- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

On 2 September 1845, the convict ship Tasmania left Kingstown Harbour for Van Diemen's Land with 138 female convicts and their 35 children. On 3 December, the ship arrived into Hobart Town. While this book looks at the lives of all the women aboard, it focuses on two women in particular: Eliza Davis, who was transported from Wicklow Gaol for life for infanticide, having had her sentence commuted from death, and Margaret Butler, sentenced to seven years' transportation for stealing potatoes in Carlow. Using original records, this study reveals the reality of transportation, together with the legacy left by these women in Tasmania and beyond, and shows that perhaps, for some, this Draconian punishment was, in fact, a life-saving measure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Van Diemen's Women by Joan Kavanagh,Dianne Snowden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Irish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Poverty Alone Drove Her to

Do What She Has Done1

Centuries of colonialism had a huge impact on the native Irish, disenfranchising them and introducing a new culture and tradition. Tensions arising from religious, political, economic and land rights were endemic.

Poverty increased despite the continuation of the economic expansion of the latter half of the eighteenth century and the prosperity of agriculture, particularly during the Napoleonic Wars.2 In 1815, the war ended and economic conditions worsened. The problem was exacerbated by rapid population growth. The Irish population increased significantly in the first half of the nineteenth century. An estimated 2.3 million people lived in Ireland in 1754. By 1841 this had increased to 8.1 million.3 By 1845, it had reached about 8.5 million.4 One in eight of those alive at the onset of the Great Famine, An Gorta Mór, perished.5

The population increase was particularly significant as the country relied upon agriculture; the labouring classes and small holders, especially in the west, could barely survive unless they supplemented the produce of their holdings with wages.6 There was greater competition for land and increased unemployment. Agriculture was the main source of employment, although there was some industry in Ulster. Small farmers, usually renting over 15 acres, lived side by side with cottiers – those who rented about 5 acres of land but who also needed to work to supplement their income. At the bottom of this triangle were the labourers who rented ‘conacre’, usually plots of less than one acre on which to grow a single crop of potatoes. For those who could not find work as labourers in Ireland there was seasonal work in Scotland or work as navvies building the railways and canals in England. Others turned to begging.7

Begging for Alms. (NLI, 2033 (TX) 58(C), image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Areas not usually ploughed were cultivated and land was divided into increasingly smaller plots.8 According to Cecil Woodham-Smith, ‘Unless an Irish labourer could get hold of a patch of land and grow potatoes on which to feed himself and his children, his family starved … the possession of a piece of land was literally a matter of life and death.’9 For the agricultural labourers and cottier class in Ireland in the 1840s, the potato was a staple food; at least one third of the population was dependent upon it.10

Conditions were worse in the west and the south where population growth had been fastest and where holdings were the smallest; families living on the smallest holdings were entirely dependent on the potato.11 By about 1840, the condition of the poor grew more desperate.12

The agricultural class of Limerick in 1837 was described in Samuel Lewis’ topographical dictionary:

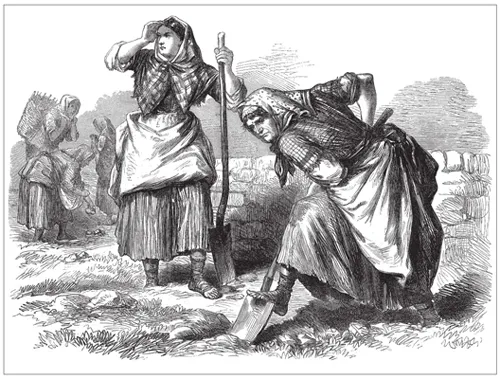

Women at field-work in Roscommon. (Reproduced with permission of Roscommon County Council: Library and Archive Services)

Cottages with a view of the obelisk at Killiney Hill, County Dublin, by Samuel Frederick Brocas. (NLI, 2064 (TX) 94, image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

The peasantry differ little in their manners, habits and dwellings from the same class in the other southern agricultural counties; their dwellings being thatched cabins, their food potatoes with milk and butter occasionally, their fuel turf, their clothing home-made frieze and cheap cotton and stuffs: their attachment to their neighbourhood of their nativity, and their love of large assemblages, whether for purposes of festivity or mourning, are further indications of the community of feelings and customs with their country men in their surrounding counties.13

About the same time, Alexis de Tocqueville, the French historian and philosopher, visited Ireland; he described the living conditions of the agricultural class in a village in Connaught:

All the houses in line to my right and my left were made of sun-dried mud and built with walls the height of a man. The roofs of these dwellings were made of thatch so old that the grass which covered it could be confused with the meadows on the neighbouring hills.

