- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

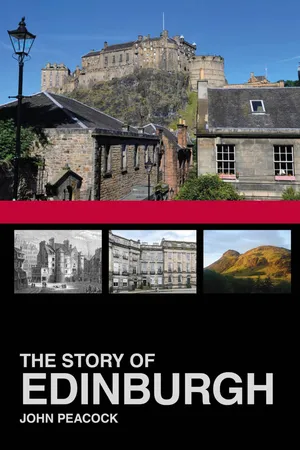

The Story of Edinburgh

About this book

This richly illustrated history explores every aspect of life in Edinburgh. This book covers the history of the city of Edinburgh from the first Mesolithic explorers who camped on the shores of the Forth some 10, 000 years ago to the controversies of modern times. Taking a wider perspective it explores the ever-changing world resulting from industrialisation, which brought immigrants, wealth and poverty. Following that, new methods of transport opened up Edinburgh to the wider world. Now, with its historic architecture the city can become a battleground between developers and motorists who want more space in the central areas and conservationists who wish to protect the city's landscape.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Story of Edinburgh by John Peacock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

EDWARDIAN EDINBURGH AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Edwardian Edinburgh

Prince’s Street

Three large stores – Renton Ltd, Jenner’s and Cranston & Elliot – were now situated near the east end of Prince’s Street. John Wright & Co. occupied Nos 104, 105 and 106, where they sold millinery and ladies’ clothing. Forsyth’s opened their new store in 1907; this shop also specialised in tartans and handknitted Shetland goods. A large store at the western end of the street was owned by Robert Maule & Co.

The demand for personal photographs continued with eight studios, mainly in the centre of Prince’s Street – at this time, few people owned their own cameras. Many jewellers, goldsmiths and watchmakers had gravitated towards the street, attracting the custom of wealthy clients. Some of the leading political groups of the time had clubs and offices here and the Scottish Liberal Association’s offices could be found at No. 95 while their rivals, the Liberal Unionists, who opposed Irish Home Rule, were at No. 80. The Scottish Liberals and the Conservatives had clubs for their members close by. (Prior to the First World War, Scotland was dominated by the Liberal Party and even the Unionist split failed to weaken their hold.)

In March 1907 two horses pulling a carriage bolted in Prince’s Street. The police tried to stop the animals but this only led to a constable being injured. Finally, it fell to a cabman to bring them to a stop. Its occupant, Lady Steele, the wife of the lord provost, was shaken but uninjured.

Later in that same month, Thomas Renton, a coachman, dropped Mr MacDonald of Portobello in Castle Street before directing the carriage back to Prince’s Street. The horse slipped and Renton was thrown onto the road. It then wove its way through the traffic on this busy street and down Waterloo Place before a carter stopped it at the Abbeymount. He kindly brought the horse and carriage back to Prince’s Street. The highway was shared by the many horse-drawn vehicles and cable cars; the new motor cars were just making their appearance.

One of the biggest cultural influences in the twentieth century began during its first decade. The new ‘picture palaces’ brought early moving pictures to the public. The Prince’s Cinema opened at No. 131 Prince’s Street a few years before the war broke out.

Following the drop in tourist numbers in 1909, the state of West Prince’s Street Gardens was brought up. It was claimed that it had become ‘a loafer’s paradise’. Parents would no longer permit their children to use the gardens and ‘visitors making their way forward through such a squalid mob must consider what sort of citizens the Scottish capital rears’, reported the Evening News in August 1909.

A Shooting in Elm Row

In March 1901 John Hume, a 30-year-old joiner, entered the baker’s shop of John Smith & Son in Elm Row. He pulled out a revolver and fired at Catherine Grant, one of the young shop assistants. Fortunately, she ducked, but more shots followed. However, ‘Hume’s aim was as bad as his intentions and none of the shots took effect’ (Evening News, March 1901). Colonel Alan Colquhoun, who was in the shop at the time, tried to disarm Hume but received a flesh wound for his trouble. Hume then shot himself and was taken to the infirmary. Later he was charged with assault using a lethal weapon.

John Hume had previously lodged with Catherine Grant’s father and had developed a ‘liking’ for the 17-year-old girl. A plea of insanity was rejected as Sir Henry Littlejohn had found him quite sober and rational. Hume was sentenced to twelve years in prison.

Robert and Walter Pattison

The firm of Pattison Ltd, spirit merchants, were declared bankrupt in 1898, but questions began to be asked about the business methods of the two brothers. It took another three years before the evidence collected led to prosecutions. The Evening News commented, ‘Great surprise is expressed in commercial circles at the long delay that took place before the Crown Authorities took steps to affect the arrests.’ The brothers were charged with false accounting – overstating the company’s profits.

They had also borrowed over £39,000 from the Clydesdale Bank. This was a loan taken by the company which was then appropriated by the brothers for their own use. One of the scams they had set up in a warehouse (probably in Constitution Street, Leith) involved the purchase of cheap Irish whisky at 11½d a gallon. Some Scotch was added and the barrels were labelled ‘fine Old Glenlivet’ – worth 8s 6d a gallon! It was never put on the market. Robert Pattison was found guilty on all four charges and sentenced to eighteen months, while his brother, found guilty on only two charges, received nine months. Quite a few observers (and no doubt creditors) were astonished at the leniency of the sentences given by Lord McLaren.

