![]()

Part 1

THE BEAT OF DRUMS

by Oliver Lindsay

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Beat of Drums

Hong Kong, Saturday 6th December 1941. The day of bright sunshine started no differently from any other relaxed weekend in the Colony’s long history. Yet it turned out to be a day nobody there would ever forget.

The newly arrived Governor, Sir Mark Young, attended a fête at Christ Church in Waterloo Road. Happy Valley racecourse was crowded, as usual. The Middlesex Regiment played South China Athletic at football. In the evening at the massive Peninsula Hotel in Kowloon both ballrooms were packed for the ‘Tin Hat Ball’ which hoped to raise the last £160,000 to purchase a bomber squadron which the people of Hong Kong planned to present to Britain.

It could have been a typical weekend – but on that same day, following secret instructions from Tokyo, a large number of Japanese civilians left the Colony, most of them by boat to Macao and then on to Canton.

* * * * *

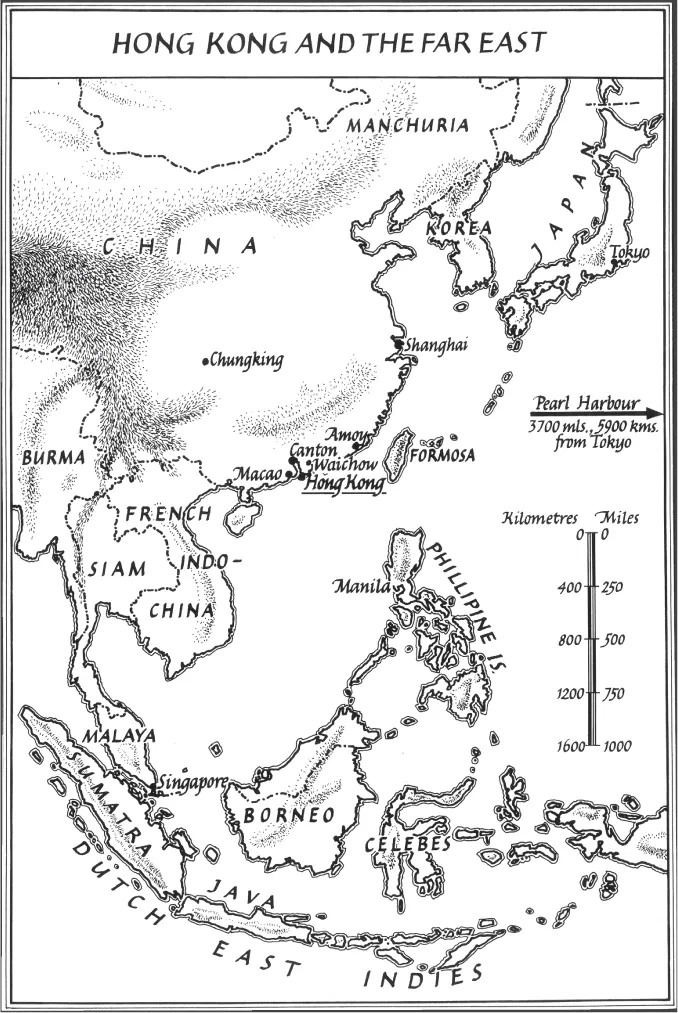

Some 3,700 miles to the east of Tokyo, Japanese midget submarines planned their approach to eight battleships of the American Pacific Fleet at anchor at Pearl Harbor. Beyond them lay another 86 American ships. The American aircraft nearby, and also in the Philippines southwest of Hong Kong, “were all tightly bunched together, wing tip to wing tip, for security against saboteurs,”1 despite orders to disperse them.

Some four weeks earlier, on 5th November 1941, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the C-in-C Combined Fleet, was warned by Imperial Japanese Headquarters that war was feared to be unavoidable.

General Douglas MacArthur in Manila remained convinced that there would be no Japanese attack before the Spring of 1942. As the commander of the American and Filipino troops in the Philippines, and a man of immense prestige, few contradicted him.

