![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Night Operations 13–14 August 1940

As the Whitleys of 4 Group streamed back from attacking the Fiat factory in Turin and the Caproni works in Milan, the Heinkels He 111H of pathfinder group KGr 100 were returning from their first mission over England where they had bombed the Dunlop works east of Birmingham and the Spitfire factory at Castle Bromwich.

The RAF claimed to have inflicted serious damage on to the Italian factories, where fire and explosions were observed, with hits on railway lines, bridges and a marshalling yard. But with only four bombs apiece the destruction caused by the thirty-two Whitley bombers was hardly significant and the only tangible result of this, and subsequent raids, was to annoy Mussolini to such an extent that a detachment of the Italian Air Force was deployed against Britain towards the end of 1940.

This first RAF attack against the industrial heartland of Italy involved a 1,500-mile flight over the Alps, and it was a great morale booster for the moribund Bomber Command. In addition, the casualties were remarkably light because the Italian defences were so poor. In fact only one plane was hit by enemy fire, but the Whitley was such a robust plane that even on just one good engine it still managed to fly back over the Alps. As it crossed the English Channel and came within sight of the shore, the pilot attempted to land the crippled plane on the beach at Lympe, but the badly buckled aileron finally broke off and Whitley P4965 plunged into the sea taking Pilot Officer Ernest ‘Pip’ Parsons and Sgt Alfred Campion to their deaths. Their bodies were later washed up on the French coast and they are buried at Boulogne’s Eastern Cemetery in the Pas-de-Calais.

The other three crew members managed to extradite themselves from the plane as it sank below the waves, and Sgts Chamberlain and Sharpe were lucky to be rescued by a passing fishing boat. Even luckier was Sgt Marshall who was saved by Peggy Prince who paddled out in her frail canoe when she saw the Whitley hit the water. For this brave action she was awarded the British Empire Medal.

But what of the twenty-one Heinkels He 111H of KGr 100, which had set off from Vannes on their first mission to England? Nine were scheduled to attack the Spitfire factory but only five managed to find the target, and the bomb spread was so wide that fighter production was not seriously disrupted. A ‘Purple’ warning had been received at 22.54 hours and, ten minutes later, five bombers were reported coming in from the south and the searchlights and AA guns went into action as the bombs started to fall. In this first attack nineteen bombs fell on the 60-acre site, with some landing in the fields and on the roads, while a few hit the factory blocks wrecking the buildings and damaging the machinery. The bombs continued to rain down but little further damage was done though eight workers were killed, forty-one were seriously wounded and over 100 suffered minor injuries.

At the Dunlop factory there was even less damage or disruption to output as the bombers again failed to pinpoint their target. A stray bomb did land on the Bromford Tube factory in Birmingham that was producing seamless steel tubes for the War Office, but the plant was not damaged. Though a number of windows were smashed production was not halted. For this elite pathfinder unit this was an inauspicious beginning, and accurate bombing through cloud proved to be a continuing problem.

Approaching the Midlands, powerful beams of light had shot up into the air as the searchlights tried unsuccessfully to cone in on the black-coated planes. A trail of lights and flashes seemed to be tracking their flight path across the night sky. The flak was heavy and though the AA shells were initially bursting away in the distance, they soon closed in on their targets.

Some of the planes were rocked by the nearness of the explosions but they were not knocked off track and they completed their bombing runs without any problems. The He 111s of the 2nd Staffel came in last and, as the flashes of flak faded in the distance and with no sign of any threatening night fighters, they switched to auto-pilot and laid back hoping for an uninterrupted journey home.

They all managed to land safely back at Vannes, returning on a line via Birmingham–Carmarthen–Brest, even though some crews experienced in-flight problems with the auto-pilot and the master compass and, in one unfortunate incident, a signal pistol was fired inside the plane causing burns and blisters to two of the airmen. There were no further reports of any injuries or fatalities but Uffz. Fritz Dorner did not return from the raid. And his aircraft did not reach the target area.

As the He 111H (6N+HK) flown by Feldwebel Kaufmann made its directional turn towards Swindon, before heading north to the Midlands, there was an almighty thunderclap as a shell exploded alongside sending a shock wave shooting along the whole length of the plane, shaking it from end to end. A shower of sparks from the electrics started a fire in the fuselage that the flight mechanic fought frantically to extinguish. The aircraft then started to roll alarmingly from side to side and, out of control, it slid into a shallow dive. Kaufmann fought desperately to right the plane but there was no response from the controls, and he gave the order for the crew to abandon their crippled machine.

