![]()

Six

GROWTH AND CHANGE 1800 TO 1900

The 19th century in Banbury was a time of growth and change. Traditional market town activities persisted and livestock continued to wander the streets but this was against a background of industrialisation and town expansion. At the beginning of the century the town was still governed according to the charter of 1718 but a series of Acts of Parliament abolished the Corporation and curbed the powers of the Justices, replacing them with a system of government more representative of the population, or at least of the property owners.

The first improvement in the management of Banbury’s affairs depended on the private 1825 Act for ‘Paving, Cleansing, Lighting, watching and otherwise improving the several streets, lands, public passages and places in the Borough’. By the terms of this Act, 40 local commissioners were empowered to carry out the role of a town council. They had responsibility for road repair, paving of footpaths, repair and erection of pumps, control of the borough stretches of turnpikes and the power to ensure that property owners drained their premises properly. Lighting was a concern of theirs and this meant oil lamps prior to the formation of the Banbury Gaslight and Coke Company in 1833. The Corporation and the commissioners were frequently at odds, especially on the issue of the erection of buildings.

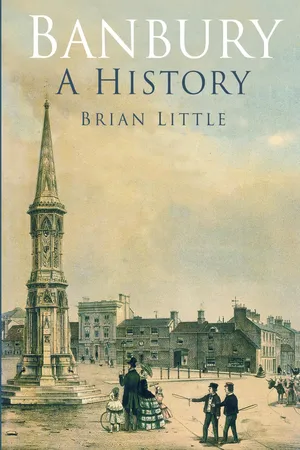

52 The Davis map of Banbury 1825.

53 Formation of the Gaslight and Coke Company presaged the transition from oil to gas lamps.

Although both bodies were responsible for policing, Banbury was often an unsafe environment because of the inefficient supervision of the watchmen, who failed to check the growth in robberies and cases of assault at the 12 annual fairs. To make matters worse, Neithrop was outside the scope of the watch and was rightly regarded as a disorderly suburb. In 1826 a mob uprooted trees which had been planted on the Green as part of an improvement scheme.

Reform measures of the 1830s brought considerable change to the pattern of local government countrywide. The Reform Bill of 1832 ended the Corporation’s right to elect the borough Member of Parliament, and the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 replaced it with a town council elected by ratepayers of the borough. The new council was to consist of 12 members, 4 aldermen and an annually elected mayor. When the first election took place on Boxing Day 1835, only 148 out of a possible 275 voters bothered to go to the poll. The outcome was decisive: 12 candidates each received over 100 votes whilst the remainder scored 11 or less.

The first members of Banbury Council |

Timothy Rhodes Cobb | Banker | 147 |

James Wake Golby | Attorney | 145 |

Thomas Tims | Attorney | 144 |

John Munton | Attorney | 144 |

Thomas Golby | Carrier | 144 |

John Hadland | | 142 |

Lyne Spurrett | Ironmonger | 141 |

William Potts | Newspaper Proprietor | 140 |

Thomas Gardner | Grocer | 139 |

Richard Grimbley | Wine Dealer | 138 |

James Hill | Builder | 138 |

John Wise | Doctor | 136 |

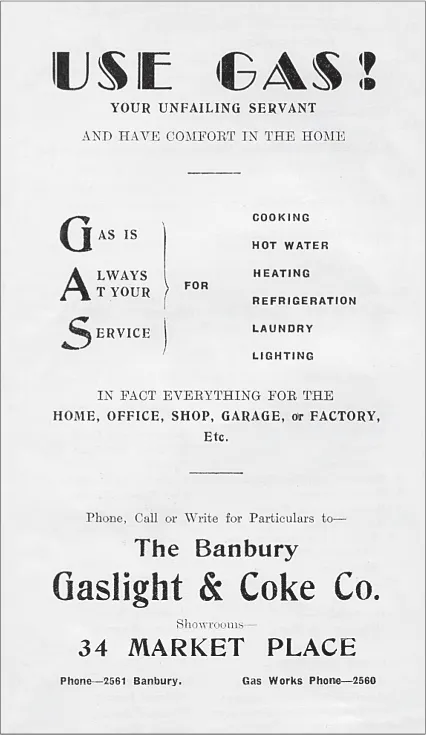

The terms of the 1835 Act meant that only Banbury came under the control of the new council. Hamlets like Grimsbury and Neithrop were excluded and did not even benefit from the formation of a police force in 1836. Neithrop attempted to remedy this the lack by setting up the ‘Neithrop Association for the Prosecution of Felons and other offenders’. Those who became members did so because they wanted protection for themselves and their property.

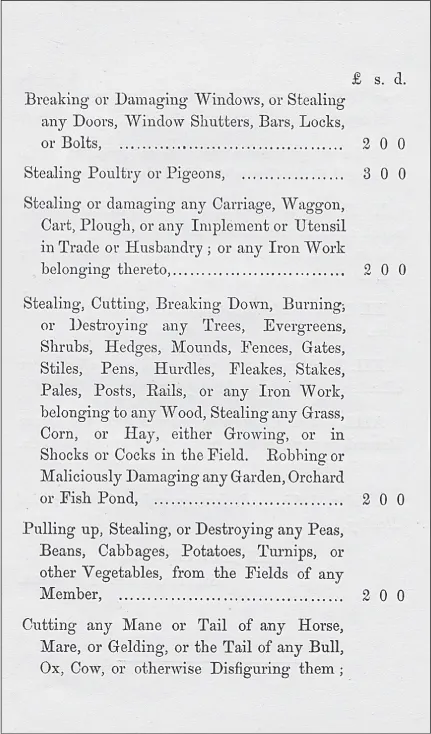

54 Title page of an original pamphlet of the Felons’ Association 1875.

One of the areas of council responsibility that proved to be increasingly unsatisfactory was the town gaol. Between 1836 and 1852, when the gaol in the Market Place closed, the building was regarded as old and inadequate. And anyone committed for trial in Neithrop was taken to Oxford. In March 1851 the council considered a plan for a new gaol devised by Mr Walker, the current gaoler. A sub-committee appointed to consider it subsequently gave approval to the scheme, and the drawings were shown to Henry Underwood, an Oxford architect, who quoted £50 for preparation of plans and a basic sum of £3,800 for the construction. It was as well the council was taking this action because in April 1851 the Inspector of Prisons reported that he had not seen a gaol so bad.