The Japanese regarded the Philippines as a “pistol aimed at Japan’s heart”. An intercepted coded message from Emperor Hirohito’s Foreign Office to the Japanese Embassy in Berlin referred to breaking “asunder this ever strengthening chain of encirclement which is being woven under the guidance of and with the participation of England and the United States, acting like a cunning dragon seemingly asleep”. This was a surprising and rather silly claim because the Japanese had already seized every port on the Chinese coast except Hong Kong.

On 27th November the US Navy Department sent out a message which began most ominously. “This despatch is to be considered a war warning… an aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days… the number and equipment of Japanese troops and the organization of naval task forces indicates an amphibious expedition against either the Philippines, Thai or Kra Peninsula, or possibly Borneo.”2

J C Grew, the US Ambassador in Tokyo, believed that the Japanese negotiations with the Americans in Washington were “a blind to conceal war preparations”. He warned his Government that Japanese attacks might come with dramatic and dangerous suddenness. The Ambassador’s estimate of the situation was confirmed by intercepted secret messages from Tokyo to Washington; they stressed the urgency of bringing the negotiations to a favourable conclusion by 29th November since “after that [date] things are automatically going to happen”. Roosevelt gloomily concluded that America was likely to be attacked within a week.

On 29th November British, American and Dutch air reconnaissance was instituted over the China Sea; Malayan defences were brought to a higher state of readiness. The Japanese had earlier received intelligence of the arrival of the Prince of Wales and Repulse in the Far East.

All Japanese forces were notified on 1st December that the decision had been made to declare war on the United States, the British Empire and the Netherlands.

Four days later Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, the Commander in Chief of Britain’s Eastern Fleet, flew back to Singapore from Manila after conferring with MacArthur and Admiral Tom Hart, MacArthur’s naval counterpart. Phillips, who had four days to live, left empty-handed; the Americans could spare neither men nor weapons.

Hong Kong and the Far East

That weekend Churchill was at Chequers with Averell Harriman. He was President Roosevelt’s ‘defence expediter’ in England, who later became the American Ambassador in Moscow and then London. They discussed the progress of the Germans on the Russian front, while awaiting news of the British forces in Libya. But the difficulty of discovering Japanese intentions was to the forefront of their minds.

Meanwhile on 6th December President Roosevelt in Washington started drafting a personal appeal to Hirohito in a final attempt to avoid war. George Marshall, the US Army’s Chief of Staff and senior general, prepared a dispatch to MacArthur with a final warning that war seemed imminent. His vital information subsequently went astray; radio communication with the Pacific broke down the next day.

Marshall’s opposite number in London, General Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, had been in post six days. Brooke that same day was enjoying his first quiet morning, hoping to slip home to his family later that afternoon. “However, just as I was getting ready to leave, a cablegram from Singapore came in with news of two convoys of Japanese transports, escorted by cruisers and destroyers, southwest of Saigon moving west,” he wrote in his diary. “As a result the First Sea Lord at once called a meeting of Chiefs of Staff.” They examined the situation carefully but, understandably, could not decide whether the armada was sailing towards Siam (Thailand), Malaya or “whether they were just cruising around as a bluff. PM called up from Chequers to have results of our meeting phoned through to him.” A second message came from Singapore shortly afterwards. “It only said that the convoy had been lost and could not be picked up again.”3

At 7.20 p.m. Singapore sent an immediate signal to the Royal Air Force in Hong Kong ordering them to adopt “No. 1 degree of readiness”. Wing Commander H G Sullivan, who had arrived in Hong Kong six days earlier, gazed at the signal with dismay for he had nowhere to conceal his three obsolete Vildebeeste torpedo bombers and two Walrus amphibians. All of them were over ten years old with a maximum speed of 100 mph. “It had been suggested that dispersal bays be carved out of the hills, but like everything else in Hong Kong these did not materialize,” he later reported.4 The RAF aircraft remained at Kai Tak airport.

