- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

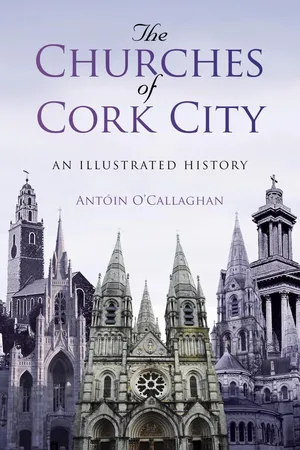

About this book

The churches, chapels and meeting houses of Cork are the bedrock of the city. They represent the finest of architecture, house some of our most treasured art and their development mirrors and records the growth of the city itself. A comprehensive and accessible guide for locals, tourists and historians, this work provides a fascinating insight into the wider history of Cork for well over a thousand years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Churches of Cork City by Antoin O'Callaghan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Five

THE EIGHTEENTH AND

NINETEENTH CENTURIES

Thus far, the historical narrative of churches in Cork city has been based to a large extent on two main sources. Firstly, the works of scholars who have deciphered and interpreted a range of documents, both complete and incomplete, that have been preserved in a variety of ways through the centuries. These include extracts from the annals and lives of those who lived in Celtic and Viking times; historical accounts preserved in the archives of the orders that have served in the city since Norman times; and a range of other tracts, such as charters, property leases, wills and private letters. Secondly, tradition and folk memory that has been passed on through the ages has contributed to the historical narrative. From the eighteenth century onwards, as is the case with other physical structures such as bridges, the narrative is greatly enhanced by the actual presence on the landscape of a number of churches built in that period. Thus, in the cases of St Anne’s Shandon, St Finbarr’s South Chapel and the Catholic Cathedral of St Mary and St Anne, people can enter the buildings today, as generations before them have done. The historical narrative from this point can therefore entail a physical dimension whereby people can literally touch history.

ST ANNE’S SHANDON

The church of St Anne Shandon is one of the most famous landmarks in Cork. Named after the mother of the Blessed Virgin Mary, it was built in 1722 on the site of the Chapel of St Mary that was destroyed during the 1690 siege of Cork. St Anne’s was famously immortalised by Fr Prout in his The Bells of Shandon, which highlighted:

Thy bells of Shandon that sound so grand on

The pleasant waters of the River Lee.

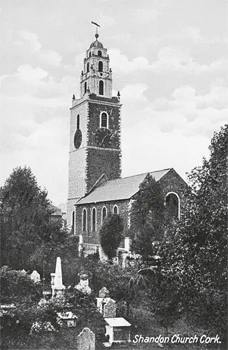

Physically the church is an imposing structure, with its tower rising 120 feet, two sides faced in limestone and two in red sandstone, and its steeple, which is topped with a gilded dome and a golden-coloured fish. From the middle of the nineteenth century, this was where all Corkonians looked for a time check, whether they were to the north, south, east or west of the tower.

As previously mentioned, following the destruction of the church of St Mary in 1690, a replacement St Mary’s was built in 1693 on a site near that of the original church, closer to the river at the junction of Mallow Lane – now Shandon Street – with Blarney Lane. Writing in 1952, the Revd J.W.T. Tuckey says that St Anne’s Shandon ‘was erected by subscription in 1722 as a chapel-of-ease to St Mary’s Shandon’.123 Regarding St Anne’s, while McNamara suggests that the same Coltsman who designed the North and South Gate Bridges, as well as Christchurch, was probably the ‘author of the work’,124 the Revd Tuckey tells us that it has been said that the sandstone sides came from the ruins of Shandon Castle, which once stood nearby, and that the limestone faces were made with the ruins from the Franciscan abbey that once stood at the North Mall.

St Anne’s Shandon from an old postcard. (Courtesy Michael Lenihan)

The steeple is constructed of hewn stone from the Franciscan abbey where James II heard Mass and from the ruins of Lord Barry’s castle, which had been the official residence of the Lords President of Munster and from which this quarter of the city takes its name – Shandon (sean dún), signifying in Irish an old fort or castle.125

The upper steeple section was added in the 1740s. In 1752, thirty years after construction began, the famous bells were added.126 These were cast by Abel Rudhall of Gloucester in 1750 and, following their installation in 1752, were heard in the city for the first time on 7 December of that year, on the occasion of the marriage of Henry Harding to Catherine Dorman. Each of the eight bells has an inscription, as follows:

When us you ring we’ll sweetly sing

God preserve the Church and King

Health and prosperity to all our benefactors

Peace and good neighbourhood

Prosperity to the city and the trade thereof

We are all cast at Glouster in England by Abel Rudhall 1750

Since generosity has opened our mouths,

our tongues shall ring aloud its praise

our tongues shall ring aloud its praise

I to the Church the living call, and to the grave do summon all.

Prior to the installation of the bells, a single bell had served as the means of calling the faithful. This had been provided in 1745 by one Daniel Thresher, who also subscribed for the eighth of the complement put in the tower in 1752.

Because of the physical shape of the tower, it has been described as a ‘pepper-pot steeple’, on top of which stands a copper dome holding the weathervane in the shape of a salmon, which was added by the early 1770s. Regarding the symbolism of the fish, Rynne says that ‘the salmon fisheries of the Lee, from the Duke of Devonshire’s weir near the present city waterworks to the west of Blackrock, were internationally famous and the weather vane salmon is a clear reference to this’.127 However, the primary purpose of the structure is as an ecclesiastical building and so it can be suggested that the salmon ‘is a very appropriate sign to have on a church, as in the earliest days of Christianity, a fish was used as a symbol for the name of Our Lord’.128

Internally the church is quite simple in design. Smith describes it as ‘a very neat plain church’129 while Rynne describes it as having a simple basilican form – a nave and two aisles – but with a squared-off apse at its eastern end and no transepts. The communion rails are bow-fronted in shape, while the eastern stained-glass window portrays the Transfiguration of Our Lord. Other windows show the Raising of Lazarus and the Good Samaritan. Two relics of the old St Mary’s remain: a font with the inscription ‘Walter Elinton William Ring made this Pant at their charges’. A pewter bowl was inserted into this in 1773; it bears the names of the rector and churchwardens of that year. There is also a memorial to one George Piercy Esq., who died in 1635 in the vestry.

