![]()

CHAPTER 1

Atrophy of an Army

INTERWAR HISTORY

1918–39

At the beginning of 1919 the forces of Germany lay defeated, and those of Britain and her allies were strong and all-conquering. But by 1939 Britain’s army was small, ill equipped and ill trained, while Germany’s army was vigorous, well equipped and about to be triumphant. Why such a reversal? The answers lie largely in the terms imposed on Germany in 1919, and the national attitudes and reactions of Britain and Germany in response to international events as they unfolded.

This chapter reviews briefly the main historical events from 1919 to 1939, beginning with the features of the Treaty of Versailles that set those events in train. The reactions of progressive British governments are then considered, leading on to the effect those reactions were to have on the state of the British Army in 1939.

The Treaty of Versailles was the formal instrument for ending the hostilities of the First World War. Most countries who fought against Germany were invited; the significant countries not invited were Germany and Russia. There were three people of outstanding importance at the conference to determine the terms of the treaty: France’s Georges Clemenceau, known as Le Tigre (the tiger), who stood for an earnest desire to fetter and cripple Germany forever; America’s Woodrow Wilson who was full of ideas (his Fourteen Points) but no plan; and Britain’s Lloyd-George who felt initially that Germany should be treated with justice and compassion, but his self-serving political instincts, and an imminent election, made him change his view and promise that he would ask for the trial of Kaiser Wilhelm II, punishment of those responsible for atrocities, and the fullest indemnities for Germany.

With one main leader withdrawn into the clouds and the other two bent on hammering Germany it is hardly surprising that the terms of the treaty (see Appendix I) were considered by Germans at the time, and by historians subsequently, to have been unreasonably harsh. Like any other proud nation Germany was not going to take these perceived injustices lying down. There was a mood which would compel them, under a suitable leader, to right these wrongs.

In contrast to this determined attitude the British wanted only to sit back peacefully and not have to be involved in a similar conflict ever again. They would look after the empire, of course, but the League of Nations would look after any international unpleasantness.

SIGNIFICANT HISTORICAL EVENTS LEADING TO THE OUTBREAK OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR:

3 January 1925: | Mussolini becomes dictator of Italy |

October 1929: | Wall Street Crash |

18 September 1931: | Japan invades Manchuria; League of Nations does nothing |

2 August 1934: | Hitler becomes dictator of Germany |

3 October 1935: | Mussolini invades Abyssinia |

7 March 1936: | Hilter reoccupies Rhineland |

12 March 1938: | Hitler invades Austria |

August/September 1938: | Czechoslovakia under pressure of invasion; war seems inevitable |

September 1938: | Chamberlain meets Hitler and finally gets his ‘letter of intent’ (so-called ‘peace in our time’) |

15 March 1939: | Hitler invades Czechoslovakia and occupies Prague |

31 March 1939: | Chamberlain promises aid to Poland in the event of aggression |

23 August 1939: | Germany and Russia sign a non-aggression pact |

1 September 1939: | Germany invades Poland |

3 September 1939: | Britain and France declare war on Germany |

BRITAIN’S DEFENCE NEEDS

A nation’s survival can be defended and upheld by three main means: diplomacy, economic strength and armed strength. During the period 1919–39 these methods were used to achieve the objective of Britain’s national survival, and in the early part the main thrust was by diplomatic and political means. Britain, along with many other countries, considered that the League of Nations would provide collective security for all member nations – and, indeed, all the world. It was therefore considered that the need for armed strength as a complement to diplomacy was of secondary importance. Indeed, soon after the end of the First World War the government promulgated the policy called the Ten Year Rule. This stated that in the government’s view there was no likelihood of a war for ten years, which clearly meant that there was no need to keep substantial armed forces in being during those ten years. In 1920 it was assumed that there would be no war until 1930; in 1921 no war until 1931; and so on. Thus the provision of armed forces was allowed to slip back by a process of progressive procrastination.

Britain’s defence requirements were more complicated than those of many other countries because she had to consider not only the defence of the home islands, but also that of her imperial possessions. This defence was required not only for those possessions themselves but also because they provided much of the raw material and food that Britain required. It was necessary not only to protect those countries themselves from external or internal threats but also to protect the sea lanes between those countries and Britain. A particularly important locality that required protection was the Suez Canal, forming as it did a vital link between Britain and India and other British possessions beyond Suez. So to the first requirement for the employment of armed strength, home defence, was added the second, maintaining imperial holdings and communications.

The third area where armed forces might have to be employed was what was called the Continental Force. This requirement was for an armed force which could go to the aid of Britain’s allies, specifically those on the European continent. This had been done in 1914 when Britain sent the expeditionary force to help the French and Belgians, which over a four-year period became a very substantial army. There was much debate as to whether Britain still required to maintain the capability of sending such a force. This debate was renewed from time to time during the course of the 1920s and the 1930s.