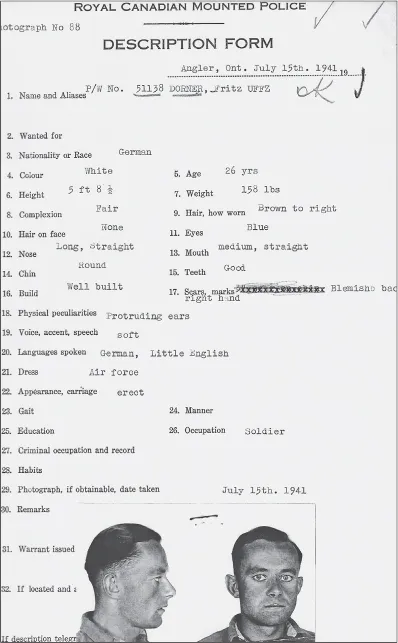

Uffz. Freidrich ‘Fritz’ Dorner

The pilot sat in an all-in-one parachute suit but, because of their in-flight duties, such an outfit was impracticable for the rest of the crew. Instead, over their flying suits they wore a harness into which the parachute had to be manhandled into place. The wireless operator Fritz Dorner was the first to clip on his parachute and, with a quick farewell, he baled out into the darkness.

Yet, as the remainder of the crew struggled with their parachute harnesses the plane remarkably righted itself and, as it levelled off, Kaufmann, with the aid of the flight mechanic, regained control of the shattered machine and, after a quick check, was satisfied it was still flyable. But to continue with the mission, with the plane in such a perilous state, would be foolhardy and he gently pointed the bomber back towards the Channel and home, even though without the radio operator it would be a hazardous return journey. As he nursed the battered bomber back to base he pondered on how he was going to explain the absence of one of his crew to his commanding officer.

As he floated down, Fritz peered into the gloom hoping to catch a glimpse of the white parachutes of the rest of the crew but, no matter how hard he looked, there was no sign of them. So intent was he in scanning the night sky that he didn’t realise how fast the ground was rushing up towards him and, by not bracing himself, he landed heavily, badly injuring his left leg. He came down in a grass field near some farm buildings on the outskirts of the small town of Balcombe, but despite the debilitating injury he managed to haul himself towards a farmhouse that he could see in the distance. Knocking on the door he fell into the hall as it opened and, looking up at the startled the farmer, he uttered the words he had rehearsed, ‘I have come from the air, can you help me?’ The farmer helped him into the house and made him comfortable. The police were soon on the scene and, when the military arrived, he was taken to a nearby hospital. Briefly he was interrogated at Cockfosters but they didn’t discover that he was a trained instructor in the X-Verfahren blind-bombing system and he was soon packed off to a POW camp. By the summer of 1941 he was languishing in Camp Angler in Canada where he sat out the rest of the war.

‘Fritz’ Dorner (second left, front row) with fellow POWs at Camp Angler. (Photograph: Friedrich Dorner)

Fritz had joined the Luftwaffe on 1 November 1935 and, after qualifying as a radio operator, he became an instructor before joining KGr 100 in February 1939 where he received intensive training at Wurzburg on the operation of the then secret X-Verfahren system. His flying book shows that these in-flight training sessions were undertaken in a variety of aircraft but mainly in the three-engine Junkers Ju 52 and the excellent, all-metal Focke-Wulf Fw 58. Mysteriously his flying book contains no entries for the three months from September to November 1939, even though he flew combat missions in He 111s during the invasion of Poland. During the attack on Norway, though KGr 100 was heavily engaged, it seems that Fritz stayed out of the action. And during the month of April, once the invasion had started, ten long-distance flights of over 600 miles were undertaken in Ju 52s from their forward base at Konisberg on the shores of the Baltic, which they completed without incident.

