its detail. John Rocque (c.1705-62) was a cartographer and engraver of European repute. He could count among his achievements maps of London, Paris, Berlin and Rome. The features that stand out on his Cork map are the canals and the links to changing technologies, reclamation, bridge construction, river bank consolidation, creation of quays – all linked to new emerging urban civilisation within a network of canals, reminiscent of Venice, Amsterdam, Copenhagen – Cork’s central canal lined the centre of the newly reclaimed area, admirable buildings on both sides bearing a special relationship with the water. By 1790, many of these were to be filled, creating wide and spacious streets like St Patrick’s Street, Grand Parade and the South Mall.

During the eighteenth century Cork gained the nickname the Venice of the North. It would be great to point to a myriad of real physical Venetian imagery and perspectives in eighteenth-century Cork but this terminology seems only to exist in the legacies of that time. Indeed it is more commented upon in nineteenth-century antiquarian books and late twentieth-century history books of Cork than in the traveloques of eighteenth-century antiquarians.

Economically, in the eighteenth century, the city was booming. By 1730, the population had increased to 56,000 and by 1790 it was 73,000. This was a large increase since a population of 20,000, 100 years previously in 1690. The settlement’s harbour and hinterland maintained a lucrative provision trade. Cork’s exports comprised on average 40 per cent of the total export from Ireland with just over 70 per cent of this total sent to the European mainland. The list of countries included; Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, Great Britain and the coastal islands, Holland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Barbadoes, Turkey and Greenland. Cork held 80 per cent of the Irish export to England’s American colonies. The main ports include Carolina, Hudson, Jamaica, Montreal, Quebec, New England, New Foundland, New York, Nova Scotia, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland and the West Indies. Exports were also sent to New Zealand and the Canaries. By 1800, Cork was reputed to be the most noteworthy transatlantic port.

HUGUENOTS AND QUAKERS

The north-eastern marshes became a significant area of development for the Huguenot congregation in Cork. By the mid-1700s, over 300 Huguenots had established themselves in Cork City. Many of them worked as trades people, especially in the textile industry and in the manufacture of linen and silk. The Huguenots were also involved in property development and one of the first Huguenot families to develop property was Joseph Lavitt whose family were primarily involved in overseas trade and sugar refining and constructed Lavitt’s Quay in 1704. The areas of present-day French Church Street, Carey’s Lane and Academy Street in the city centre are located at the core of the Huguenot quarter with the name ‘French Church’ also reflecting their involvement in townscape change in Cork in the early eighteenth century.

To the west of the crumbling walled town, the religious group, the Quakers reclaimed and developed large portions of the marshy islands. This community had been in Cork since 1655, but it was only in the early 1700s that they were legally given the opportunity to develop their own lands.

The Quaker movement began in northern England around 1650 and developed out of religious and political conflict. Also known as the Religious Society of Friends, they were a breakaway group from mainstream Protestantism. With the presence of massive opportunities for trade, the Quakers established themselves in Cork City and in other Munster towns such as Bandon, Skibbereen, Charleville and Youghal.

One of the first Quaker pioneers in the development of the western marshes was Joseph Pike, who purchased marshy land in 1696, now the area of Grattan Street. Another key player was John Haman, a respected linen merchant who also owned land in the northern suburbs. Minor players included the Devonshire family, the Sleigh family and the Fenn family (Fenn’s Quay today marks their land). In the eastern marshes, a Quaker by the name of Captain Dunscombe bought land, now the area of the multi-storey car park on the Grand Parade and part of present-day Oliver Plunkett Street.

One noted Quaker, William Penn, spent much time in the Cork area. Born in 1644 in Tower Hill, London, William was the son of Admiral William Penn. Educated at Oxford, he was expelled for non-conformity, reputedly because of his contact with the Quaker movement. Subsequently, he went to France to study for two years at the Protestant University of Saumur, before returning to London to study law at Lincoln’s Inn. In the 1650s, Oliver Cromwell gave his father a considerable estate, the castle and manor of Macroom in County Cork. On the accession of Charles II in the 1660s, he was dispossessed of this property and was compensated with lands in Shanagarry, County Cork. In 1667, his father sent him to manage the estate. While in east Cork, he was influenced by his friend, a Quaker, Thomas Lee and converted to Quakerism. William visited the walled town of Cork in 1667 and attended a Quaker meetin...