In more than one place I saw the flimsy timbers supporting these fragile roofs had yielded to the effects of time, giving the whole thing the effect of a mole-hill on which a passer-by has trod. The houses mostly had neither windows nor chimneys: the daylight came in and smoke came out by the door. If one could see into the houses, it was rare to notice more than bare walls, a rickety stool and a small peat fire burning slowly and dimly before four flat stones.14

REGIONAL DIVERSITY

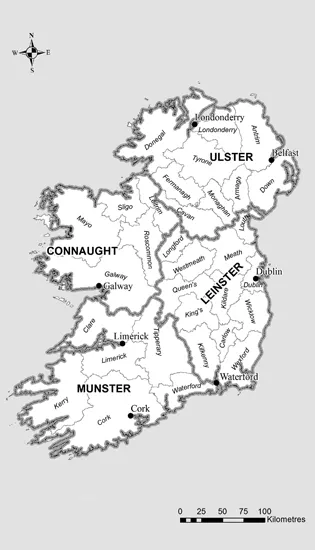

For administrative purposes, Ireland is divided into provinces, baronies, counties, parishes and townlands. The women of the Tasmania (2) came from thirty-one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Sligo was the only county not represented. Although geographically Ireland is a small island, historically it is characterised by regional diversity. The life experiences of the women living in the province of Ulster and those living in Munster, for example, were significantly different.

The circumstances of the Irish, and especially the poorer classes, can best be understood against a background of colonisation and suppression by the English Crown dating back at least to the sixteenth century. The surnames of the women on board the Tasmania (2) reflect the outside influences that dominated Irish history from the earliest times; the Norman invasion in 1169 and the plantations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.15 The surname Davis is of Welsh origin and the name Butler can be traced back to the Normans. While over eighty of the surnames of the women on board are of native Irish origin, the remainder stem from the Normans and English, Scottish and Welsh settlers, not forgetting those who came seeking trading opportunities and stayed. However, surnames that may appear to be non-Irish may in fact be anglicised versions of Irish names.16

Provinces, counties and main towns of Ireland. (Courtesy of Martin Critchley)

Property was increasingly in the hands of English landowners, many of whom were absentee landlords who showed little compassion for those who worked the land. Land agents left in charge – sometimes a relative of the absentee landlord or a local person – could be particularly callous.

The suppression of the Irish was manifested in a number of political ways. As a result of the war between Protestant William III and Catholic James II, the Penal Laws, commencing in 1691, were enacted. These laws not only restricted the practice of Catholicism but prevented Irish Catholics purchasing or inheriting property, holding political, civil or military office, standing for political or public office, or voting in parliamentary elections. A Catholic landholder could also be dispossessed of his land by a Protestant relative. The laws were in place until 1829, when the Roman Catholic Relief Act was introduced.17 In the eighteenth century, settlers of British extraction owned approximately 80 per cent of the land. This new Protestant ruling class, the Protestant Ascendancy, had exceptional influence on the way the country was governed. It ruled Ireland for the next two centuries. While the ruling elite inhabited grandiose buildings and townhouses in Dublin and on country estates, the majority of the population – constrained by religion and unable to own land – had restricted access to political and economic activities.18

Throughout the country the ‘big houses’ of the landlords were appearing on the Irish landscape, mirroring their counterparts in Britain: Castletown House in County Kildare; Westport House in County Mayo; Mount Wolseley, Tullow, County Carlow; Strokestown Park House in County Roscommon; Castle Ward in County Down; and Powerscourt House in County Wicklow are just a few of the imposing houses constructed in the eighteenth century. Landlords, some of whom were absentee, let their land to ‘middlemen’ tenants on very long leases with fixed rents. These ‘middlemen’, some descendants of the dispossessed Irish, in turn sublet to undertenants in order to generate an income. In the early years of the nineteenth ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Authors’ Note

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Foreword by Mary McAleese

- Abbreviations

- Conversions

- Glossary

- Introduction More Sinned Against Than Sinning?

- 1 Poverty Alone Drove Her to Do What She Has Done

- 2 The Law Must Take Its Course

- 3 ‘These Unfortunate Females’: The Women of the Tasmania (2)

- 4 Banished Beyond the Seas

- 5 The Floating Dungeon

- 6 A New Life in a Strange Land

- 7 Behind Stone Walls

- 8 A Sad Spectacle of Humanity

- 9 All are Certain of Marrying, If They Please

- 10 A Mere Accident of Birth

- 11 New Families in a New Land

- 12 Journey’s End

- Conclusion The Legacy of Eliza Davis and Margaret Butler

- Appendix I Trial Statistics

- Appendix II The Women of the Tasmania (2)

- Appendix III The Children of the Tasmania (2)

- Appendix IV The Sick List of the Tasmania (2)

- Select Bibliography

- Copyright