That evening Major G E Grey 2/14 Punjabis, who was commanding the troops on Hong Kong’s mainland frontier, “received a police message stating that three Japanese Divisions (38,000 men) had arrived at To Kat, eight miles from the frontier on the previous evening”, recorded the second entry in Hong Kong’s War Diary.5

Major General C M Maltby, the recently arrived General Officer Commanding British forces in the Colony, wondered whether the report was nonsense or if he should mobilise the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, order all his 12,000 troops to their battle stations and start activating the demolition plans. Should he ask the Governor, Sir Mark Young, to summon a meeting of the Defence Council for a lengthy discussion at Government House the following day?

The General’s ADC, Captain Iain MacGregor, was about to be confronted by the Chairman of Hong Kong’s largest and most distinguished bank, who was to arrive fuming at Flagstaff House demanding to see the General. “The Chairman paced the room, all the time telling me the whole thing was bloody nonsense, and that only two days before he had received a coded cable from one of his managers who had been dining the previous evening with the C-in-C of the Japanese Kwantung Army,” MacGregor remembers. The C-in-C had assured the manager that under no circumstances would the Japanese ever attack their old ally, Great Britain. “‘Good God, Iain,’ said the Chairman, ‘you’re a civilian really, a Far East merchant. You know how these Army fellows flap. You know our intelligence is far better than theirs…’”6

General Maltby was not flapping. He was confident that the Royal Scots, Punjabis, Rajputs and Volunteers to the north of Kowloon could hold their defensive positions on the frontier and the Gin Drinkers’ Line for seven days. This would allow sufficient time to complete demolitions of installations on the mainland of value to the enemy. The two newly arrived Canadian Battalions were at Shamshuipo Barracks but they had seen their battle positions, while in the musty, heavily camouflaged pill-boxes on Hong Kong Island, the machine-gun Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment was largely standing-to.

One topic of conversation on that last Saturday of peace in the Far East concerned Duff Cooper, who had been sent by Churchill on a special mission to establish whether the Government could do more about the situation. Cooper, accompanied by his wife, Lady Diana, had met MacArthur before visiting Burma, and then Australia where he met wives evacuated from Hong Kong. Most were demanding to rejoin their husbands in the Colony and he promised them that he would listen to their husbands’ complaints. Fortunately it proved too late to reunite the families in Hong Kong.

One man who had no wish whatsoever to see his wife return from Australia was Major Charles Boxer The Lincolnshire Regiment, Maltby’s senior Intelligence Officer. He infinitely preferred his mistress, Emily Hahn, an American writer who had once been the concubine, it was said, of Sinmay Zau, a frequently impecunious philosopher, publisher and father of a large family. Zau had introduced her to opium and for a time she had become a serious addict; she was also addicted to cigars. She had given birth to a daughter by Charles Boxer in October.

Hahn and Boxer hosted a cocktail party at his flat on that Saturday evening, 6th December. There were no Japanese present, naturally. But Boxer, who had served with the Japanese Army in the 1930s, was regarded by some as being too friendly with them. On the previous day he had enjoyed a lunch with a Japanese General beyond the frontier at which the General had casually asked Boxer whether he could obtain permission for him and his staff to attend a forthcoming race meeting at Happy Valley.7

Major Charles Boxer asked his guests where they would like to dine that night – a smart hotel perhaps, an exclusive restaurant or should they link up with friends at the ‘Tin Hat Ball’ in the prestigious Peninsula Hotel? Yet Boxer was visibly preoccupied; he knew that the massive Japanese armada had been spotted by British reconnaissance aircraft steaming along the coast of French Indo-China (now Vietnam) and that its destination was unknown. He planned to visit the frontier the following day to see what the Japanese were up to. Meanwhile, however, he accompanied Emily Hahn and their guests to a local restaurant for a buffet dinner.

It was just as well that they had not attended the Ball. Towards midnight the orchestra there had just started to play the current favourite, The Best Things in Life are Free, when suddenly the music stopped. T B Wilson, the local president of the American Steamships Line, appeared on a balcony above the dance floor. Urgently waving a megaphone for silence, he shouted, “Any men c...