![]()

1

THE NEW POOR LAW

In November 1836, a ‘most daring’ attempt was made to murder Richard Ellis, the master of Abingdon Union Workhouse. Shots were fired from the workhouse garden through the sitting-room window, narrowly missing the master’s sister and an elderly pauper. Abingdon was the first of a new breed of workhouse built as a result of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834. The workhouse had been open for inmates for about a month and it was believed that the violent attack against the master was a protest against the new Poor Law legislation.1

Before 1834, each parish was responsible for its own poor. The able-bodied who had fallen on hard times or were unemployed, for whatever reason, could expect to be granted outdoor relief from the parish overseer of the poor in his or her own home. The sick and elderly might also be looked after in a small parish workhouse which was ‘seen as a relatively unthreatening and even friendly institution’.2

THE NEW POOR LAW IN ACTION

After 1834, there were four main changes to the Poor Law system. Firstly, a central authority, called the Poor Law Commission, was to regulate the new Poor Law. The Poor Law Commission, based in London, was made up of three commissioners who had the power to issue rules and regulations for the new Poor Law. They were supported in their role by assistant commissioners. (From 1847, responsibility for the Poor Law passed to the Poor Law Board. After 1871, the Poor Law was administered by the Local Government Board.)

Secondly, parishes were to group together into ‘unions’ to benefit from economies of scale. It was proposed that approximately thirty parishes join together to create each new union. Each union was to be run by a board of guardians which would meet weekly and report regularly to the Commission. It was the responsibility of the assistant commissioners to oversee the setting up of the new unions. However, it was no easy matter to obtain agreement from each parish, and those parishes which had joined together under earlier legislation known as the Gilbert Act often refused to be brought into the new system.

Thirdly, accommodation was to be provided for paupers in workhouses under ‘less eligible’ or worse conditions than those of the poorest independent labourer. The intention was that only the truly destitute would seek relief in the workhouse and that it would be a last resort. Any applicant who refused to enter the workhouse was said to have ‘failed the workhouse test’.3

In the 1830s and 1840s, these new workhouses, the ‘unions’, like the one at Abingdon, sprang up across England and Wales approximately twenty miles apart. The buildings were austere and prison-like and were deliberately designed to be starkly different from the more domestic parish workhouses of the eighteenth century. The design and appearance of the new union workhouses created a real visual deterrent and was ‘meant to represent the new approach to relief provision.’4

The old parish workhouse at Framlingham, Suffolk.

Finally, and most contentiously, ‘outdoor’ relief for the able-bodied was to be minimal so that those applying for poor relief had to enter the workhouse. The Commission’s Report of 1834 concluded that ‘the great source of abuse is outdoor relief afforded to the able-bodied’.5 One of the main objections to building new workhouses for both paupers and guardians was the stipulation that outdoor relief be reduced or abolished to the able-bodied poor. To withdraw such a basic, traditional right, and force paupers to enter the workhouse was thought to be inhumane and implied that poverty was a crime.

In addition, outdoor relief was considerably cheaper than indoor relief. It was argued that the building of new workhouses would be a heavy burden on the ratepayers. The small Lampeter Union delayed building a new workhouse until 1876 because the guardians calculated that ‘if a man went into the workhouse he would cost the Union 1s 9d a week, but if he was given relief outside the workhouse it would cost only 9d, a saving of 1 shilling per week.’6

Many unions chose to adapt existing parish workhouses rather than bear the expense of building new ones. This decision was not popular with the Poor Law Commission, as adapted parish workhouses were rarely able to provide sufficient accommodation to classify the inmates separately.

By 1840, 14,000 parishes had been incorporated into unions with only 800 parishes remaining outside the system. However, most of the 350 new workhouses built by 1839 were in the south of the country.7

PROTESTS AGAINST THE NEW WORKHOUSES

A major flaw in the legislation of 1834 was that the Commission had no power to order the building of new workhouses, although they could order alterations to existing buildings. In practice, unions could repeatedly delay implementing the new Poor Law, and many chose to do so.