The famous Shandon clock is the work of James Mangan and was installed in 1847 on the instruction of the Corporation. An argument made in favour of the work was that the provision of such a public clock would be of great benefit to the poor of the city because, without a way of ascertaining the hour of the day, they would not know at what time they should take their medicines. When it was installed, Shandon clock was the largest tower clock on these islands until the building of Big Ben in London in the 1850s. The dials on each face are 14 feet in diameter and the clock is probably best known by the name ‘The Four-Faced Liar’. This is because the minute hands on the east and west faces always go ahead of those on the north and south to account for prevailing weather conditions. However, as Tuckey points out, ‘complete agreement is reached once more at the hour’.130 Further embellishment of the church occurred in the 1880s with the installation of stained-glass windows made by Mayer and Company of Munich and the provision of an organ, which was made by Magahy and Son of Cork. Foreman with that company was Danny O’Callaghan of Blarney Street.

Shandon is now one of the oldest standing churches in the city. Therefore it is fitting, before moving to the next church built in the eighteenth century, to consider some other possible interpretations of aspects of the church’s history, given the turbulent times in which it was built.

Ian D’Alton, on the subject of Cork city’s Protestant culture, writes of ‘a wave of church-building and renovation in the early eighteenth century’, which included the rebuilding of Christchurch, St Nicholas’, St Paul’s and St Fin Barre’s between 1700 and 1740. The construction of St Anne’s in 1722 also falls within this period and although d’Alton suggests that there was an element of the ‘economic and social superiority of Protestant over Catholic’ in this, he also says that the building works ‘coincided with the reforming episcopacy of Peter Browne’.131 Thus matters religious were indeed relevant. Regarding St Anne’s, the site on which it was constructed was in a prominent location on the northern hills overlooking the city. As is the case with many churches, there is great symbolism associated with such a site choice. A new and imposing structure built on such a site would be seen from all parts of the city, thereby proclaiming the power of those undertaking such a venture. Not only would the power of the project’s sponsors be proclaimed; the power of the faith underlying the project would also be emphasised. Thus Shandon stood as a commanding declaration of the dominance of Protestantism in the city of Cork.

Another element of symbolism was that, located on a hilltop adjacent to the city as it was, the Shandon tower was closest to the heavens and to God. Thus, the faithful, journeying to the church for liturgies and services, journeyed closer to God. Two other aspects in the design of Shandon steeple were highly symbolic. The incorporation of the limestone that had previously been used in the Franciscan abbey on the North Mall was a statement that the new reformed order of Protestantism had overcome the flawed religion of Catholicism, destroyed it and incorporated it into a new and cleansed faith that now reached up to God, as symbolised by the new imposing church of St Anne. In Shandon was a Church transformed; the Protestant faith of the Church of Ireland. St Anne’s Shandon therefore stands as a symbol of the post-Reformation Protestantism of the eighteenth century. Thus, greater credence can be assigned to the suggestion that the fish on top of St Anne’s Shandon symbolises Christ, high in the heavens.

ST FINBARR’S SOUTH

The power and position of Protestantism in eighteenth-century Cork were manifested in the number, scale and architecture of the churches built for the faithful. Much of the funding for these projects was by subscription, with figures in the thousands quoted and donated by rich and poor alike. As well as highlighting that Christchurch cost over £5,000, Ian d’Alton also states that ‘in 1726 the parishioners of the two new churches of St Mary’s Shandon and St Paul’s raised £1,079, which was thirty per cent of the cost of building the churches’.132

What then of Catholicism? With the advent of the Hanoverian succession, the earliest green shoots of Catholic toleration began to emerge. By the mid-eighteenth century, Catholic merchants were actively participating in trade and commerce, generating wealth and establishing themselves as an acceptable part of a modernising Cork. This improvement in the situation of Catholics was marked by a significant church-building project in the 1760s. This was the building of the South Chapel or St Finbarr’s South, the first major Catholic project since the turbulence of recent centuries.

The Catholic Bishop of Cork at this time was Dr Richard Walsh. In 1760, he appointed a Dominican, Fr Daniel Albert O’Brien OP, as the spiritual leader of the Catholic community in the South Parish area. Fr O’Brien found that the Mass house or chapel that was in use was nothing more than a formerly thatched, barn-like building, located where the South Presentation Monastery and School subsequently stood. In 1727 it had been seriously damaged by fire, but was repaired the following year with a slated roof. It then had a capacity of up to 400 people. It continued to be used until 1760, but shortly after the arrival of Fr O’Brien, part of the building collapsed.133 It was obvious to Fr O’Brien that the barn-like chapel was deeply unsuitable for divine worship, so he set about building a proper church. He acquired a tract of land from Harmood W...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction

- One The Monastery of St Finbarr

- Two St Finbarr’s Abbey Refounded and Norman Beginnings

- Three From Norman Beginnings to the Reformation

- Four Suppression and Resurrection

- Five The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

- Six The Established and Dissenting Faiths

- Seven Twentieth-Century Churches

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Copyright