The Stockbridge Explosion

In 1860 the Tod Brothers, flour millers in Leith, acquired the Stockbridge Mill. During the middle of the 1890s they purchased a gas engine to run the machinery of the mill and in 1901 the company decided to replace this with a new electric one. Messrs Stewarts of Bonnington bought the old machine and sent five of their men to Stockbridge to remove this old gas engine.

The mill complex included a building on the street which contained three shops on the ground floor. Above these were the mill offices and storerooms. The gas engine was in the yard behind this building. It is believed that the men failed to turn the gas completely off, and the explosion which followed killed all five men, as well as James Thomson, the mill manager. Others were injured and the mill itself damaged in the resulting fire. Mr Bowie, a grocer and wine merchant, had practically the whole contents of his shop blown into the street, and ‘A tin of meat made a very clean looking hole in a shop window opposite’.

One tenement literally had a window blown in. The two ladies occupying a flat discovered a ‘heavy window frame blown right into the middle of the room’. They had escaped without injury, not being in that room at the time.

The Great Storm, November 1901

The revenue cutter Active lay 1½ miles off Granton. In the high winds the ship dragged her anchors, leaving her to be driven onto the East Breakwater of the harbour. She then broke up and sank. Only three of the twenty-three crew on board at the time survived the disaster. The Swedish ship Bele pulled two men out of the water and the third man was found by one of the porters wandering round the harbour.

Four yachts in Granton were also sunk by the storm, leaving only their masts to peer above the water. Signal and telegraph lines collapsed in the high winds, disrupting railway traffic.

Hardship for the Poor

The first months of 1905 brought considerable distress to the poor of the city. The lord provost, Sir Robert Cranston, and some of the leading citizens set out to help those suffering hardship with the aid of the Evening News’ Shilling Fund. The Corn Exchange in the Grassmarket became the main feeding station. Other soup kitchens were set up in Causewayside, Greenside, Stockbridge, Gorgie and the Canongate. The army provided cooks and even town councillors lent a hand, as reported in the Evening News in January 1905:

There was something of humour and pathos in seeing a town councillor unbending to a tiny youngster while he handed over a bowl of soup with the gentle admonition, ‘mind your fingers, my dear, it’s rather hot’.

Another supporter of this work was Mr H.E. Moss of the Empire Theatre who donated £50 to the Shilling Fund. At the first opening of these soup kitchens on Monday, 9 January, food was prepared for 800–900 people, but even that was not enough. Sir Robert Cranston personally handed out the soup and bread. An observer commented in the Evening News of January 1905, ‘Destitution was written hard on almost every face and there was ample evidence of the great need there is for such a scheme as was inaugurated today.’

Reverend Aitken Clark of the Cairns Memorial Church in Gorgie led the effort in that district. This soup kitchen fed sixty-three families comprising 200 individuals. ‘There is more genuine distress among the artisan class than during my nine years work in the city,’ he told a reporter.

The town council set up a job creation scheme employing an extra 1,182 men in various departments. This was later estimated to have cost £5,000–6,000. The Shilling Fund gave Provost Mackie in Leith £25 to aid his relief work in the port.

Flora Clift Stevenson

Flora Stevenson was born in 1839, the youngest of eleven children. Her father, James Stevenson, was a partner in the Jarrow Chemical Company. On his retirement James set up home in Edinburgh with some of his children. The 1872 Act setting up school boards gave an opportunity for women to take an active role in public service and Henry Kingsley persuaded Flora to stand as a candidate. In 1873 she was duly elected as a member of the Edinburgh School Board, a position which she held until her death in 1905.

Flora, like her sister Louisa, wished to improve the educational opportunities for women. Louisa Stevenson, who served on St Cuthbert’s Parish Council, worked tirelessly to improve access for women into higher education. In 1894 she opened a residency for women students in George Square. The University of Edinburgh awarded her an honorary LLD in recognition of her work in this field. Sir Ludovic Grant commented, ‘It was fitting that one who was so instrumental in bringing university degrees within the reach of women should herself receive our highest degree.’ Louisa died in 1908.

Flora Stevenson became convenor (chairman) of the attendance committee, responsible for prosecuting parents who refused to send their children to school. She proposed the idea of setting up a day industrial school to deal with this problem. However, it took some fifteen years before Parliament passed an Act allowing the school boards to carry this through.

Many children from poor families lacked proper clothing and food and Flora joined the Committee to Aid Destitute Children, set up in 1883. With the support of the C...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- One: Edinburgh During the Prehistoric Era

- Two: The First Millennium

- Three: The House of Canmore

- Four: Edinburgh in the Years 1296–1399

- Five: Edinburgh During the Fifteenth Century

- Six: The Early Sixteenth Century

- Seven: The Reformation

- Eight: The Reign of James VI

- Nine: Charles I and the Commonwealth

- Ten: Restoration and Revolution

- Eleven: The Early Eighteenth Century

- Twelve: The Late Eighteenth Century

- Thirteen: The Growing City, 1800–40

- Fourteen: Early Victorian Edinburgh

- Fifteen: Late Victorian Edinburgh, 1870–1901

- Sixteen: The Old Town

- Seventeen: The New Town

- Eighteen: Edwardian Edinburgh and the First World War

- Nineteen: The Inter-War Years, 1918–39

- Twenty: The Second World War

- Twenty-one: Post-War Edinburgh, 1945–59

- Twenty-two: The Last Decades of the Twentieth Century and Beyond

- References

- About the Author