The authors of the Report failed to recognise the differences between the industrial north and the more agricultural south and thus their contrasting experiences of poverty and treatment of the poor. The attack at the Abingdon Union Workhouse was by no means the only form of protest against the Poor Law Amendment Act, dubbed by critics the ‘Whig Starvation and Infanticide Act’. With resistance strongest in the north, there were riots against the new Poor Law in 1837 and 1838 in Oldham, Rochdale, Todmorden, Huddersfield and Bradford.8

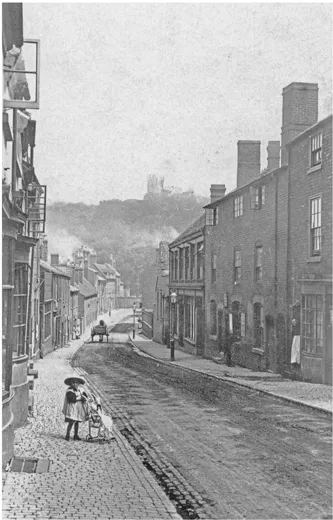

The slums of Tower Street, Dudley, where the old parish workhouse was situated.

As a result, there were very few workhouses built in the West Riding of Yorkshire or in Lancashire until the 1850s and 1860s.9 However, protests against the new Poor Law were not confined to the north. There was staunch opposition in Wales while few new workhouses were built in Cornwall, and in Dudley, Worcestershire, the new union workhouse was not opened until 1859.10

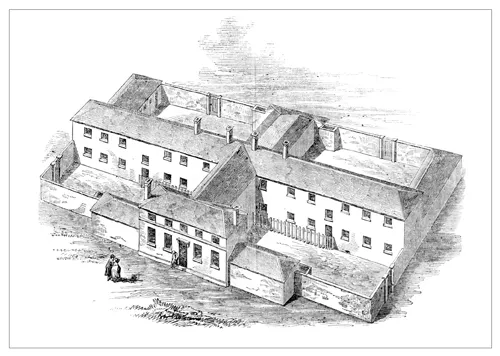

The Andover Union Workhouse built to a standard cruciform design. (Illustrated London News, 7 November 1846.)

DESIGNS OF NEW WORKHOUSES

The Poor Law Commission issued model plans for the building of the new union workhouses, some of which were produced by the architect Sampson Kempthorne. Although the unions could, in theory, invite designs from other architects and builders, in practice, most of the new workhouses were based on one of Kempthorne’s designs. There were two main designs for a three-storey mixed workhouse – one cruciform and the other Y-shaped with a hexagonal boundary wall.11

The first new union workhouse at Abingdon was a variation on Kempthorne’s first Y-shaped design with an extra fourth storey. The British Almanac noted how it provided ‘with great facility, the division into six yards, for the better classification of the inmates. In the centre [of the] building are the governor’s rooms, for the inspection of the whole establishment.’12

Whichever design was chosen, the layout of every union workhouse was similar. In each design, there were six exercise yards for the infirm, the able-bodied, and children aged seven to fifteen, with the sexes segregated. These areas were separated by high walls. There were day rooms for the infirm and able-bodied, a schoolroom and a master’s parlour which was usually placed at a central position so that he could observe the day-to-day routine in all parts of the workhouse.

The walls which formed the boundaries around the exercise yards to the outside world contained the workrooms, washrooms, bakehouses, the ‘dead house’, the refractory ward and the receiving ward. On the first floor were the dormitories, the master’s bedrooms, the dining hall and the Board Room where the guardians would hold their weekly meetings. The lying-in ward for expectant mothers and the nursery was on the third floor separating the boys’ and girls’ bedrooms.13

The design of the new union workhouses allowed for the most contentious of systems to be put into place: the classification and segregation of the sexes and families.

NOTES

1. Higginbotham, P., Abingdon Workhouse <http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Abingdon/> Oxford University web, Oxford, 2000

2. Murray, P., Poverty and Welfare 1830-1914, (1999), p26

3. Ibid., p26

4. Englander, D., Poverty and Poor Law Refo...