55 Extract from the list of rewards offered by the Association.

Banbury Guardian reports of the time identify the proposed site as Parr’s Piece in Calthorpe, which was beyond the borough boundary and in the ownership to the Rev. Risley, but the location caused a great split of opinion. By May, other possible sites under consideration included Calthorpe Lane, Cornhill, Back Lane, Bridge Street and South Bar Street. A Mr Davies offered some land in the last of these areas, and Thomas Rhodes Cobb indicated his willingness for the site of the old workhouse to be used.

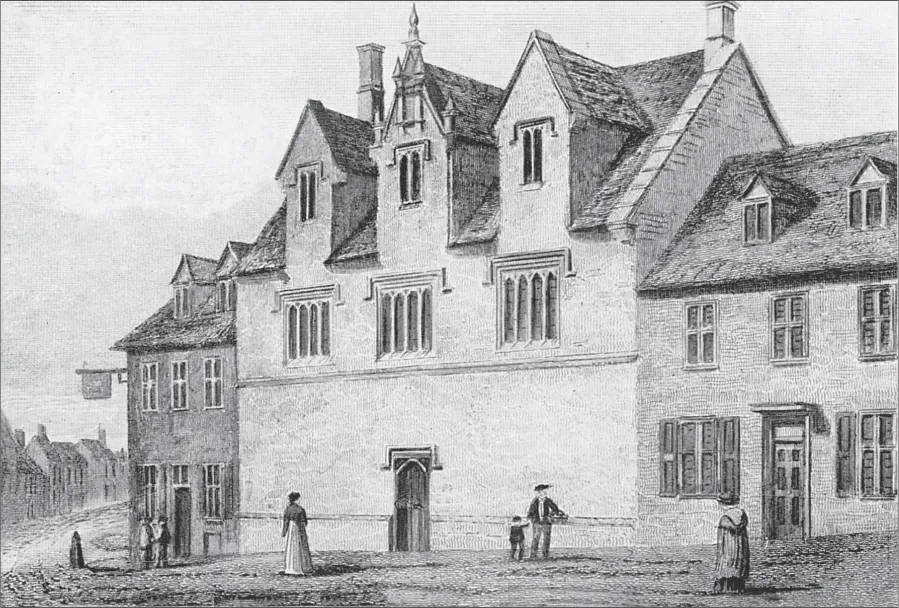

56 The Old Gaol in Banbury Market Place was built in 1646 and remained in use as a prison until 1852. In the late 17th century the rooms above the cells were used as the Staple Hall for the town’s wool trade, and from 1705 until 1817 the Blue Coat School was held there.

In 1852 the various proposals for a new prison were abandoned and the old gaol closed; the remaining prisoners were sent to Oxford. The funds reserved for the construction of the new prison were transferred to the new Town Hall, which duly opened in October 1854.

The canal extension from Coventry and its subsequent continuation to Oxford resulted in boat-related families basing themselves in Mill Lane, Factory Street and Cherwell Streets. These were highly mobile people as evidenced by a survey entry for 8 Cross Cherwell Street that referred to unnamed inhabitants as having ‘gone boating’. The commercial value of the Oxford Canal, with its link to the port of London by way of the Thames Navigation, is very well illustrated in a series of letters written to a Mr Hartall of Shutford. In November 1815 John Williams of West Smithfield in London dispatched three chests of yellow soap to Paddington Wharf where they were collected by Pickfords, who had a regular fly boat service to Banbury. Thirteen years later Mr Hartall was still buying his soap from Williams, then of Clerkenwell. A letter dated 28 August 1828 indicates a £27 14s. 2d. cost for chests of soap and the expense of transportation by, as before, the firm of Pickfords, who called at the Old Wharf in Banbury on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays according to Rusher’s 1828 List.1

In all probability cargoes such as the yellow soap would have continued their journey to Shutford by means of the village carrier’s cart. The carriers collected items of shopping for village customers, conveyed passengers for a small fee and transported goods for Banbury businesses throughout the 19th century. The thirty or so carriers named in Rusher’s List of 1799 had grown to 208 carriers paying 465 visits to the town per week by 1838. They all developed good relations with local inns such as the Leathern Bottle and the Old George, whose yards received horses so that they could be fed and watered.

In the first half of the century passengers for other parts of the country relied on coaches and post-chaises. Advertisements in the Banbury Guardian illustrate the importance of the town to stage-coach travel. The appropriately named Comet ran by night. It left Leamington Spa at 5 p.m. and halted at the White Lion in Banbury’s High Street at 9 p.m. It pursued its long and often chilly journey to the King’s Arms in London’s Holborn, arriving there at 9 o’clock the following morning. In 1838 a coach-railway service was established. The same Banbury inn was used by the Royal Mail coach that departed the town at 7 o’clock each morning and linked up with the Great Western Railway service operating from Wolverhampton to Paddington at Wolverton station at 10.30 a.m. The coach returned from Wolverton at 2.15 p.m. and reached Banbury at 5.30 p.m. thus allowing the journey to be made in the d...