During the Blitzkrieg in the West, Fritz was off flying duties during which time the unit had moved back to Germany for its Heinkel He 111s to be re-fitted with the X-Verfahren blind-bombing system, which had been taken out of the plane for the Norwegian campaign. In addition to the W/T mast, the Heinkel He 111s with this equipment now carried two extra radio masts mounted on top of the fuselage and the three were easily recognisable. Promoted to unteroffizier in 1940, he would now be flying with the 2nd Staffel as Feldwebel Kaufmann’s radio operator from the unit’s bases at Kothen and Luneburg, where they would make almost thirty familiarisation flights, concentrating on all aspects of night flying and navigation, before KGr 100 was transferred to France in early August that year in preparation for pathfinder operations over Britain. His stamped logbook shows that he was signed off as an instructor on 10 August. Training was now over. The next flights would be for real.

Their new base was near Vannes, a town of some 30,000 inhabitants on the south-west coast of Brittany, a part of France he had never visited before. With its cafes and restaurants and not too unfriendly locals, it was a reasonable posting and being lodged in a hotel in the centre of the town was something of a bonus, but the airfield facilities were pretty basic. There were no concrete runways and very little maintenance space with only one small hangar and a few wooden buildings, and the planes were therefore kept out in the open where most of the servicing had to be undertaken. Canvas covers were flung over the engines to protect them from the salty sea air but, at best, this was a stop-gap solution because exposing aircraft to the corrosive Atlantic winds was a bad idea.

On 10 August, out of their total operational strength of thirty-nine Heinkel He 111s, only nineteen were serviceable, though this had more to do with the supply of parts than the weather. By 13 August extensive repairs must have been urgently carried out to get the planes up and running because twenty-one were ready for action for the unit’s first major attack on Britain that very night.

Taken by coach to the airfield, Fritz and the rest of the crew were in good spirits when they climbed aboard their plane. As they carried out their pre-flight checks they watched in excited silence as the other aircraft fired up their engines ready for take-off. As the exhausts glowed red it was a colourful and powerful sight as the seven Ketten (chain) of three aircraft lined up and took off in staggered intervals, with their aircraft one of the last to take-off.

Helmut Meyer’s three master Heinkel He 111 of KG 26 shows that it was equipped with the X-Verfahren system. The aircraft was badly damaged prior to the attack on Poland when one of the bombs waiting to be loaded blew up. (Photograph: Helmut Meyer via Geoff Stephens)

Royal Canadian Mountain Police POW record sheet

For Fritz this would be his first and last feindflug or battle flight over Britain, and his plane would be the only one that failed to reach its destination and scatter its bombs over the intended targets. Fritz had no way of knowing, but with their mission abandoned the bombs were probably jettisoned over the Channel – it would have been folly to make a forced landing with a full bomb load. As he fell badly he was just grateful to be alive and, as he shook himself down and limped towards the farmhouse, he started to feel a bit more hopeful and the initial feeling of gloom disappeared with every step. He thought he would not be incarcerated in a POW camp for too long as Britain must soon come to its senses and either surrender or sue for peace. Either way his time as a POW would be short.

The Red Cross would notify his family that he was alive and well and, with luck, he could be home by Christmas though there might be some delay as the ‘Tommies’ were known to be stubborn. Little did he know that he was going to spend the next seven years behind wire, mostly in the snowy wastes of Canada.

He finally made it back home to Thalmassig in 1947, and died in the nearby town of Greding on 9 October 2002, leaving behind a son Friedrich, also known as Fritz, to carry on the family name.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

Messerschmitts over Manston

Early on the morning of 14 August 1940, Hauptmann Walter Rubensdorffer, Commander of Erprobungsgruppe 210, dispatched all serviceable aircraft from their home airfield at Denain to Calais-Mark, the forward base from which all their operations against England were now being launched. The only mission listed for that day was a lightning, low-level attack against Ramsgate and Manston aerodromes.

The 2nd and 3rd Staffels, equipped with Messerschmitt Me 110 Zerstorers, set off first for the short 25-minute flight at about 7.00 hours with the Me 109s of 1st Staffel – under the command of Oberleutnant Otto Hintze – taking-off slightly later, landing at Calais-Mark at 07.45 hours. The planes were then refuelled and made ready for action but, for some reason, Hintze’s pilots would not be thrown into the fray and remained inactive all day before flying back to Denain at 18.20 hours.

An experimental unit, Erprobungsgruppe 210 had only been formed some six weeks earlier, primarily to evaluate the dive-bombing capabilities of the Luftwaffe’s front-l...