METHODS FOR ACHIEVING DEFENCE OBJECTIVES

Assuming that the three main defence objectives are home defence, protection of imperial holdings and the communications with them, and the provision of a continental force, what are the ways in which those objectives can be achieved, and what are the requirements for the Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force (RAF) respectively?

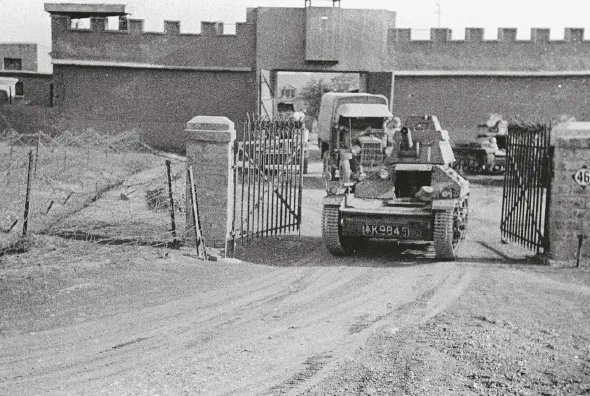

A Light Tank Mk VI B (Indian pattern) leaves a fort at some point in the mid-1930s. (Tank Museum 1623/B6)

A Light Tank Mk VI B (Indian pattern) ascends – with difficulty – the Nahakki Pass; the light tanks could at least move in such country, and there was therefore a significant demand for this type of tank. (Tank Museum 268/A4)

Home defence depends on all three services, in particular the Royal Navy, to prevent any forces landing on Britain’s shores. That task can also be undertaken by the RAF who can intercept aircraft supporting invasion forces; the RAF can also repel those invasion forces themselves. The British Army assists in preventing hostile forces from landing, and then has the major role in combating those forces once they have landed; another role is the provision of anti-aircraft defence.

Imperial holdings and communications needed to be protected particularly by the Royal Navy because of the Navy’s great mobility and ability to move quickly from one trouble-spot to another with substantial firepower. The role of the RAF in defending imperial holdings and communications was to assist the Navy and to carry out bombing and other attacks on insurrections within the countries which form part of the empire. The role of the Army was to provide a force which could defend the countries of the empire against invasion and against internal insurrection or other troubles. In some countries, particularly India, the troops from Britain were very substantially supported by troops of the country itself, but there was still a need for British forces in various roles in all of those imperial possessions.

The Continental Force was a much more contentious item. Basically the requirement was to provide support to Britain’s European allies. Britain provided substantial forces in the First World War and gave great support to the French. If Britain were allied to France at any future time would France expect a contribution from Britain in her defence? The answer was obviously yes. But what form could that support take? One view put forward very strongly was that the most effective form of support would be by an air force, and a land force would not be necessary.

The role of air forces was a subject for intense debate after 1918. Their expansion during the First World War had been very substantial considering that, in effect, there were no air forces at the beginning of that war. By the end Germany had 200 squadrons of aircraft, France 260 and Britain 100. These forces were mainly used as fighter squadrons or for reconnaissance. There was certainly some bombing, and the bombing which took place over England created a very strong impact on both the people who were bombed and the British government. It was felt that bombing alone could destroy both the will and the capability of a country to defend itself. This was put forward in particular by an Italian, Giulio Douhet, in his book The Command of the Air (1921). His thesis was that there was no effective defence against the bomber and that both civilian morale and industrial and defence installations would be destroyed very quickly after the employment of substantial air power.

This then presented the government with two major choices for providing support to a continental ally. The first was by building up a substantial bomber fleet, the second by providing a substantial armed force on the ground. In both cases the Royal Navy would provide support, particularly to the armed force on the ground. There was at that time a reluctance on the part of the RAF to provide air support, both in protection of supply routes to the Army and in a direct tactical fashion.

BRITISH GOVERNMENT REACTIONS TO THE EVENTS, 1918–39

In this section we consider the reactions of the British government to the historical events which occurred between 1920 and 1939, and consider in particular the actions that were taken to maintain the defence objectives mentioned in the previous section.

The first significant action to be taken was obviously to demobilize all the enormous forces that Britain had raised during the First World War. Because it seemed clear that this had been ‘a war to end wars’ it was not necessary to consider the need to fight another war for a long time. Some people thought that there would be no more wars. The decision regarding no more wars resulted in the Ten Year Rule mentioned in the previous section. Ministers could assume that there would be no serious assault on Britain itself, nor would there be any need for the Continental Force. The only requirement that had to be met was that to defend the imperial p...